Reflections on a Voyage to Odessa, Isaac Babel, the Holocaust and Anti-Semitism

I have always had a romantic fixation on the Black Sea port of Odessa, home to swashbuckling thieves, miscreants and all manner of shady and colorful characters. In the early twentieth century, iconic native son Isaac Babel memorialized the city’s Jewish ghetto, known as Moldavanka or the “Moldovan girl.” In his story “The Father,” Babel memorably described the so-called “kings of Moldavanka,” Jewish bandits riding atop carriages and frequenting local brothels. Babel himself admired Jewish gangsters, and one of his literary characters, “Lyubka the Cossack,” was an intimidating woman smuggler. Other Babel characters include Benya Krik or “the King,” who shakes down his enemies while displaying utter contempt for the police. Babel was fond of describing Odessa’s local merchants, who routinely unpacked cargo full of cigars, delicate silks, cocaine and tobacco. “Every object had its price,” the scribe wrote, and “they washed down each figure with Bessarabian wine.” In one story, “Odessa,” Babel’s narrator says the city is the most charming settlement within the Russian Empire, which is chalked up to the town’s substantial Jewish population. At one time, a rich cacophonous medley of Ukrainian, Russian and Yiddish could be heard on city streets.

Today, the old Moldavanka has largely disappeared though the city hardly disappoints. Having attended the 75th memorial commemorations of the Babi Yar massacre in Kyiv, which almost dealt a fatal blow to Ukraine’s Jewish population, I decide to take a rickety, Soviet-era plane down to the Black Sea port. While walking around Odessa itself I am struck by the city’s ornate, neo-classical and over the top Moorish Venetian architecture dating back to Czarist times. Having languished since the Belle Epoque, Odessa has a rather decayed air about it. “Odessa of yesteryear,” notes Haaretz, “is one of those cities which has etched itself in collective memory as it was in its prime – like 19th-century Paris, or Berlin in the 1920s or New York in the seventies.” If I were to collect bricks or materials from most any house in Odessa, I wonder, would they simply crumble into dust while lying in my hands? Babel and the old Jewish world which he inhabited seems long gone: indeed, up until recently when the city erected a monument to the writer in a local plaza, literary fans had to content themselves with a modest plaque hanging over the scribe’s former apartment building.

A Visual Tour of Odessa

Having previously spoken with Jewish experts in Kyiv about the thorny problem of anti-Semitism, I’m eager to get a clear sense of the local situation in Odessa. Though the city has long been known for its cosmopolitan and multi-ethnic character, Odessa has also witnessed violent anti-Jewish riots. Indeed, the city experienced no less than five pogroms from 1821-1905. Almost every sector of Odessa society participated in disturbances, from wealthy Russian merchants to nationalist Ukrainian intellectuals. Czarist authorities hardly helped matters and actually favored pogroms which diverted social and political discontent. A pogrom in 1871 proved particularly painful for residents of Moldavanka, with rioters destroying more than two hundred local apartments in the neighborhood. The 1871 incident is seen as a precursor to far more serious pogroms in 1881 and 1905.

To get a clearer sense of how people in newly-independent Ukraine are coming to grips with this history, I speak to Pavel Kozlenko, director of Odessa’s Holocaust Museum. Is it fair, I ask, to blame Ukrainians for anti-Jewish violence during the Czarist period considering that everyone was mixed up in the old empire and Ukraine hadn’t yet become an independent country? “The majority of Ukrainians weren’t responsible for violence,” he says, just “certain individuals who made it worse.” Some Ukrainians, he adds, actually helped Jews. And yet, if local Odessa folk wanted to learn more about, say, Moldavanka, where might they turn? Kozlenko says there hasn’t been much of an official effort to promote Jewish culture, and in the specific case of Moldavanka there wasn’t a lot to restore in the first place since the neighborhood merely consisted of humble one-story houses. Today, most of the Jews have vanished from Moldavanka and all the synagogues have been converted into homes or businesses.

From Brodsky Synagogue to Shalom Aleichem

Similar trends seem to be at work in Odessa as a whole, and it’s sometimes difficult to reconstruct the city’s historic Jewish feel. To be sure, the city sports a Hassidic hair salon and even a new Jewish cultural center which opened to great fanfare in 2009 with the help of wealthy American philanthropists. Moreover, Jews occupy prominent positions within local business and political life. Walking near downtown, I spot a synagogue and adjacent kosher restaurant, though guards block me from entering the complex. Continuing along historic Jew Street, I presently came to another massive grey temple, the nineteenth century Brodsky synagogue. One of the few Odessa temples to survive Bolshevik persecution and destruction, Brodsky was similarly boarded up. Peering inside a gate, the premises looked desolate and forlorn, with a wary security guard standing watch.

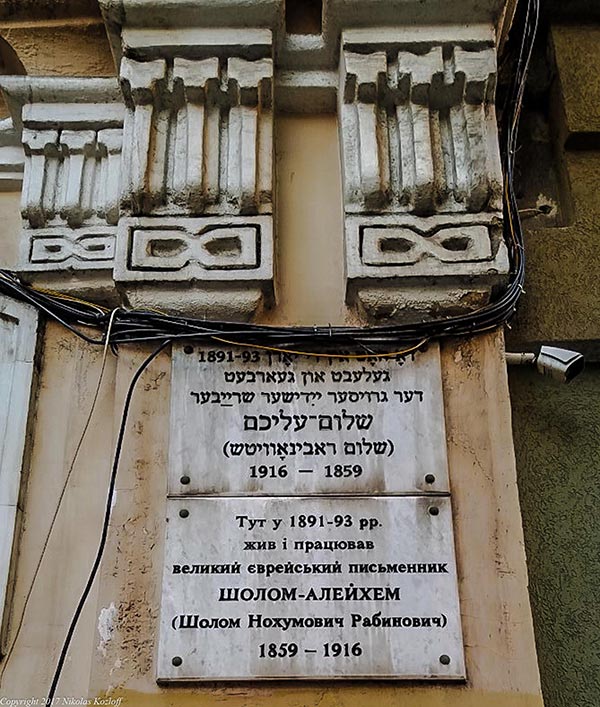

On another nearby street, I come upon a memorial plaque dedicated to legendary writer Shalom Aleichem, whose stories were turned into the stage and film musical Fiddler on the Roof. Like the Shalom Aleichem museum located in the town of Pereyaslav, which I had the opportunity to visit two years earlier, this spot is modest. Peering inside a dilapidated courtyard, one would never know this apartment block was once the home of a giant of Yiddish literature. In 1890, having gone bankrupt, Aleichem and his family were forced to give up their bourgeois apartment in Kyiv and adopt more modest living quarters in Odessa. Babel, who represents a later generation of Jewish writers, turned one of Aleichem’s novels about old shtetl life into a screenplay.

Sensitive Debate over Collaboration

Babel and Aleichem’s Odessa, which was once a center of Yiddish culture, was largely wiped out by the Nazis and their allies during World War II and on a psychological level I’m interested to know whether society as a whole has come to terms with the Holocaust. There’s plenty of historical reckoning in order here, since some Ukrainians collaborated with the Germans in Odessa, just like at Babi Yar. Though at least half of Odessa’s Jewish population managed to flee the city in advance of the arrival of Axis troops in 1941, between 80,000 and 90,000 remained. In short order, occupying Romanian troops ordered 19,000 Jews to assemble in the harbor area where they shot and burned many victims alive. At least 20,000 others were taken to the Odessa ghetto of Dalnik where victims befell a similar fate.

Romanians weren’t the only culprits, however: throughout the fall of 1941, Einsatzgruppen death squads worked in tandem with the German and Romanian militaries, as well as Ukrainian auxiliary police and local ethnic German recruits, to massacre some thirty five thousand Jews in Odessa. Occupying forces herded Jews not only to Dalnik but also relocated residents to another Odessa ghetto called Slobodka. However, Jews were not even given their allotted two days to move out; instead, they were promptly evicted while neighbors stole anything they could get their hands on. In January, 1942 Odessa’s streets were filled with the tragic sight of Jews making their way to Slobodka. Along the route, victims were reportedly harassed “by soldiers and local hooligans who, from time to time, grabbed parcels from the moving crowd and jeered, ‘You won’t need this anymore.’” Within Slobodka itself, locals hardly treated the Jews much better. Indeed, market vendors and non-Jewish folk in the suburb gouged Jews by pushing up the price of food. Other Jews were deported to the small township of Domanevka, where Romanian gendarmes and local Ukrainian police killed survivors.

Prior to the war, Jews made up the most populous demographic group in Odessa and as late as the 1930s, the city sported a Yiddish faculty at a local university; a Yiddish pedagogical college; many Yiddish schools and kindergartens; a Yiddish theater and a Jewish museum. By February, 1942 however, almost all of Odessa’s Jews had been deported from the ghettoes or killed, leading the authorities to gloat that the city had become “Judenrein” or “cleansed of Jews.” The occupiers were so thorough that they literally left no stone unturned: even tombstones in Odessa’s old Jewish cemetery were ripped off and shipped to Romania, where the material was sold to stonemasons. By war’s end, only 5,000 Jews remained alive in the city.

Odessa Reckons with the Holocaust

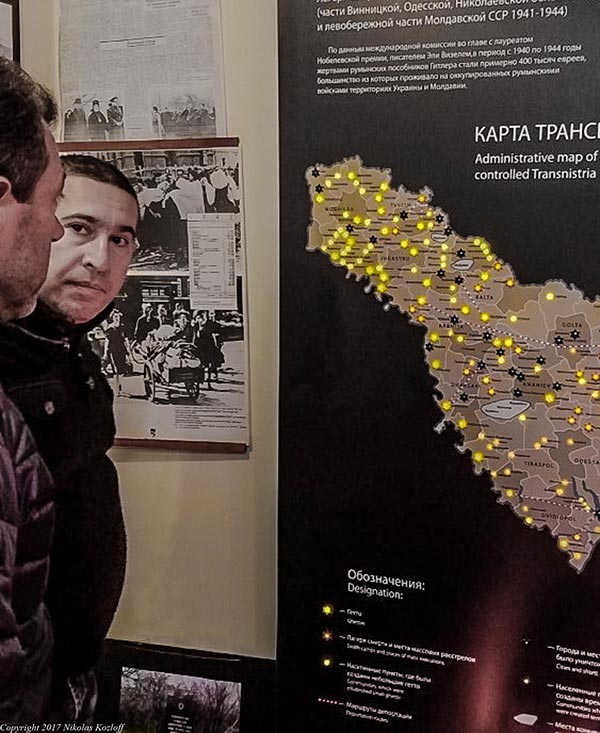

If Kozlenko has his way, Odessa will indeed come to terms with its past. As he gives me a personal tour of the local Holocaust museum, which not only documents wartime atrocities but also gives a revealing glimpse into Jewish life of the time, the director remarks “Before, people in Odessa didn’t know about this history but now people are becoming aware of the museum.” The facility also conducts local outreach by speaking with school teachers, who in turn spread information to children. Kozlenko adds, “Everything you see here has come about due to support from private groups rather than the government.”

Kozlenko himself got involved in the museum project back in 2006, when he received a call from a ghetto survivor who sought help and advice on publishing a book about Ukraine’s Balta concentration camp. The two volume book, which is titled Remember and Tell, came out three years later. The collection recounts the experiences and memories of Balta survivors and features previously unpublished photos. The book also contains documents which shed light on the Jewish experience during the occupation of Balta and Transnistria, also known as Trans-Dniester. As Kozlenko started to research the topic of Transnistria, he started wondering about his own family and discovered that many of his relatives had died in the ghetto. According to Kozlenko, only about 2,000 Jews survived Balta.

From Soviet Era to Independent Ukraine

Though Kozlenko and others have certainly helped to raise consciousness on the Holocaust, there are troubling signs that Odessa may have a long way to go before it overcomes its historical legacy. In the post-war Soviet period, Odessa was known for anti-Semitism which some claim was more pervasive than in other large cities. Experts claim that during the Soviet period, local residents as well as authorities failed to identify or disclose the location of World War II massacre sites around Odessa. In the 1970s, many Jews started to emigrate to Israel and the United States, particularly Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, which has come to be known as “Little Odessa.”

In newly-independent Ukraine, anti-Semitism has similarly continued to persist on certain levels. In plain view of Jewish klezmer festivals in Odessa, passers-by reportedly belt out anti-Semitic epithets. Meanwhile, Jewish leaders have accused local authorities of trying to hide the existence of a Holocaust mass grave located in a village about 100 miles from Odessa. The site was finally uncovered, but only in the midst of construction work on a gas pipeline. The mass grave, located on top of a concentration camp, had been set up by Romanians and German Nazis. In all, some 5,000 Jews died at the camp, most from starvation and disease.

Odessa Vandalism

What’s more, in a nod to previous tombstone vandalism of World War II, unidentified vandals broke into a Jewish cemetery in Odessa in 2007 and defaced more than three hundred graves as well as a Holocaust memorial. For good measure, the vandals painted red swastikas on the graves and monument while inscribing the message “Happy Holocaust” on the memorial, which is located on a spot where the Nazis killed thousands of Jews. Three years later, Kozlenko remarks, vandals scrawled a swastika on the Holocaust memorial once again.

The vandalism has proved unrelenting: in 2014, Odessa assailants again defaced the Holocaust memorial, a wall of the Jewish cemetery and the fence of a synagogue. Vandals scrawled swastikas, SS symbols and the message “Death to the Jews” on the properties (such ongoing vandalism has been a problem not only in Odessa but also at Kyiv’s Babi Yar). Kozlenko says the vandals scrawled the face of a pig on the Holocaust memorial. Tags on the graffiti indicated the vandalism had been the handiwork of none other than Praviy Sektor or Right Sektor, an ultra-nationalist political party. Needless to say, however, Right Sektor denied it was behind the vandalism and the authorities have failed to apprehend the culprits. “No one knows who did it,” Kozlenko remarks ruefully.

Odessa Eyewitness

To be sure, the outlook for Odessa’s Jews isn’t altogether pessimistic. In an encouraging sign, Kozlenko reports that 80% of the people who visit his Holocaust museum are non-Jews. Buoyed by the success of his museum, Kozlenko seeks reconciliation rather than confrontation with wider society. While he certainly disapproves of Kyiv municipal authorities, who recently moved to rename a street in honor of controversial World War II nationalist Stepan Bandera, Kozlenko believes “it’s not the right time to bring this question on the table. We want to bring people together. Maybe in future we can sit down and put this puzzle together and figure out what happened yesterday” (Kozlenko says that some nationalists also seek to rename Soviet-era streets in Odessa, just like their counterparts in Kyiv).

Kozlenko confides that he and his museum staff have installed metal guards on the windows, as well as a huge video camera in the front yard. You can never be too careful, he remarks, adding that “Someone can come from around the corner and hit you out of the blue.” Back in Kyiv, I had been struck by brazen Praviy Sektor flags fluttering out in the open without any awareness that this might cause offense, and unfortunately Kozlenko confirms that such displays occur in Odessa as well. “I’m concerned about this,” Kozlenko says. “People here are poorly educated and don’t have enough food, so they walk down the street with these flags without thinking about it.” Kozlenko is worried about such right wing nationalism, but on the other hand he’s not certain who’s specifically behind all the local anti-Semitic mischief. Perhaps Praviy Sektor could be responsible, but on the other hand the situation is murky and “It’s difficult to say who represents whom,” he says.

Odessa’s Legacy

Across town in a local café, I meet up with Denys Yacovlev, a professor of political science and sociology at Odessa National University. Right wing nationalists have been getting stronger throughout Ukraine, he says, and Odessa is no exception. “Ukraine is a modern western country,” he says, “but we have been in the midst of an economic crisis for no less than twenty years now. This encourages certain forces, such as nationalist groups, to try and capitalize on economic malaise for political purposes.”

For a further view, I head to Babel’s old Jewish quarter of Moldavanka to speak with Sergei Ischenko, a local journalist. Are people in Odessa aware of pogroms and anti-Semitic history, I ask? “Most people aren’t educated about this,” he says. “There is a myth about Odessa, as a multi-cultural and tolerant city devoid of strife and pogroms. And we want to think it is the case! There are no programs on TV about this, or articles in the newspaper. We don’t want to remember these types of incidents.”

Leave a comment