Ukraine: Still Failing on World War II

Judging from events, Ukraine has even now failed to come to terms with the legacy of the Second World War. Recently, spectators in Kiev were graced with a divisive sight: outside parliament, protesters clashed with police after legislators failed to support a bill recognizing the Ukrainian Insurgent Army or UPA. The bill in parliament would have restored “historical justice” and paid respect to the group. The UPA was a military offshoot of a group associated with Ukrainian nationalist Stepan Bandera, a historical figure who continues to stir controversy. Indeed, Bandera sought to make Ukraine into a one-party fascist dictatorship free of other ethnic minorities. Within the historical context of the 1930s this primarily meant forcible removal of Poles from Ukrainian territory.

During World War II, the UPA emerged as a nationalist guerrilla outfit which battled Soviet, Polish, and Czech forces in the name of independence. However, at one stage during the conflict the UPA also cooperated with the Nazis. Indeed, when Germans entered the western Ukrainian city of Lviv in June, 1941 Bandera’s nationalists joined Nazi Einsatzgruppen in carrying out pogroms against the Jews. By war’s end, it was said that both organizations which had been led by Bandera, that is to say the UPA as well as the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), engaged in atrocities against Poles, Jews and others.

A Divisive Debate

In light of such history, one might think the UPA would have little place in modern day Ukraine. Yet rightists are not easily dismissed: reportedly between 8,000-10,000 people showed up for the Kiev protest, which at one point turned violent as militants threw smoke and flash-bang devices at the authorities. Somewhat ominously, Ukrainian television showed protesters brandishing banners of the right wing Svoboda Party, which seeks historical recognition for the UPA. In the midst of war against Russian separatists in the east, some members of Svoboda have embraced Bandera, who was eventually killed by the KGB, as a nationalist figure.

It’s unclear what other Ukrainians makes of such foolishness, yet there’s some indication that mainstream political figures are hedging their bets. Beset by a serious military challenge in the form of Kremlin-backed Russian separatists, President Petro Poroshenko has stated that the “timing is good” to define the status of the UPA and the politician even signed a decree establishing a “Day of Ukrainian Defenders” on October 14. The date is significant as it marks the anniversary of the UPA’s formation [somewhat problematically, October 14th also marks the “Day of Ukrainian Cossacks”]. While Poroshenko has admitted that granting historical recognition to the UPA is divisive, he remarked on Twitter “UPA soldiers – an example of heroism and patriotism to Ukraine.”

Coming to Terms with History

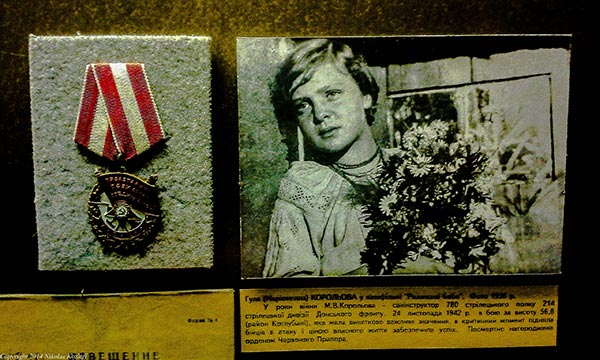

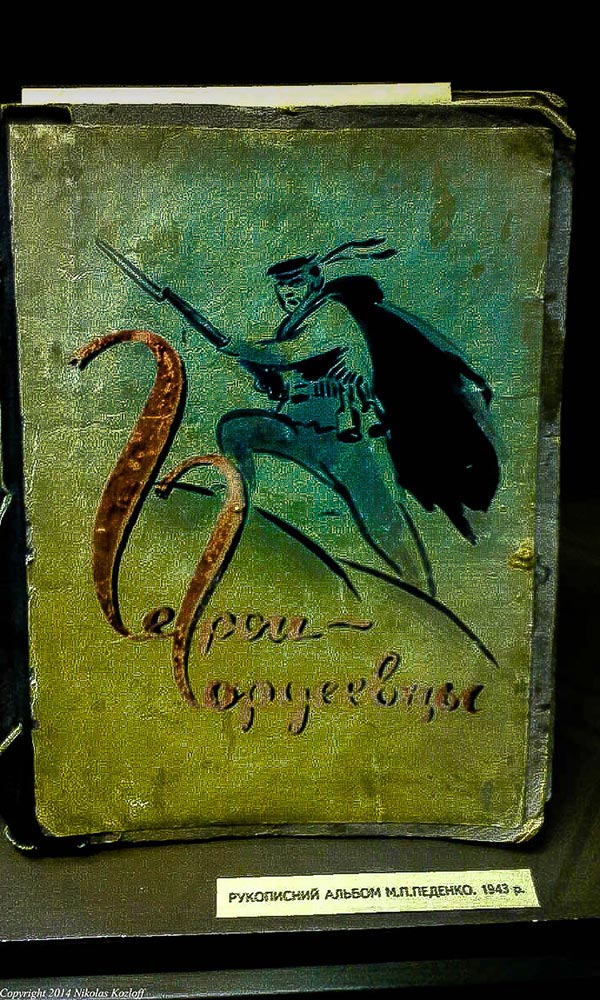

To this day, Ukraine continues to wrestle with its wartime past. In Kiev’s Museum of the Great Patriotic War, visitors are greeted with displays of Soviet military insignias and medals awarded to courageous fighters who battled Nazi Germany. Travel outside the capital and one hears similar stories of valor. Pereyaslav, a town located some 60 miles south of Kiev, was once a flourishing home to Jewish culture. During World War II, however, local Jews were subjected to atrocities. Tsylya Meirovna Gechtman, a local historian, says the Germans executed members of her family. Fortunately, she adds, some local Ukrainians hid Jewish peasants from the Nazis.

How does one square such history with the decidedly mixed legacy of Bandera? To be sure, Bandera collaborated with the Nazis though he was also later imprisoned in a German concentration camp. Indeed, Ukrainian nationalist goals were not identical to the Third Reich’s. While Bandera’s followers were responsible for murdering Jews, their ideology wasn’t entirely anti-Semitic but rather pro-Ukrainian. That is to say, they wanted their opponents out of the way and saw many local Jews as pro-Soviet. Some Bandera veterans survive even to this day, which makes it doubly confounding for many to come to terms with history.

Sifting Through Bandera Legacy

Anton Shekhovtsov, an expert on the European far-right and a research fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna, says history textbooks from central or western Ukraine make no mention of the fact that members of Bandera’s movement were involved in the Holocaust or pogroms in Lviv. Rather, he adds, Bandera is blandly described as a national liberation fighter. On the other hand, Shekhovtsov adds, “Bandera has been glorified not because he was an anti-Semite but because he was a nationalist figure who fought against Soviet influence. When people glorify him, it doesn’t mean that they are aware of this dark history or even endorse anti Semitism.”

Josef Zissels is General Council Chairman of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress in Kiev’s Podil neighborhood, a former Jewish quarter. He says the majority of the UPA did not take part in anti-Jewish executions. Mostly, he says, it was the Germans who committed atrocities along with local police units comprised of many different ethnic groups including Ukrainians, Belarussians, Russians and even some Muslims. “There’s almost no connection between Bandera and present day Ukraine,” Zissels remarks matter-of-factly.

Denis Pilash, a leftist political activist, is more concerned about Bandera’s historical legacy and links to present day politics. To be sure, he concedes, Bandera served time in a concentration camp and did not coordinate wartime atrocities directly. However, Pilash adds, “when you highlight the fact that Bandera was imprisoned, this serves to ignore” other inconvenient truths. Whether he was a fascist, an “integral nationalist,” or “proto-fascist,” Bandera was a far right totalitarian figure who opposed sharing political power with Poles, Russians and Jews.

It is dispiriting, Pilash says, that many young Ukrainians still look upon Bandera as a national hero. In general, he says, there’s a consensus in the wider society that Ukrainian nationalism has always been emancipating. What you wind up with, Pilash says, is a “very ethno-centric view” of the past which doesn’t help to promote the notion of a truly multi-ethnic society. “Many people,” he says, “including liberals, whitewash the history of the OUN. If you say Bandera is a fascist today, people think you are some kind of Moscow propagandist.”

Bandera’s Current Relevance

So just how much of a concern is the cult of Bandera? To be sure, rightist political parties such as Svoboda have recently fared poorly at the polls. Nevertheless, mainstream political circles seem unwilling to take on the nationalist right and Bandera symbolism. Indeed, during Maidan protests against the government of Viktor Yanukovych, UPA flags were clearly visible and demonstrators embraced a UPA battle cry which has now been stripped of its fascist connotations. In Lviv meanwhile, a local speakeasy features waiters dressed in olive partisan uniforms and UPA insignias.

Enmeshed in a deadly struggle with Russian separatists, many Ukrainians are seeking to fashion their own nationalist ethos. While that is somewhat understandable, Bandera is a poor model. Seventy years after the end of World War II, Ukrainians must eschew such symbols and look elsewhere in the search for a national identity.

Leave a comment