Note to Ukraine: Time to Reconsider Your Historic Role Models

In the midst of tumultuous political and social ferment, as well as escalating military conflict with Russian-backed separatists, Ukraine is casting about for a national identity. What are the country’s relevant values and symbols? As a relatively new and independent nation, Ukraine is seeking to answer such profound and pressing questions. The recent Maidan revolution, which in many ways highlighted Ukrainian nationalism, has only served to accentuate Ukraine’s deep psychological soul searching.

As the country seeks to sort out the post-Maidan milieu, Ukraine must also wrestle with its thorny political history. Who are the most important historic role models worthy of praise and emulation? At this point it’s too early to say who will win this contested battle over Ukrainian history. Unfortunately however, Ukraine seems to have elevated more conservative and right wing historic figures while neglecting or even obliterating the memory of its own liberal and more radical leftist past.

Still Failing on World War II

A recent article in the Daily Beast illuminates such controversial debates. In Kiev, a local museum has showcased plaster impressions or so-called “death masks” to commemorate Ukraine’s most famous figures. The curator has included busts of the ignominious Symon Petliura, a mediocre leader of Ukrainian independence during the country’s war of independence following the Russian Revolution of 1917, as well as Stepan Bandera, a highly controversial anti-Soviet fighter.

During recent Maidan protests which toppled President Viktor Yanukovych, a politician who had sought to move Ukraine into Moscow’s orbit, some protesters brandished posters of Bandera, a historic figure who resisted Russian encroachment. But while Bandera may have fought against the Soviets, some of his followers also collaborated with the Nazis during World War II, a fact which has served to tarnish the independence fighter’s historic legacy. Today, political parties of the far right glorify Bandera while some even brandish Nazi insignia [for a full explanation of such curious symbolism, see my earlier article here].

While such forces hardly constitute the majority in Ukraine, mainstream society and governing elites have failed to take a strong stand against extremism. Even worse, Kiev seems to be openly encouraging a kind of historic revisionism on World War II. Recently, President Petro Poroshenko signed a series of laws which were shuttled through parliament without even being publicly discussed. The legislation seeks to cultivate a sense of politically correct historical memory, and outrageously threatens those holding alternative views with whopping prison terms of up to ten years.

Kiev Political Elites Cave to Far Right

Writing in the New Republic, Rutgers historian Jochen Hellbeck notes that one of the new laws condemns both Communist and Nazi regimes of the past, as well as their symbols. However, the law mostly focuses on the Soviet era while ignoring atrocities committed against the Jews, “let alone the participation of Ukrainians in these atrocities.” Hellbeck writes that “the omission is strategic,” since another law actually glorifies partisans affiliated with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army or UPA, who collaborated with the German Wehrmacht. In 1943, when the Germans fled from Ukraine, many local policemen who had collaborated with the Nazis joined the UPA while committing atrocities against ethnic minorities. One UPA commander, Roman Shukhevich, espoused anti-Semitic beliefs and recently his grandson proved instrumental in helping to pass the new legislation.

The political ramifications of such developments are unfortunately plain for all to see. Recently, veterans of the UPA were invited to a VE-Day celebration in Kiev and were openly cheered by spectators. The Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, based in the nationalist western city of Lviv, played a key role in choreographing the proceedings. President Poroshenko himself presided over the event and addressed the soldiers. However, Poroshenko failed to mention anything about Ukrainian Jews during his speech.

Reaction within the scholarly community to such developments has been decidedly mixed. One group of academics and Ukraine experts wrote an open letter to Poroshenko, regretting that the new law would make it a crime to question the legitimacy of an organization (UPA) that slaughtered tens of thousands of Poles in one of the most heinous acts of ethnic cleansing in the history of Ukraine.” On the other hand, some historians have apparently turned their back on free speech, preferring instead to leave such contentious debates until the end of the war with Russian-backed separatists. Hellbeck, however, disagrees with such positions. “Nationalistic narratives of suffering and struggle against external enemies have great mobilizing power, particularly in times of war,” he writes. “Left unchecked, they will only intensify and perpetuate the war.”

Some Bright Spots

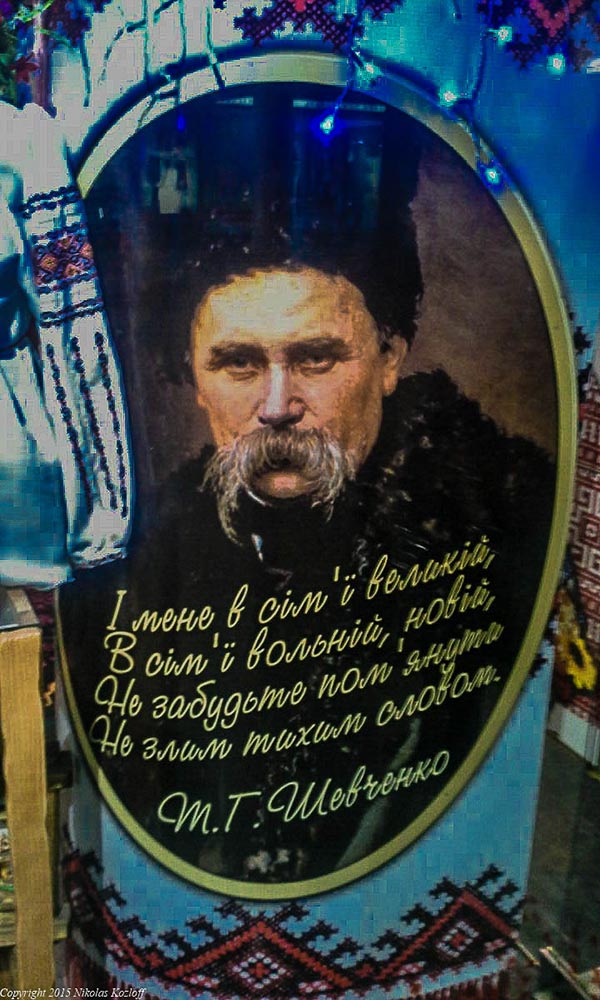

Though some have championed retrograde figures such as Bandera, there are fortunately a few bright spots. Taras Shevchenko, a prominent nineteenth century poet, has become an icon and symbol of national pride in Ukraine. For many, Shevchenko carries just as much stature as Shakespeare in England. Shevchenko’s poems are inextricably linked to his own harsh life: born a serf, he was later freed from bondage. Politically, Shevchenko advocated the abolition of serfdom as well as Ukrainian independence. Shevchenko’s poems, which were written in Ukrainian, criticized Russian oppression and drew the attention of Czarist authorities. As a result, Shevchenko was arrested and banished to an army post.

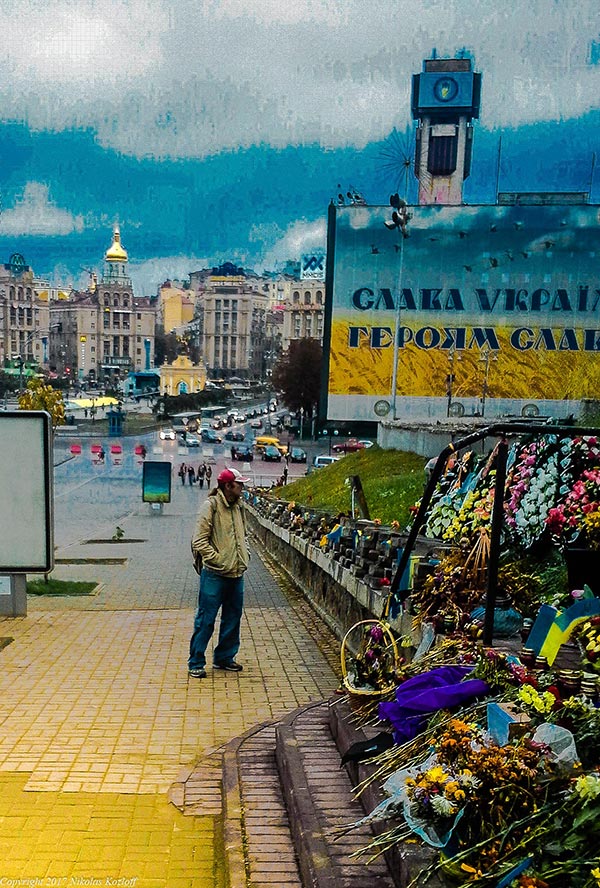

Because he was a fervent critic of Moscow, Shevchenko remains a convenient historic role model for patriotic Ukrainians in the current day milieu. Indeed, during Maidan demonstrations, protesters carved a wooden sculpture of Shevchenko near the square. The structure is one of many thousands of Shevchenko statues spread out all over Ukraine. After the fall of Yanukovych, the new government in Kiev hailed Shevchenko as an inspiration to the Maidan movement. In March, 2014 Ukrainians celebrated the bicentennial of Shevchenko’s birth. In Kiev, Maidan activists laid wreaths at his statue while others plastered the city with celebratory posters [to see a video of the proceedings, click here]. In Crimea, however, the commemoration was met with political strife as pro-Russian activists attacked Ukrainians near a local Shevchenko monument.

Ukraine’s Forgotten Leftist Nationalists

Extolling the virtues of Ukraine’s national icon is fine, though many seem to have forgotten the political radicals who followed Shevchenko. In an interview with New Left Review, Kiev-based sociologist Volodymyr Ishchenko discusses the recent politicizing of Ukrainian history. A founding editor of leftist Commons Journal, Ishchenko notes that “Ukrainian nationalism now mostly has these right-wing connotations,” and such emphasis “has clearly overpowered the leftist strands.” The sociologist adds that “when it emerged in the late nineteenth century, Ukrainian nationalism was predominantly a leftist, even socialist movement.”

Ishchenko points out that the first person to call for an independent Ukrainian state was a Marxist, Yulian Bachynsky, who wrote a book in 1895 called Ukraina Irredenta. Today, Bachynsky is little known amongst historians and political scientists, though he played a pivotal role in developing Ukrainian national consciousness. In 1899, when Ukraine formed part of the Russian Czarist Empire, Bachynsky co-founded the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party. In 1919, amidst subsequent political upheaval in his country, the activist traveled to Washington, D.C. There, he attempted to secure U.S. recognition for an independent Ukraine.

A Forgotten Legacy

What is Bachynsky’s significance in light of Ukraine’s current day politics? Perhaps, the political thinker would have been critical of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church and religious dimensions associated with recent Maidan protests against Viktor Yanukovych. Though he was the son of a priest, Bachynsky adopted stridently anti-clerical positions. Furthermore, in light of the rise of so-called “oligarchs” in the post-Soviet era, Bachynsky’s Ukraina Irredenta is worth re-examining. If he had been present during the Maidan revolution, Bachynsky would have undoubtedly approved of calls by protesters to rid the country of the oligarchic elite. On cultural matters, too, Bachynsky was way ahead of his time: the political thinker argued that Ukraine ought to be a political and not an ethnically defined nation. At one point, he even remarked that Ukrainian independence should concern most everyone “no matter whether he is an indigenous Ukrainian or a Great Russian, Pole, Jew, or German.”

Despite his many contributions, Bachynsky is not widely remembered today. After he failed to secure vital U.S. recognition for Ukrainian independence, Bachynsky moved back to Ukraine. He was later arrested by the Soviets for his nationalist ideas, and died in a prison camp in 1940. In recent years, rightwing forces have sought to portray themselves as the more authentic guarantors of Ukrainian nationalism while obscuring the role of people like Bachynsky. In the western city of Lviv, for example, some extol figures like Bandera while conveniently forgetting that Bachynsky himself graduated from Lviv University’s Law School before he pursued a political and journalistic path.

Other Forgotten Icons

Speaking with New Left Review, sociologist Ishchenko is puzzled by Ukrainians’ one-sided view of history. Though there were other leftist nationalists besides Bachynsky, Ishchenko notes that “any attempts to revitalize socialist ideas within Ukrainian nationalism today have been very marginal.” Hopefully, more people will become aware of the contributions of Mykhailo Drahomanov, one of the premier figures of Ukrainian civic, scholarly and cultural life during the late nineteenth century. A political radical, Drahomonov sought to create a sense of pride amongst the peasantry by publishing books in his own native Ukrainian language. Drahomonov published on a wide array of topics, including Ukrainian folk literature and music. After the Czarist authorities dismissed him from Kyiv University, Drahomonov went into European exile and the scholar published a number of pamphlets seeking to alert public opinion to the plight of Ukraine under political autocracy.

Like Bachynsky, Drahomonov was a socialist and espoused anti-clerical beliefs. In certain respects, however, the academic cultivated a more visionary system of politics. An admirer of the anarchist thinker Proudhon, Drahomonov envisaged a Ukraine which was free of authoritarian influences. However, Drahomonov was far from parochial and thoroughly disliked xenophobic strands of Ukrainian nationalism. In fact, the academic favored close cooperation amongst all ethnic minorities within Ukraine, including Jews. Drahomonov furthermore endorsed the right of minorities to develop their own cultural autonomy, and he was the first nationalist leader to visit the ethnically diverse western region of Transcarpathia. Given the sheer breadth of his writing and contributions, one would think that many would seek to restore his legacy. However, according to local media, “Drahomanov is still little known and undervalued by his own nation in the new Ukrainian state.”

Questionable Perspective on Civil War

Such selective historic amnesia is also apparent when it comes to the treatment of Ukraine’s civil war period from 1917-1921. Recently, the Ukrainian Consulate in New York held a ceremony commemorating historical figures including the infamous Pavlo Skoropadsky, a reactionary descendant of an 18th century Cossack hetman. During the proceedings, dignitaries displayed a bronze bas-relief of Skoropadsky, an individual hailed by the Ukrainian government as a “strong leader” and a “representative of famous Cossack family.”

Rather questionably, Ukrainian diplomats in the U.S. write that “despite the unfavorable circumstances triggered by the war and revolution, and the difficulties of the Ukrainian liberation movement caused by external political and especially military factors, the government of Hetman Skoropadsky had considerable achievements in foreign and domestic policy.” Going over the top, authorities add that “the policy of P.Skoropadsky was extremely effective and beneficial for the state. It was a real manifestation of Ukrainian patriotism and national consciousness.”

Short and Ignominious Rule

The political reality surrounding Skoropadsky’s rule is somewhat more sobering. A member of the landholding elite and a Czarist military general, Skoropadsky found himself at odds with the political milieu following the Russian revolution of 1917. Skoropadsky opposed the socialist policies of the new Central Rada (council) government in Kiev, including agrarian reform. Gathering together his fellow landowners, the general launched a coup against the Rada with the support of German military command. Then, for good measure, Skoropadsky assumed the illustrious title of “hetman of Ukraine,” a title which he hoped would become hereditary.

In short order, the Central Rada was dissolved and agrarian reform revoked. Censorship was imposed under the new puppet regime, and Ukraine’s social and economic policies were refashioned so as to reflect the interests of Germany as well as large local landowners and industrialists. Resistance to Skoropadsky rule took the form of rural uprisings, sabotage, strikes and even assassination of high up German military officials.

During his short and ignominious rule, Skorapadsky managed to alienate key constituencies including nationalists, socialists and the peasantry. When the Germans ultimately abandoned Kiev, the Skoropadsky regime collapsed and the general fled into exile in Germany. There, Skoropadsky cultivated the support of monarchists as well as the backward Junker class. In 1944, he lobbied the Nazis to release none other than Stepan Bandera from a concentration camp, suggesting that the two may have shared at least some similar political beliefs.

Mediocre Historic Leader

In the midst of political disarray, many within the Ukrainian underclass yearned for a more progressive government. What they got, however, was mediocre leadership in the form of Simon Petliura, a figure who would shortly launch Ukraine upon a path of further hardship. Petliura was a socialist member of the Central Rada, which had earlier been dissolved by Skoropadsky. When the puppet regime collapsed in Kiev, Petliura became leader of a five-member directorate of the Rada and also assumed the title of “ataman” or commander-in-chief of the army.

To be sure, Petliura’s task was challenging as he confronted not only Soviet forces but also anti-Bolshevik White Russians. However, Petliura’s left-leaning government was soon marred by controversy for its handling of ethnic politics. Initially at least, Petliura offered autonomy to the Jewish population and even printed local currency in Yiddish. Shortly, however, Petliura’s name was marred amidst anti-Jewish pogroms in 1919. Some recent scholarship argues that Petliura personally ordered the worst of these pogroms, in which more than 1,000 Jews were killed. Typically, Ukrainian nationalist forces carried out the massacres under the pretext that Jews were Bolsheviks. Whatever the case, the Petliura government was either unable or unwilling to stem the violence.

In late 1919, the Soviets vanquished Ukrainian nationalists, and Petliura himself fled into exile in Paris. Several years later, the former leader was fatally shot by a Jew who claimed to be avenging the infamous earlier pogroms. Somewhat incongruously, Ukrainian president Yushchenko laid a wreath on Petliura’s gravesite in 2005. More recently, the Kiev City Council even decided to rename a local thoroughfare as Simon Petliura Street. Writing in the Jewish Daily Forward, historian David Fishman says Kiev should be commended for the “totality of Ukrainian-Jewish co-existence.” However, he adds, “truth be told, Ukrainians have not honestly confronted the dark side of their history. In order to mend Ukrainian-Jewish relations, Ukrainians need to have the courage and self-confidence to honestly confront the anti-Semitism of their past.”

Obliterating Ukraine’s Revolutionary Past

Even as they emulate undesirable historic role models, many Ukrainians forget idealistic and more progressive leaders. As they hark back to the civil war period, Ukrainians may want to take a second look at Nestor Makhno, an anarchist revolutionary who fought against the forces of reaction. Born into the peasantry, Makhno later joined a local anarchist group and became a kind of Robin Hood-style bandit, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. Arrested by the Czarist authorities, Makhno later turned into a voracious reader in jail and received the political education which had earlier eluded him. Amidst revolution in 1917, Makhno was freed and amazingly the bandit revolutionary managed to consolidate a free state in southeastern Ukraine.

In an effort to free the peasantry and cultivate a system of self-governing communes, Makhno audaciously took on not only Bolsheviks but also the conservative White army, occupying German and Austrian forces and even the authorities in Kiev. Unlike Petliura, Makhno took a strong stand against anti-Semitism and some claim that anarchist forces were much better than other rival armies in this regard. Fighting under their characteristic black banner, Makhno’s guerrilla forces launched covert raids, distributed goods to the peasants and managed to gain the trust of the local population. Eventually, however, Makhno was overwhelmed by the Bolsheviks and was forced into exile, having failed to secure his dream of a truly independent anarchist Ukraine.

Voyage to Kiev

Of all the historical figures swirling around the Ukrainian Civil War, Makhno is arguably the most worthy of praise. Yet oddly, Makhno’s legacy has been somewhat marginalized. That, at least, is the impression I get from speaking to Denis Pilash, a leftist political activist living in Kiev. Late last year, I spoke to Pilash about Ukrainian nationalism and the country’s curious search for historical identity. To be sure, Pilash tells me, Makhno is highlighted in popular culture every so often. What is more, the revolutionary is a great symbol and represents the notion of being able to rise up against any government and overthrow authority. In this sense, Makhno reinforces tough and sturdy myths about the Ukrainian character. Unfortunately, however, many Ukrainians have “no deep understanding” of the anarchist’s political movement.

Recently, Makhno’s home town celebrated the revolutionary’s 125th birthday, though the event was reportedly a “relatively muted affair” and there was no nation-wide remembrance. Speaking with New Left Review, sociologist Ishchenko remarks that “the right has worked to reinterpret figures such as Makhno along nationalist lines–not as an anarchist, but as another Ukrainian who fought against communism. In their eyes communism was a Russian imposition, and anarchism too is depicted as ‘anti-Ukrainian'” Pilash agrees, adding that Ukraine’s leftist history has been largely forgotten and therefore he and his colleagues must “rescue” figures like Makhno amidst Ukraine’s contentious and ongoing debates over the course of its political past and future.

Leave a comment