Ukraine: Reflections on Secessionist War, Gender Equality, Rightwing Battalions and Kyiv’s “G.I. Jane”

Could Ukraine’s secessionist war actually encourage more gender equality? Following my first trip to Kyiv almost three years ago, I would have been skeptical of such views. During interviews, political activists on Ukraine’s independent left circuit expressed dismay over sexism during the Maidan revolution which toppled the unpopular, pro-Kremlin government of Viktor Yanukovych. During the revolt, some estimate that almost half the protesters on Maidan square were women, yet according to observers some men discriminated against their female activist counterparts.

Natalia Neshevets, a young activist, told me that men would frequently exhibit sexist attitudes, for example by ordering women to clean up or assume a subordinate role. It was also frustrating, Neshevets says, to observe how men tended to dominate political discussion. The activist added that the war with Russian-backed separatists, which erupted shortly after the Maidan revolution, had diverted vital attention from women’s rights and “of course the media exacerbates the problem by talking about the war all the time while all other problems are minimized. In this manner, feminist issues become invisible.”

Last year, feminists, leftists, anarchists and representatives from human rights and LGBT groups staged a demonstration in Kyiv to protest violence against women. For organizers, taking action has assumed greater importance within the new wartime context. Indeed, war in the east has reportedly exacerbated gender violence on both sides of the conflict. Acts of violence take multiple forms and have been known to occur at checkpoints, in illegal sites of imprisonment (also known as “cellars”), and within families of ex-soldiers. Prior to the demonstration, rightist groups threatened to upstage the event and during the protest, violence erupted when masked assailants tried to throw bright green disinfectant on participants. The suspects were later taken into police custody and identified as members of far right group Revansch or “Revenge.”

Women and War

Despite such reports, Kyiv’s ongoing conflict with Russian-backed rebels in the country’s east has in many ways upended traditional notions of gender relations. As the war has dragged on, women have played an important role both on and off the battlefield. That, at least, is the impression I got after my second trip to Ukraine late last year. Yavtokia Popovich, a doctor who signed up as a volunteer medic on the front lines, told me “There are many women on the battlefield now serving as doctors as well as soldiers. Everyone respects them on the front line.”

In a certain sense, Popovich’s statements aren’t so surprising: there’s a long tradition of Ukrainian women serving in combat, including for example the Soviet Red Army. Nevertheless, for much of the separatist war, which first erupted in the spring of 2014, Kyiv prohibited women from fighting on the front lines. To be sure, 17,000 women still served the military effort, though “officially” they only occupied supporting roles working as medics, cooks, accountants, engineers and administrators. Last year, however, the government changed the rules and women, who account for twenty five percent of the armed forces or 250,000 individuals, were allowed to serve as military vehicle commanders, machine gunners, mortar commanders, scouts and snipers.

Today, women soldiers serve alongside their male counterparts while exposing themselves to the same level of mortal risk. Speaking with Popovich, the medic tells me that for her, joining the war effort was a personal matter since both her sons-in-law had deployed to the front lines and she observed that military personnel were not being adequately cared for. During her stint as medic attending to the wounded, Popovich has dealt with all kinds of injuries ranging from shrapnel to bullet wounds and the like. When asked her about her worst experiences on the battlefield, Popovich responds “almost every day I get into a dangerous situation.”

Paradox? Women and Right Wing Battalions

Popovich and medical personnel have certainly displayed great courage and even heroism in attending to the wounded, though officially they are linked to the Ukrainian military. Other women, however, have gone outside normal channels in an effort to see action on the battlefield. In the initial stages of the war, before the government had provided “official” combat status for women, many served “under the radar.” In reality, this meant linking up with so-called “volunteer battalions,” some of which were nothing more than improvised nationalist- paramilitary outfits.

Last year, Newsweek profiled one such fighter, Lera Burlakova, who first traveled to Ukraine’s Donbass region as a journalist. After a week spent covering the war in the town of Pisky, Berlakova signed up with Praviy Sektor or Right Sektor, one of the most notoriously far right volunteer groups. The outfit has denounced the LGBT community and even clashed with Ukrainian law enforcement. A far cry from other, more apolitical civilian volunteers, Right Sektor has even adopted symbols from the Ukrainian nationalist opposition during World War II, factions of which allied to Nazi Germany at one point.

There is a certain tradition of Ukrainian women linking up with such nationalist forces. Indeed, though women fought in the Soviet Red Army during World War II, they also served in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army or U.P.A., an anti-Soviet force which at times allied with the Nazis and committed atrocities against the Jews and other ethnic minorities (later, the U.P.A. turned against Germany). To this day, right wing forces such as the Svoboda political party idolize the U.P.A. and brandish the group’s nationalist flag.

From Volunteer Battalions to “Official” Army Status

To be sure, Right Sektor was only one of more than forty volunteer battalions fighting in the east, and few of the others espoused such extreme views. Nevertheless, American photojournalist Sarah Blesener, who embedded with Right Sektor, observed that Burlakova was hardly alone and “The first thing I noticed was how many girls and young women were there.” The case of Burlakova raises the question of whether fighting for a group espousing objectionable views can actually advance the cause of women’s rights.

Speaking with Newsweek, Burlakova defended her decision, remarking that she did not support rightwing ideas but on the other hand Right Sektor allowed her to fight. In the course of her reporting, Blesener noted that Right Sektor members displayed swastika tattoos. “It is shocking,” she said, “that a unit can at the same time embody virtues that I respect—such as allowing women to fight on the front line of combat—yet, on the other hand, be known for nationalistic rhetoric, Russophobia and hate speech.”

Women have also enlisted in another volunteer battalion called Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists or O.U.N., which takes its name from a partisan outfit dating back to before World War II. While the O.U.N. fought the Soviets and strived for an independent Ukraine, many leaders were influenced and trained by Nazi Germany. Indeed, the O.U.N. could be characterized as a far right terrorist group which hoped to consolidate an ethnically homogenous Ukraine and a totalitarian, one party state. Like the U.P.A., the O.U.N. engaged in atrocities against Jews and others during the war, for example in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv.

Are female conscripts advancing the cause of women’s rights by signing up as conscripts within such questionable units? It seems rather doubtful, though to be sure women reportedly demonstrate a remarkable willingness to confront prejudice and discrimination from their male counterparts within volunteer battalions. To top it off, once volunteer battalions were disbanded two years ago, women ran into problems getting properly recognized by the official armed forces. Matters were brought to a head in July, 2015 when Right Sektor staged an armed standoff with Ukrainian police officers. Alarmed that rightists had become too unruly, President Petro Poroshenko ordered militias to stand down and join the official armed forces.

At that point, many Right Sektor troops enlisted in the army, though women were barred from following suit. Women such as Burlakova, who had previously been affiliated with militias, managed to get around that rule by registering as medics while continuing to fight as de facto ordinary soldiers. As a result, however, there is no official documentation of women soldiers seeing combat during this time, which in practical terms means they were excluded from pay and benefits. It wasn’t until June, 2016 that the government finally opted to define women’s status more clearly and the latter were officially allowed to fight.

Questionable Aidar Battalion

Perhaps, if Nadia Savchenko runs for president, the questionable record of volunteer battalions will be subject to more public scrutiny. Savchenko, a celebrated woman fighter pilot who was captured by the Russians and then released in a prisoner exchange, has been touted as a possible presidential contender though her links with rightist Aidar Battalion may raise eyebrows. One of the most notorious and visible units fighting in eastern Ukraine, Aidar has been criticized for violating human rights of civilians and enemy combatants within the conflict zone.

Amnesty International has documented Aidar’s record which includes abductions, unlawful detention, robbery, extortion and possible executions. Going further, Amnesty remarks “Some of the abuses committed by members of the Aidar battalion amount to war crimes, for which both the perpetrators and, possibly, the commanders would bear responsibility under national and international law.” In one case, Aidar battalion members dressed in camouflage abducted four miners from a small town, but not before breaking the jaw of one of their victims. Aidar battalion placed tape over prisoners’ eyes and the men were taken to an unknown location. Detainees were reportedly beaten unless they agreed to sing the Ukrainian national anthem.

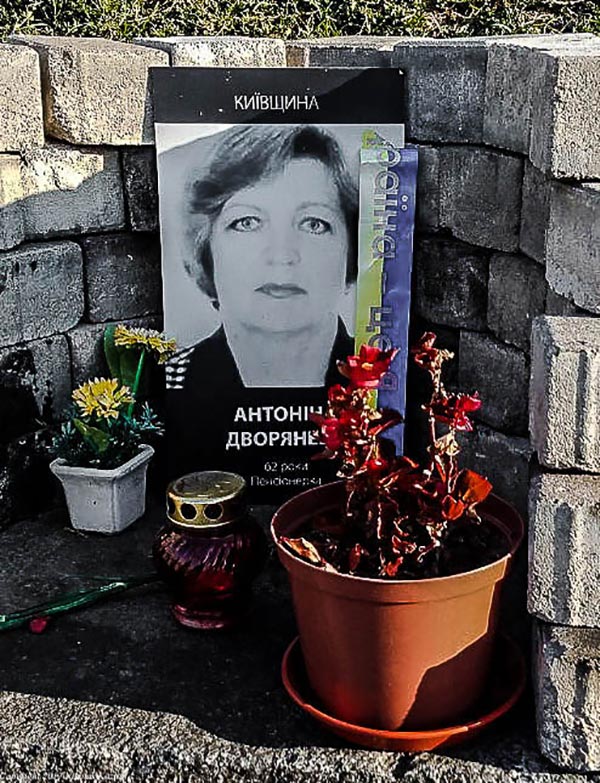

Serhiy Melnychuk, an MP and founder of Aidar Battalion, is a questionable character. Reportedly, he recruited completely inexperienced people for his unit, including homeless and pensioners. Nevertheless, the new conscripts acquired weapons from the Defense Ministry, as well as backing from wealthy oligarch Igor Kolimoysky. Melnychuk has said that his volunteers had all fought on Maidan square and therefore “didn’t need military training.” The MP now faces charges from his time in the east, including robbery and forming an illegal group. When the government ordered Aidar to disband and merge with the army, Melnychuk described the order as “criminal.” Reacting to the authorities’ crackdown, Aidar Battalion picketed the Ministry of Defense and set fire to tires. In response to the event, Melnychuk was expelled from his coalition party. Reportedly, most Aidar combatants have now demobilized or come under official state control.

Curious Case of Nadia Savchenko

Is Nadia Savchenko, who served in Aidar Battalion, a model for women? The former pilot is hailed as a modern “Joan of Arc” and has become a kind of “G.I. Jane” to many Ukrainians. Savchenko’s bio reads like something out of a Hollywood script: defying the odds of her male-dominated culture, she became Ukraine’s first female pilot, graduating from the prestigious Air Force University in 2009. A veteran of Ukraine’s mission to Iraq, Savchenko learned how to fly Mi-24 attack helicopters.

Later, she participated in demonstrations on Maidan square and when unrest erupted in the east, Savchenko decided to volunteer with Aidar Battalion. While serving with the unit, Savchenko was captured by Russian separatists. Charged for alleged complicity in the deaths of two Russian journalists who had been killed in a guided mortar strike, she was hauled off to Moscow. According to Western officials and human rights groups, the charges against Savchenko had been fabricated, and Russia subjected the Ukrainian to a show trial. In the course of the trial, however, Savchenko became a national hero back home for her political defiance. Literally addressing the court from a cage, she refused to ask for clemency and gave the judge the finger. With her close-cropped hair, Savchenko sang the Ukrainian national anthem while belting out an anti-Putin speech.

Hardly amused by such antics, Russian authorities sentenced Savchenko to twenty two years in prison, while tabloids called her “Satan’s daughter,” and a “killing machine in a skirt.” In late 2014, she began a hunger strike and refused to eat even after guards fried potatoes and onions under her nose. Savchenko’s case attracted international attention and back at home President Poroshenko himself awarded the veteran the Hero of Ukraine medal. In addition, during her stay in prison, much of it spent in solitary confinement, Savchenko was elected to parliament in absentia on the ticket of former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna Party.

Problematic Politics

Under a prisoner exchange arrangement, Savchenko was released and given a hero’s welcome back in Kyiv. Rather audaciously, the veteran remarked that if the Ukrainian people wanted her to run for president she would do so. “It’s an honor to be compared with Joan of Arc,” she declared. Politico reports that “our Nadia,” as she is known, is regarded as less of a politician and more a symbol of Ukrainian defiance. Reportedly, some rural Savchenko supporters literally wear icons of their hero around their necks.

Perhaps, Savchenko may find a receptive audience in post-Maidan Ukraine, now disillusioned with corruption and the slow pace of reform, not to mention a president whose offshore shell companies have been exposed through the Panama Papers. In time, Savchenko may wind up campaigning against Poroshenko himself, who helped to secure her release in the first place. It’s unclear, however, what Savchenko really stands for politically as her core beliefs are unknown. For the moment, she seems to be following in the footsteps of Ukrainian populists by railing against corrupt parliamentarians and even criticizing the top brass as incompetent. Would a Savchenko presidential bid tilt to the right, like other populists such as Oleh Lyashko of the Radical Party? Savchenko’s earlier ties to Aidar Battalion and her defense of the unit seem to hint at the possibility. “You sit on the couch and ask us how we fought. We fought the way we had to. Or you think that saints are fighting there?” she has said.

Ironies of Ukrainian Feminism

In the midst of deadly war, Savchenko has become one of the most visible female icons in Ukraine, though this has obscured the country’s longer historic tradition of feminist politics which has proceeded along somewhat different lines. Perhaps, Savchenko’s newfound fame isn’t so surprising given that the secessionist conflict seems to have attracted women of certain political and nationalistic stripes rather than others. A century ago, however, women served as reconnaissance scouts in the anarchist and peasant rebel army of Nestor Makhno. Indeed, during the Ukrainian Civil War of 1917-1921 women joined Makhno’s caravan since anarchists respected women more than the Bolshevik Reds or Whites, whose troops displayed an appalling record of rape.

In addition to this military record, women may boast a long and illustrious feminist tradition in Ukraine which arguably rivals that of western-style feminism, and in this sense it is somewhat ironic that Savchenko of all people has become something of a poster child for women’s struggle. Take, for example, Lesya Ukrainka (1871-1913), a noted Ukrainian feminist essayist, poet, critic and dramatist, not to mention a pioneer who turned people’s attention to women’s rights and voting suffrage. On Maidan square protesters erected a portrait of Ukrainka, though perhaps she deserves more visibility. A Marxist, Ukrainka opposed the Czarist regime and translated the Communist Manifesto into Ukrainian.

Hollow Soviet Feminism

Later, Soviet women arguably attained more political and social equality than their western counterparts. In 1917, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic introduced female suffrage. Three years later, the entire Soviet Union legalized abortion. Furthermore, women developed their own, mass-based organizations such as the Ukrainian Women’s Union. Established in 1934, the peasant-based organization recruited almost 100,000 members while setting up child care centers and cooperatives for women’s crafts. Yet underneath these advancements, Soviet society proved to be backward, patriarchal and resistant to change.

Indeed, writes Foreign Policy magazine, the Soviets heralded women “as equal to men in the workplace, but still expected flawless performance of housewifely and motherly duties. Maybe that’s why the trappings of Western feminism — which many Ukrainian women see as dismissive of femininity — hold little appeal.” Dafna Rachok, a gender studies expert at the Central European University, adds “Though it is sometimes stated that the U.S.S.R. emancipated Ukrainian women and that the post-socialist regime pushed them back into the kitchen, there’s very little evidence to support this claim. In any case, these changes didn’t really free women from the double burden of having to take on work and domestic chores.”

Where is Nadia’s Counterpoint?

While Soviet bureaucrats may have reasoned that society as a whole would rush to embrace feminist-style change, it’s unclear whether top-down decisions were ever fully understood or embraced by the public. Yet Ukraine is also something of a paradox, since the country has spurred the growth of well-known groups such as FEMEN in more recent times. Established in 2008, FEMEN has been a vocal opponent of far-right politics throughout Europe and has achieved notoriety for its topless protests. The group began as a decidedly modest affair with the emergence of a Ukrainian feminist club focusing on opposition to patriarchal traditions within society.

Original founders of the group were concerned about abusive fathers or boyfriends, mothers who supported families in the midst of men turning to alcohol, not to mention prostitution and sex-trafficking which has ravaged post-Communist Ukraine. Activists dressed in pink and held marches, yet they were ignored. Changing tactics, they decided to take their clothes off to garner more attention. Speaking to the New York Times, one member remarked “We were trying to say the truth. But no one was interested in it, and we understood that this society, this country, is not ready to listen to women. But everyone wants to look at them, especially if they are naked. We understood O.K., if we are not able to talk, we will show.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the new strategy took off and FEMEN quickly developed into an organization with international reach, spurring chapters in a whopping nine countries spanning four continents. Volunteer women “shock troops” quickly perfected the art of so-called “sextremism” in the war against patriarchy, organized religion, sexual exploitation and dictatorship. The protests caught male law enforcement off guard, which was forced to awkwardly conceal partially dressed women who would wiggle away. Other women protesters, who tend to be on the young side, were beaten, jailed or threatened with death. Needless to say, it wasn’t long before FEMEN left Ukraine altogether after police claimed to have discovered weapons in the group’s offices. FEMEN said the weapons had been planted, and founders left Ukraine out of fear for their lives. Currently, the organization’s headquarters is located in Paris.

Mixed Post-Maidan Milieu

Swaying Ukrainian women to their cause, not to mention wider society at large, was never going to be easy for FEMEN. Yet the group hasn’t been immune from its own internal problems, with some members opposing FEMEN’s international expansion and seeking to retain the outfit’s “old way” of operating under original Ukrainian leadership. Underlying factionalism raises the question of who speaks for FEMEN or international feminism for that matter. Though FEMEN aims to publish a book which will elucidate the group’s overriding vision of modern feminism, others disagree with the group’s political tactics and specifically attention-grabbing nudity.

During my recent trip to Kyiv, I got back in touch with Nataliya Neshevets, the Maidan political activist who I had interviewed two years earlier. FEMEN did not have a visible presence on the Maidan, she says, and, if anything, some in the crowd proved hostile to a feminist message. On the square, she says, feminists were physically attacked “not so much by far right groups but by older people who were simply passing by, say men and women over the age of fifty.” Needless to say, Ukraine’s post-Maidan politics hasn’t assumed a particularly feminist bent, either, and the government has failed to provide funding toward women’s issues.

On the other hand, Neshevets adds, “Feminism is growing and maybe there’s more awareness about these issues now. The media is raising the issue of women. Four or five years ago feminism was stigmatized more but today public figures and writers are broaching the issue.” The activist declares, “I’m not sure if this was a result of Maidan, but maybe things started to snowball as a result of rebellion.” Meanwhile, the public has elected young women to parliament who are playing an important role in pushing political reform, and needless to say women are more visible now in civil society, journalism and the military of course. Other, more radical voices however remain unconvinced. One of the co-founders of FEMEN told the New York Times that it may ultimately take a true revolution to improve women’s lives.

Leave a comment