Ukraine: Developing an Authentic “Counter-Culture” Will Be Difficult

As an idealist, I always like to assume that radical revolutions will inevitably cultivate a kind of “counter-culture” in opposition to the establishment and prevailing norms. Take, for example, the Mexican Revolution with its mural art, or even the Russian Revolution which in its initial phase at least spurred great innovations in film. In more recent times, the ’60s generation developed its own radical counter-culture based around music. To what extent have other rebellions developed their own distinctive cultural voice? For answers, I traveled late last year to Ukraine where I spoke with local experts.

Just over a year ago, demonstrators associated with the so-called EuroMaidan movement overthrew the unpopular government of Viktor Yanukovych. To be sure, the revolt displayed radical traits or characteristics during its latter phases, though it would be difficult to claim that revolt in Kiev amounted to a genuine revolution which fundamentally altered the political, let alone social or cultural structures of society. That, at least, is the impression I get from speaking with observers who feel disheartened by Maidan, a movement which in their view failed to promote truly ground-breaking change in the local arts scene. Indeed, even though Maidan provided a brief but welcome breath of fresh air, artistic self-expression has confronted many barriers from religious conservatism to institutional self-censorship to right-wing nationalism.

Eyewitness to Local Arts Scene

Larissa Babij, an arts curator living in Kiev, is a veteran of such cultural battles. An American of Ukrainian descent, Babij moved to Kiev in 2005. She never really saw herself as a political activist, but when the curator observed that Ukrainians had little sway over their own cultural institutions she helped to found a group called Art Workers’ Self Defense Initiative. The original group was comprised of between ten and twenty people, many of whom knew each other personally and had collaborated over the years. The tight-knit nature of the group allowed the outfit to act nimbly and effectively, though some charged the organization became “cultish” after a certain point. Eventually, Babij tells me, organizers decided to open the group up to other participants.

In a sense, it’s hardly surprising the Ukrainian public would seek to play a greater role in museum affairs. Writing in the Brooklyn Rail, arts curator Olga Kopenkina notes that the local arts scene has generally “oscillated between Ukrainian oligarchic capital and big state-supported museums and institutions.” Kopenkina adds that “state museums and institutions exercise a heavy-handed control over cultural production and display,” and the contemporary art world “seems to gravitate toward a few established art centers that are financed and empowered by industrial tycoons and the wives of dodgy politicians.” Meanwhile, there is a real lack of small, artist-run spaces and many museums suffer from neglect with some simply unable to pay their electricity bills, thus obliging visitors to view displays in complete darkness.

Museum Controversy

Given this bleak milieu, public pushback was probably inevitable. Take, for example, a 2012 controversy which erupted at the state-funded National Art Museum of Ukraine (or NAMU). According to Babij, NAMU has “always been a relatively conservative museum.” On the museum’s first floor, she adds, NAMU’s permanent collection featured cautious exhibits dealing with Ukrainian icons such as literary legend Taras Shevchenko. On the second floor, however, NAMU showcased rotating exhibits, and in 2009 the museum started to promote some “weird and quirky projects.” Babij herself organized some performance art at NAMU during this period, which was the first time such presentations had been allowed.

NAMU’s brief foray into free artistic experimentation threatened to be upended, however, when the museum’s director was abruptly replaced. The cultural community as well as local museum professionals suddenly became worried that NAMU’s new director would set a different course for the institution. What is more, protesters charged the administrator was incompetent. A small number of people decided to act by staging a series of protests and writing letters and petitions to the Minister of Culture.

In an effort to safeguard NAMU from petty private business interests as well as government interference, activists also called for greater transparency in the selection of a new director. Protesters were joined by museum staff, which suffered from low pay and poor morale. Together, they held meetings on the premises of the museum, and eventually demonstrators managed to pressure the Minister of Culture into appointing a new director who was regarded as more qualified to oversee NAMU’s work.

Religious Tensions

As if such institutional pressures were not enough, activists have also been pitted against innate religious conservatism. Such tensions were placed on vivid display during yet another controversy, this time involving Kiev’s Mystetskyi Arsenal art museum. In July, 2013 the institution put on a show titled “The Great and the Grand.” The exhibit was designed to celebrate the 1025th anniversary of the baptism of Kievan Rus, which is the original medieval state considered to be the Orthodox foundation of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. In a very symbolic sense, then, the show was designed to foster closer cultural ties between Ukraine and Russia, and indeed Putin himself was invited to the show. Furthermore, President Viktor Yanukovych exercised great influence over Arsenal, a museum which lacked its own political autonomy, even though the institution is state-funded and receives taxpayer money.

As if the political dimensions weren’t questionable enough, further questions soon arose about the relationship between church and state. When it became clear the show was to be partially funded by top-ranking clergy linked to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Babij grew concerned. Could the president be seeking to perpetuate his own state ideology favoring closer ties to the Church? As suspicions grew, a controversy erupted at the museum which eroded Arsenal’s already fast deteriorating reputation. On the night prior to Yanukovych’s personal visit to the museum, Arsenal’s director Natalia Zabolotna literally took a can of black paint and doused one of the exhibit’s artworks which she deemed immoral.

Politics of Fear in Arts Community

The work in question, a mural depicting a flaming nuclear reactor with priests and judges partially immersed in a vat of red liquid, soon became a cause célèbre as Kiev’s arts community rushed to the defense of creative self-expression. Prior to the opening, eight activists were arrested outside the museum protesting the creeping consolidation of church and state. In defending her controversial decision, Arsenal’s director claimed that the exhibit “should inspire pride in the state.” She added, “if you participate in [an] exhibition dedicated to the 1025th anniversary of the baptism of Kievan Rus, you don’t have to do your best to offend the faithful, to lower the reputation of all clergy.” In the wake of the controversy, Arsenal’s deputy director resigned in protest, while some suggested the director had come under pressure to eliminate controversial work in advance of Yanukovych’s visit.

As the controversy grew more heated, Babij’s Art Workers’ Self-Defense Initiative called for an outright boycott of Arsenal until the museum agreed to safeguard creative self-expression. Curiously, however, the fearful and guarded local arts community failed to rally behind such calls, and even backed Arsenal. In Guernica magazine, Babij notes that boycotters were criticized “for being unconstructive, ineffective, and focusing on their international image at the expense of loyalty to local institutions.”

Nikita Kadan, a local artist, says the entire situation “was awfully similar to Soviet-era public, collective-shaming tactics, through which cultural actors were compelled to participate and atone for their transgressions.” When asked why she thought the boycott didn’t receive more grassroots support, Babij remarks “fear is such a driving force here in Ukraine. If I say something against this institution, there’s a fear of losing a possible opportunity. If I offend someone, I won’t be able to show my work at the Arsenal. And if I never show at the Arsenal, then how will I advance my career? It’s better to cooperate and be nice than lose an opportunity.”

A New Street Aesthetic

Shortly after the Arsenal controversy, however, crowds took to the streets demanding president Yanukovych’s ouster. To what extent can the EuroMaidan movement be seen as a reaction against the stultifying cultural milieu within Ukraine? “I definitely would not call Euromaidan a counter-cultural movement,” Babij notes emphatically while letting out a chuckle. On the other hand, she notes, EuroMaidan “held the potential for a future counter-culture. The way Maidan evolved and the spontaneous way in which people came together and collaborated was really something new.”

According to an article in Wilson Quarterly, “the Maidan itself turned into something of a canvas.” The main centerpiece at Maidan was a large, metal New Year’s tree. However, there were many other localized installations including wooden barricades bearing the names of different cities or districts located throughout Ukraine. Babij adds that street theater and props were also quite prevalent on the Maidan. Indeed, one art collective called Mistetska Sotnya performed a variety of different shows in the streets which featured musicians, circus acrobats and ballerinas. Somewhat audaciously, performers carried out their shows while standing right at the barricades. Meanwhile, artists decorated shields and helmets belonging to anti-Yanukovych fighters.

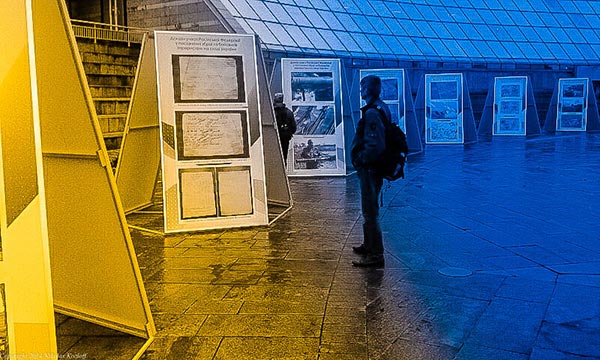

Maidan’s creative output wasn’t merely limited to street theater, however. Take, for example, poster art which dealt with major happenings on the square. Photographers meanwhile distributed images on the internet and held impromptu exhibitions at the barricades. Ornamental painting and portraits were also visible within the vicinity. In addition, Maidan spurred the growth of documentary film. Meanwhile, a number of noted musicians played a piano which had been painted in the Ukrainian national colors of blue and yellow. The piano quickly became a symbol of revolution.

A Different Cultural Take on Maidan

Though certainly prodigious and impressive, Maidan’s creative outpouring was not always associated with moves toward a “counter-culture.” Indeed, art even took on an outright nationalist or rightist complexion in many cases. Take, for example, the emergence of so-called “zhlob” artists allied to the far right. According to Babij, zhlob artists are “very aggressive” and populist. Such tactics have increased the group’s visibility and popularity. For some time, the zhlob movement has displayed its work at a local gallery in Kiev.

In the words of Babij, zhlob art is “intentionally low-brow.” In one recent gallery exhibit, zhlob artists literally placed a couple of Russians inside a cage. Later, on the Maidan, zhlob artists had their own tent which acted as a makeshift gallery. During anti-Yanukovych protests, rightist artists sought to demonstrate their patriotism by accusing other artists, particularly left artists, of not being sufficiently politically active.

Perhaps, the zhlob movement underscores a disturbing move to the right in Ukraine’s cultural milieu. According to artist Nikita Kadan, the same people who supported Arsenal’s director Zabolotna and ostracized boycotters later adorned themselves with ribbons and EU symbols while coming out in favor of the EuroMaidan revolution. “How do they reconcile participating in the ideological design of Yanukovych’s government by uncritically supporting Mystetskyi Arsenal on the one hand, and protesting against that very same government on the other?” asks Kadan. “Somehow the contradictory nature of doing so escaped them,” the artist adds.

Arts and Culture in the Post-Maidan Milieu

In a local Kiev café, Babij elucidates her own somewhat skeptical perspective on the post-Maidan cultural milieu. In the winter and spring of 2014, she says “something really changed in Ukraine. There was a potential for a revolution. In the end though it turned out to be a circular revolution where you come back to a certain point where you were before.” Rather than Maidan having changed the wider society, “it’s more like Maidan took place and arts institutions are continuing to look and think in the same way that they did before. Within this context, Maidan simply becomes another ‘theme.’ There’s a Maidan museum where they exhibit artifacts. Maidan objects have been ‘fetishized’ and painted helmets are displayed to the public. Unfortunately, however, we’ve already forgotten what Maidan was originally about.”

Meanwhile, a big cloud still hangs over Mystetskyi Arsenal, which recently announced that it would cancel its 2015 Kiev International Biennale. Officially at least, controversial director Zabolotna has claimed that the museum cannot move forward with the exhibit due to armed conflict in the east and uncertain economic conditions within Ukraine. Perhaps, however, the country would have had difficulty guaranteeing the safety of progressive artistic types taking part in the proceedings. Last September, contemporary art curator and left political activist Vasyl Cherepanyn was brutally attacked in broad daylight by right wing thugs. What is more, some within the Ukrainian art community are still indignant over Zabolotna’s previous censorship and several even called for a boycott of the Biennale in any case.

Reflecting on the events of the past year or so, Babij says the entire political cycle has left her feeling “pessimistic and amazed.” Indeed, the curator notes, Ukraine is now awash in nationalism which may hinder the emergence of a more progressive arts scene. “In general,” she says, “the Ukrainian public has a pretty simplistic idea of culture. I don’t think political parties for that matter have any articulated cultural policies and they probably wouldn’t differ from one another too substantially.” Moreover, any effort to promote a kind of “feel good” mood in Ukraine via art seems to miss the point. “I don’t think it’s very realistic,” Babij remarks. “How are we supposed to understand other people, just paint each other blue and yellow?”

Leave a comment