Adventure! Darwin and Climate Change in the South Atlantic

At the risk of asking a somewhat grandiose question, will we be able to adapt to climate change, or alternatively face extinction? If he were alive today, it’s a question which might have vexed Charles Darwin — though the naturalist would not have denied environmental change, the colossal pace of global warming would have undoubtedly startled him. It’s also a question which recently concerned me while participating in an expedition in the south Atlantic. Fittingly titled Darwin 200 Initiative, the voyage seeks to retrace the scientist’s travels. From 1832-1835, Darwin made his way through South America aboard HMS Beagle, during which time he made key observations pertaining to wildlife which would later inform the theory of evolution.

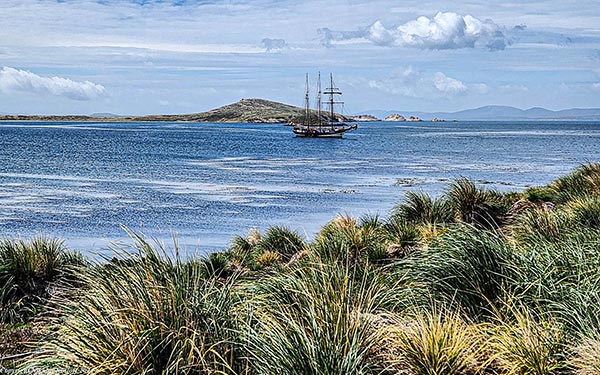

Never having participated in a sailing expedition, much less an expedition on choppy south Atlantic seas, I wasn’t sure what to expect but flew to the Argentine coastal city of Puerto Madryn. There, I boarded Dutch tall ship Oosterschelde, and was welcomed by a multi-national crew of Dutch, Germans, and Danes. Darwin traveled to the nearby Falkland Islands on two occasions, in 1833 and 1834, and his notes dealing with endemic flora and fauna hint at evolutionary thinking relating to subsequent observations on the Galápagos. Grant Terrell, a young ornithologist onboard, remarked that Darwin “seemed to have an intuition for looking at birds of islands, which act as laboratories for natural selection.” There’s a lot of endemism on islands, Terrell added, though unfortunately such birds are vulnerable to extinction due to their isolation.

Darwin himself was in a foul mood on the Falklands, calling the place “miserable,” and the landscape “having an air of extreme desolation.” However, he cheered up when he cracked some “primitive looking rocks” and found fossils. Indeed, Darwin’s Devonian fossils lined up with fauna from South Africa, providing a vital geological link, and the naturalist’s observations of geological formations helped prove the emerging theory of Gondwanaland, a supercontinent which broke up during the Jurassic between 160 and 125 million years ago. When he was not taking in plants and ferns, Darwin made astute observations regarding penguins, steamer ducks and “mischievous” striated caracaras. Darwin also observed a curious creature called the warrah, which he described as a cross between a fox and a wolf. “They will be as extinct as the dodo within years,” he remarked, an ominous prediction which unfortunately came to pass when farmers hunted the creature to extinction by 1876.

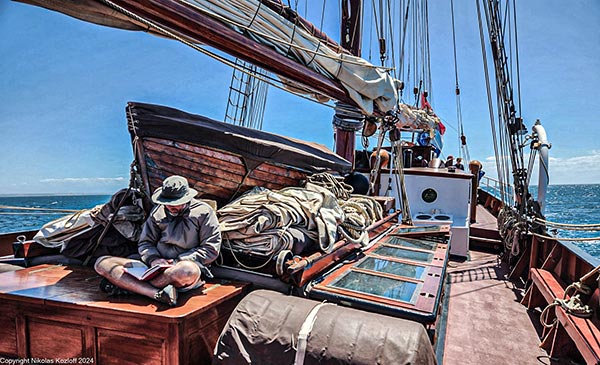

Sailing in the south Atlantic, I began to appreciate Darwin’s physical travails, including sea-sickness. Though the crew provided me with motion sickness pills, I spent the first few days retching. Confined to my cabin, there was little to do but lie in bed, which in turn contributed to back pain. With the ship heeling from side to side, I gripped the wall while showering to avoid cracking my head. Gradually, I managed to adjust to the rocking by gazing at the horizon on deck, which centered my body. My appetite returned, but during meals, the cutlery came flying off the table and skidded behind a piano in the dining room. Passengers were expected to perform on-deck watches lasting between four and six hours. Even in summer, the chill was still all consuming. Unfamiliar with nautical terms such as halyard, jib, and boom, I could scarcely coil rope. During one harrowing early morning watch, I pulled ropes with all my might as sails flapped in the wind. Slipping, I felt like I was getting in the way of the crew.

In addition to physical challenges, I also felt at sea socially. I hadn’t been outside my home base of New York since before the pandemic, and gauging group dynamics can be a challenge for me, even under the best of circumstances. Many of the cameramen and passengers knew each other from previous legs of the expedition, thus accentuating my outsider status. The fact that I received a diagnosis of sorts as being on the autism spectrum probably did not help matters, since focusing on my special interests is much easier than navigating novel social situations. More broadly, “neurodiversity” and its role in steering human evolution no less is absorbing to me personally, and I have given considerable thought to the issue. In this sense, perhaps I share something with Darwin: though it’s difficult to psychologically assess historical figures, some believe the naturalist had Asperger’s, since he avoided human interaction, wrote notes as opposed to dealing with people in person, and was compulsive and ritualistic. On the other hand, perhaps Asperger’s helped Darwin develop his ideas, since it allowed the scientist to hyperfocus while encouraging intellectual independence.

Feeling like a fish out of water on deck, I caught up with first mate Jenny Wagner below, who explained she was a great admirer of Beagle captain Robert FitzRoy. Given the high stakes of climate change, was our ship adhering to sustainable standards? Though the Oosterschelde is a sailing vessel, the ship also relies on a diesel-powered engine at times. On the other hand, the ship had recently installed a new battery system, which cut down on generator hours and this in turn conserved fuel. Jan-Willem Bos, the ship’s captain, said he had not experienced difficulties on the high seas specifically tied to climate change, though sometimes he was taken aback by intense or oddly timed storms. Pondering such questions, I wondered what we would encounter once we hit land. Indeed, climate change is a concern in the Falklands, where drying landscape, cracked peat, erosion and empty ponds have become evident.

Before disembarking on stark and sparsely populated Weddell Island, located in the southwest of the Falklands archipelago, we washed our shoes in disinfectant to prevent the spread of bird flu. News reports suggest protocols are well-needed: almost 96 percent of Patagonia elephant seal pups living at breeding sites in Argentina where bird flu was detected recently died and spread of bird flu is exacerbated by disruptions in bird migration and climate change. Avian flu has also broken out in the Falklands, and albatross remain under threat from the disease. That’s hardly a welcome development for albatross, which are already pursuing “divorce” due to climate change. Normally quite monogamous, breeding pairs are now struggling with fertility in years when the sea is unusually warm and hence “resource-poor.” Indeed, it’s unclear whether the Falklands will continue to be a seabird breeding “hot spot,” since warming seas can impact birds’ food supply.

Home to gentoo and Magellanic penguins, Weddell features plains, rocky hills, and remote coves. Livestock introduction has led to vegetation changes and erosion, but Weddell has turned towards sustainable farming and seeks to manage native tussac grasses which birds rely on for nesting. On the pier, I met local resident Stephen Clifton, who remarked that it has become windier and “there doesn’t seem to be any real seasons anymore.” Meanwhile, dry spells have impacted sheep farming and led to reductions in stock.

Nearby Saunders Island is recognized as an “important plant area,” and home to albatross as well as four species of penguins. On the first day of our visit, I was disoriented by the weather since I found myself sun-burnt, yet chilled at the same time. With hail raining into my eyes, we made our way onshore in a dinghy in what felt like D-day. Unsure if I would fall, I clawed my way up a sandy cliff face while straining to catch my breath. Returning to the island the following day, our ride was smoother in the dinghy, yet looking down, I noticed that somehow, I had cut my finger in the boat. With no trace of people during our strenuous hike, it was surreal to come across a small settlement. Emerging from a shed, I met David Pole-Evans, owner of the island. “You need to survive on your own out here,” he remarked, gazing at the bandage on my hand. “I’m an electrician, plumber and sheep farmer.”

“Over my sixty-five years,” he went on, “I’ve observed climate change affecting Saunders a lot. Summers have been much dryer. It’s gotten so dry that we’ve had to cut down on livestock because there’s not enough water or grass. Meanwhile, though they don’t classify it as hurricanes, we’re getting winds of more than ninety knots.” He added, “it is getting harder for albatross to build nests because it’s much dryer in September, when birds arrive back, than it used to be.” What about kelp farming, I asked — could this be a sustainable alternative for the islands? Kelp forests provide many benefits to both nature and people, and form the basis of ecosystems. What is more, recent findings suggest kelp can assist in carbon removal and therefore act as veritable “carbon sinks.” Perhaps, Pole-Evans remarked, though “no one’s doing anything about it.” Additional resources should be deployed for tussac restoration, meanwhile, which would halt erosion.

On the other hand, during our next stop on Carcass Island, I spotted a substantial amount of tussac on the coastline. The island is an important bird area and hosts the endemic Cobb’s wren as well as songbirds such as the tussac bird. Striding into the front yard of a local lodge, I spotted one of Darwin’s “mischievous” striated caracaras. Local resident Derek Goodwin, who was leasing the lodge, drove me and some passengers to an elephant seal colony, where the animals nestled in tussac. Echoing what I’d heard earlier, he remarked, “the ground is noticeably drier, and most places are complaining of water shortages.”

Exhausted by interminable shifts and unfamiliar onboard challenges, I was relieved to make landfall in Port Stanley. Darwin’s legacy looms large here, from the word Beagle etched into the side of a hill to a distillery offering gin mixed with “Darwin’s botanicals,” to FitzRoy Road East. At the Historic Dockyard Museum, I took in exhibits dealing with Darwin and the warrah. Peeking into a tourist shop, I purchased a jar of diddle-dee berry jam, apparently one of the few products native to the Falklands. We then jumped in a sturdy jeep with Linda Buckland, a local guide, and made our way through barren landscape. “The biggest stone run in the Falklands is called Princes Street,” she explained, “because when Darwin saw the formation, it reminded him of cobble streets in Edinburgh.”

As we visited graves of the fallen from the 1982 Falklands War, I ran into difficulty with the weather, which fluctuated between balmy and sheets of rain. With no restaurants, I had to make do with sugary snack bars purchased from a convenience store. Driving past a meager lake, Buckland explained wind had dried up the landscape. Back in Stanley, our party headed to a local restaurant. Our food was slow in coming, and in the meantime, I gulped a local beer on my empty stomach. Suddenly, the room started heaving as if I was back on the boat. Feeling dizzy and faint, I blacked out for a few moments. One of the passengers from the Oosterschelde, a survival guide, grew concerned I’d had a seizure and insisted I pay a visit to the emergency room.

At the hospital, attendants prodded me to draw blood and placed me on an IV. As per my onboard experience, the multi-national character of hospital staff was diverse, ranging from a kindly Irish doctor to Aussie and Zimbabwean nurses. After finding I had merely fainted due to dehydration, the staff released me. Perhaps my body had given out after being exposed to strange weather and weeks at sea? Leaving the hospital, I reflected on the irony of becoming dehydrated surrounded by such balmy weather. Shuttled back to my motel in an ambulance, I recounted my experiences to the driver, who hailed from the island of St. Helena. Feeling weak, I took in Stanley over the next few days, an odd English outpost in the south Atlantic. Walking outside town, I was blown off the road by strong winds and got caught in a hailstorm.

As I strode along a pier frequented by sea lions and hordes of disembarking tourists, I came across a native plant garden belonging to local environmental group Falklands Conservation. Esther Bertram, CEO of the outfit, remarked the islands already exhibit an extreme environment, and currently “we’re at the stage where we just need any native habitat to grow.” Winds are strong, she added, and with increased storms those winds are set to increase, thus drying out the climate. When I asked if she was concerned about the plight of specific types of vegetation, she answered, “all of it.” Falklands ecology has shifted massively since Darwin’s day, with only a tiny fraction of tussac habitat remaining. Unfortunately, however, replanting tussac was a massive logistical challenge. Die off of local vegetation, meanwhile, was a particular concern for the Cobb’s wren, which thrives in dense tussac habitats. And what about cultivating diddle-dee berry as a sustainable resource? “No, we have a problem with die-off. We don’t really know what’s causing the issue.”

How do all these immediate environmental concerns stack up to longer evolutionary change? For context, I caught up with Emma Brook, a geologist and college manager at Falklands College. “I think Darwin was confused,” she remarked, “because his fossils were old, but he couldn’t say how old.” As it turns out, geology on the Falklands is remarkably ancient, with some rocks dating back a billion years. Now, however, the islands must adapt to a much speedier timeframe since glacial melt could result in open sea overwhelming Stanley harbor. West Falklands, meanwhile, could be flooded and split into two separate islands.

Faced with these odds, Brook suggested we may have to start thinking creatively to confront complex global challenges. Darwin, she remarked, was on the autism spectrum since he was reclusive and “found it a little bit difficult to get on with people.” On the other hand, “sometimes people with autism have that ability to really focus and think for long periods of time about certain issues. I would say that anybody who is neurodiverse has something to offer science, because these folk look at the world in a different way.” In a sense, human evolution requires neurodiversity: while some individuals excel at repetitive tasks, “just as important are those who are extroverted, who pull people forward. You need both for society to work.”

Leave a comment