Note to Ukraine: Time to Reconsider Your “Cossack” Pride

Confronted with an existential threat in the form of Vladimir Putin, Ukraine is embracing patriotism and, in some cases, nationalist symbolism. In Ukrainian consciousness, the notion of the “Cossack” looms large, and during recent protests against the unpopular government of Viktor Yanukovych and subsequent drive to war with Russian separatists, many have fallen back on somewhat questionable historical associations. Indeed, traditional symbolism was very much apparent at Kiev’s Maidan Square during the revolt against Yanukovych, with some nationalist protesters even sporting Cossack-style costumes and hairstyles. In the wake of the Maidan, the National Art Museum has been instilled with a sense of pride and stocks display cases full of ethnic artifacts such as Cossack musical instruments.

So just who were the Cossacks and why are they assuming so much political importance in present day Ukraine? While their origins are somewhat obscure, many historians believe Ukrainian Cossacks first formed military societies in the 14th and 15th centuries. Over the subsequent two centuries or so, Cossack peasants refused to submit to Polish or Russian rule. Rather than live under tyranny, they migrated to the undeveloped Ukrainian south where they established paramilitary settlements. Out on the steppe, Cossacks hunted, fished and gathered honey. Their numbers were constantly buoyed by other peasants, adventurers and even nobility. Cossacks, then, were originally fugitives from serfdom and feudalism and indeed, the word “Kazak” is derived from the Turkic term “Kazaky,” or free person.

By the mid 16th century, the Cossacks had developed their own democratic political system based on a general assembly (rada). Over the next hundred years the Ukrainians, who were championed by a Cossack horde, drove out Polish overlords with assistance from the Tatars. Eventually, the Cossacks unified to form a group called the Zaporozhian Host, named after the capital of their pseudo-state at the town of Zaporozhska Sich [meaning armed camp of the lower Dnieper].

Freedom Loving Horde to Czarist Shock Troops

Sounds romantic and even heroic at times, though the Cossack role in Ukrainian history is hardly what one might call blemish-free. In the 17th century, anti-Semitism flourished and many lower class Ukrainians, including Cossacks, accused the Jews of working on behalf of wealthy landowners. As they rose up against their Polish rulers, the Cossacks also turned against the Jews. In so doing, Cossacks seemed to take on a new backward identity. Indeed, the original Cossack hosts in Ukraine had been multi-ethnic. Josef Zissels, General Council Chairman of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress in Kiev, remarks “there were a lot of Cossack movements, and there were Jews involved in such movements and some were even leaders of squads and divisions.”

During the Chmielnicki massacre of 1648-1649, Cossacks killed around 100,000 Jews and many communities were utterly destroyed. Cossack cruelty was so systematic that many Jews chose to flee and be sold into slavery by Crimean Tatars. Eyewitness accounts speak of Cossacks ordering Jews to dig their own graves and burying women and children alive. As horrible as this period was for Jews, subsequent conditions failed to improve. Though the Zaporozhian Host briefly existed as an independent state, the Cossacks were obliged to swear allegiance to Russia in 1654. Eventually, Cossack horsemen came to serve as the Czar’s Special Forces. What is more, Cossacks participated in violent pogroms against Jews, meaning attacks accompanied by destruction, looting, murder and rape.

In the eyes of the Bolsheviks, Cossacks represented a backward order which needed to be stamped out. That’s somewhat understandable, given that Cossacks supported pro-Czarist forces after the 1917 Revolution and subsequent civil war. In 1919, the Bolsheviks pursued a process of “decossackization,” which authorized local parties to target wealthy Cossacks. In a vengeful act of fury, the Bolsheviks killed between 300,000 and 500,000 Cossacks. Those who were not eliminated were deported to other regions of the Soviet Union.

Cossack Revival

Not surprisingly, authorities discouraged traditional Cossack culture throughout the Soviet period. With the emergence of an independent Ukraine, however, many have fallen back on the nation’s earlier past. Those Ukrainians who read are surely aware of dark Cossack history, though many others may simply see Cossacks as colorful and merry folk from the countryside. Back in Kiev, however, Zissels takes a somewhat more nuanced view. To be sure, he declares, Cossacks took part in anti-Jewish pogroms. On the other hand, he declares, French crusaders committed all types of abuses, but that does not necessarily imply that contemporary French society has a medieval outlook.

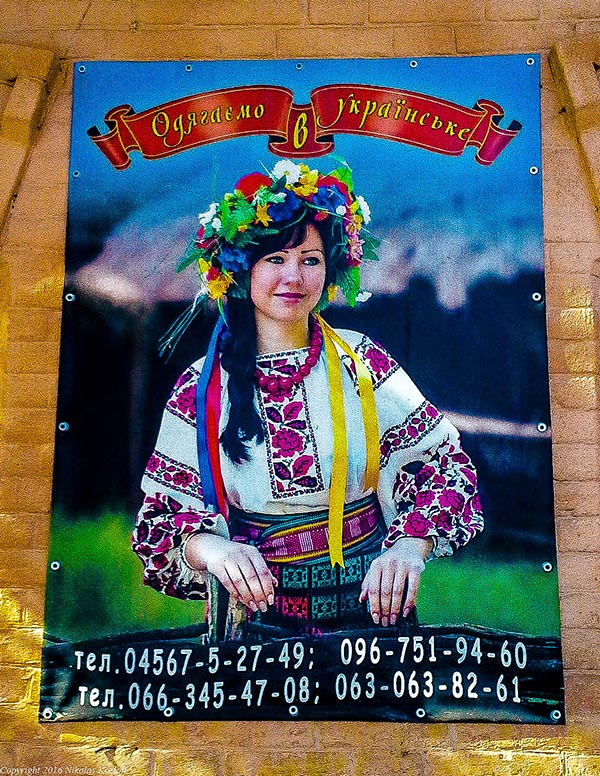

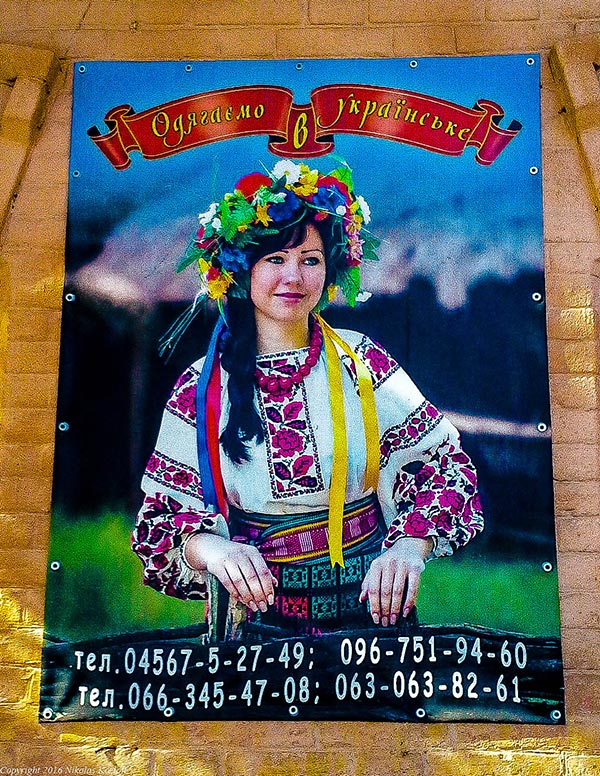

So, just what are we to make of the new Cossack mythology? Certainly, modern self-styled Cossacks are more likely to collect folk music than to be carrying out pogroms. Displays of traditional Ukrainian folklore and clothing have proliferated meanwhile, all of which seem rather harmless. According to Tetiana Bezruk, a researcher at the Congress of National Communities of Ukraine, local businesses selling such wares are more visible since last year’s protests and the eruption of war against Russian separatists in the east.

On the other hand, during the revolt against Yanukovych, Ukrainians employed historic symbolism which to the outside observer might have seemed a little odd. For instance, people referred to the Maidan protest area in Kiev as a Cossack “Sich.” Furthermore, Ukrainians sang the national anthem at Maidan which ends on the words “we, brothers, are of the Cossack nation.” Denis Pilash is a leftist political activist who took part in Maidan protests. As a member of the Rusyn ethnic minority, which hails from the western region of Transcarpathia, Pilash felt strange in the midst of such nationalist displays.

The risk of course is that in the midst of war Ukraine may fall back yet further on questionable nationalistic motifs. In Pilash’s home region of Transcarpathia, a group calling itself “Carpathian Sich” engages local youth and conducts “war games” in the forest. The political right, meanwhile, clearly would like to rescue Cossack history for its own purposes. Take for example the Svoboda party, whose leaders express a preference for “Cossack rock” music.

While it would be an exaggeration to argue that Cossacks have represented a wholly backward and malignant force throughout Ukrainian history, they are a highly dubious source of national pride, and that is putting it mildly. If Ukraine is to progress and consolidate its multi-ethnic democracy, it should eschew such symbols and search for far less problematic points of reference in the country’s historical past.

Leave a comment