Ukraine, Politics of History and Jewish Identity: A Personal Story

To the extent that Western media focuses on Ukraine at all, it tends to focus primarily on Kyiv’s war with Russian-backed separatists in the east of the country. Yet dig a little deeper and it becomes clear that Ukraine confronts many other significant problems that are frequently neglected or overlooked. Take, for example, the pressing need to protect and conserve a multi-ethnic, tolerant and pluralistic society. In the wake of popular protest at Maidan square that toppled the unpopular regime of Viktor Yanukovych, how will the new Kyiv government handle multi-ethnic politics in Ukraine?

Having recently conducted a research trip to Ukraine, I have my own perspective on these matters. Local political observers I spoke with were quick to point out that Maidan was a multi-ethnic movement, and though participants played some mediocre nationalistic music on the square, a Jewish klezmer band also performed on stage. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to refer to Ukraine as a country that is stirred by constitutional patriotism and civic mindedness rather than aggressive nationalism. Furthermore, judging from recent elections, the far right doesn’t seem to be a particularly viable threat. Nevertheless, it’s disturbing to see how mainstream society as well as political elites have glossed over or failed to condemn the far right, an ominous trend that ultimately serves to legitimize such groups.

Status of Ukrainian Jews

What are the implications of renewed Ukrainian nationalism for ethnic minorities and Jews? When many people consider the status of Jews in the country, they tend to hone in on very unflattering World War II history. At one stage of the conflict, some Ukrainian nationalists cooperated with the Germans and joined Nazi Einsatzgruppen in carrying out pogroms against the Jews. Though certainly horrific, one must be careful not to overgeneralize about Ukrainian society; it is one thing to read a book about World War II and another to assess modern Ukrainian Jewish life in the 21st century.

Indeed, it would seem that the 100,000-strong Jewish community is relatively well integrated into society and does not feel particularly persecuted. That, at least, is the impression I receive from talking with Josef Zissels, General Council Chairman of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress in Kyiv. During our interview, he remarked to me that there’s some anti-Semitic sentiment at the lowest rungs of society, “but in the mainstream and the top there’s no place for this type of thing.”

Ukrainian Jews in Midst of War

It’s interesting to speculate on how the recent war with Russian-backed separatists will affect the local Jewish community. Tetiana Bezruk, a researcher at the Congress of National Communities of Ukraine, said Jews identify as Ukrainians and many even support the war against Russian-backed separatists in the east. Zissels confirmed as much too, remarking that some Jews served in the Ukrainian army. He added that many Jews are patriotic and are driven by a visceral “phobia” toward Russia.

In a bizarre twist, it also seems that a few Jews have fought with the far-right Azov Battalion, one of the many volunteer outfits operating in the Ukrainian east. As I’ve noted in previous articles, the Azov Battalion is enthralled with nationalist symbolism, and fighters even sport certain Nazi insignia. But according to Zissels, “within Azov Battalion we have Nazis but also some Jews, including individuals holding Israeli passports. They all call themselves brothers.” When I expressed amazement and even incredulity at such developments, Zissels remarked, “I speak to Jews affiliated with Azov Battalion regularly, and they do not report any anti-Semitism. For the time being these people are collaborating. After the war, when it ends, we will deal with local Nazis on our own terms.”

Voyage to Pereyaslav

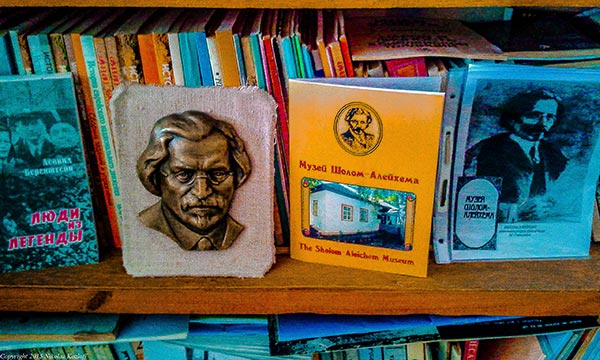

In an effort to gain more insight into Jewish life, I traveled to Pereyaslav, located some 60 miles south of Kyiv. The rural town was once home to Yiddish literary legend Shalom Aleichem (1859-1916) and the stage and film musical Fiddler on the Roof was based on his stories. Iryna Kucherenko, the director of the Shalom Aleichem museum, said the local Jewish community wasn’t too concerned with right-wing nationalism. Jewish women in Pereyaslav, she explained, want to support the Ukrainian war effort by helping provide soldiers with appropriate body armor. Kucherenko added for good measure that a Jewish battalion recently deployed to the front.

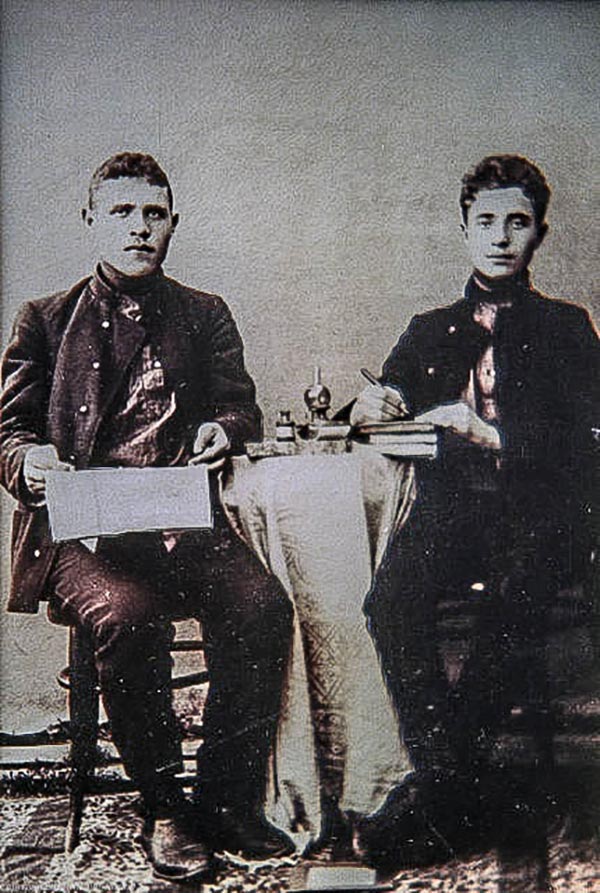

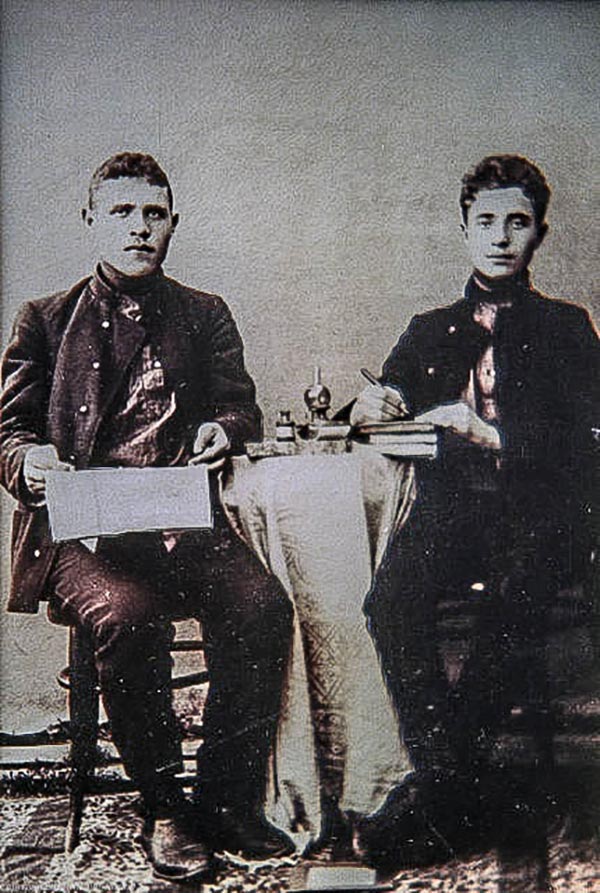

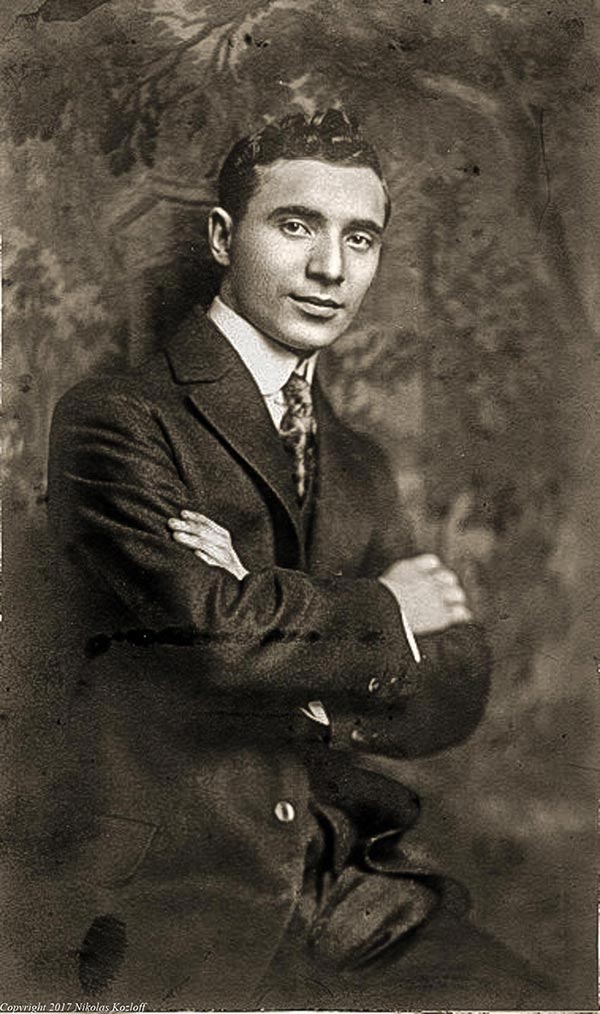

To be sure, I was interested in such history, but I also had my own personal motivations on this research trip. I went to Pereyaslav as my grandfather Josef Kozloff (1890-1954) was born and grew up in the town. The Kozloffs weren’t impoverished, though life was difficult in Pereyaslav, where the family worked in the local leather business and perhaps engaged in some farming on the side. In an early photo taken in 1905, Josef and his brother Nathan posed for the camera. The two were dressed in their finest clothes, with Nathan sporting handsome boots and Josef wearing a traditional tunic. A young man intent on displaying cultured manners, Josef sat next to an inkwell holding a pen.

Rebel Without a Hat?

Perhaps many Jews feel relatively well integrated into Ukrainian society today, but what about the longer historical record? Though it’s unclear whether Josef spoke Ukrainian, he personally referred to himself as such. However, my grandfather lived in Pereyaslav during the Czarist period, prior to official Ukrainian independence. I never met Josef, who died before I was born. My father, Max Kozloff, reported that his family was “unfamiliar with cosmopolitan aspects” of life. However, Josef knew how to write and “took great pride in his beautiful penmanship.” In the home, Josef spoke Yiddish, though my grandfather was also quite proud of his literate Russian.

From talking to local residents in Pereyaslav, I got the impression that ethnic identity might have taken on a multifaceted character during the Czarist period. Josef himself was imbued with a kind of rebellious spirit that went against tradition. According to my father, Josef “was very anti-religious and secular. In this sense he was somewhat atypical.” In a Jewish community center in Pereyaslav, I spoke with Tsylya Meirovna Gechtman, a local historian. When she saw the old photo of Josef and Nathan, she exclaimed, “They are not wearing hats, and this is inappropriate for them! Jews are supposed to wear hats. Maybe they weren’t Hassidic or Orthodox.”

Malleable Identities

Imbued with an atheistic spirit, Jews such as my grandfather may have eschewed religion while embracing Russian language and literature. What is more, Kozloff itself is a Russian surname. According to Kucherenko, many Jews assumed such Russian last names, and Czarist authorities encouraged mixed marriages. It was not uncommon, for example, to observe Ukrainian men marrying local Jewish women. Though officials never forced Jews to adopt Russian surnames, many embraced the custom simply out of fear or concern that they might fall prey to anti-Semitic attack or pogroms. However, if they were in a more trusting frame of mind, locals might also add their own Jewish name by writing it in brackets.

Though Jews were certainly subjected to anti-Semitism in Ukraine, it’s not as if they were gripped with constant fear. According to Kucherenko, many locals in Pereyaslav held stereotypical views about Jews, but “there was no discrimination.” In fact, within Pereyaslav, “Ukrainian and Jewish life was intertwined.” Russian was the common language of daily business in town, though some villagers also spoke Ukrainian. It is also possible people communicated in a kind of pidgin called Surzhik. (To this day, Jews at the local community center speak in this hybrid language.) There was no “ghetto” in Pereyaslav, and most Jews were able to achieve a kind of modest, middle-class respectability. Shalom Aleichem’s father, for instance, owned a small hotel in the area.

To hear Gechtman speak, Pereyaslav displayed a multi-ethnic character during Czarist times. At a local blacksmith’s shop, her own family employed a Ukrainian assistant who spoke Yiddish. At table, meanwhile, her grandfather was fond of reading newspapers aloud in Russian to anyone who cared to listen. However, within the household people were free to speak whatever language they pleased. Ukrainians and Jews lived together “in peace and harmony,” and there were 13 local synagogues in town. Meanwhile, Jews were free to work as tailors, blacksmiths, traders, shop owners, doctors, lawyers, teachers and even cab drivers. According to a website dealing with Pereyaslav history, Jews made up a full one third of the town’s population at the turn of the 20th century.

Past and Present of Ethnic Relations

What is the relevance of Pereyaslav’s multi-ethnic history for current-day Ukrainian politics? Sadly, many Ukrainians have little knowledge of their own country’s colorful past and tend to promote a rather monolithic and narrow-minded view of history based solely upon the Ukrainian ethnic experience. Perhaps it would be more productive to delve into the country’s rich interethnic experience so as to foster greater current understanding between Ukrainians and other minority populations.

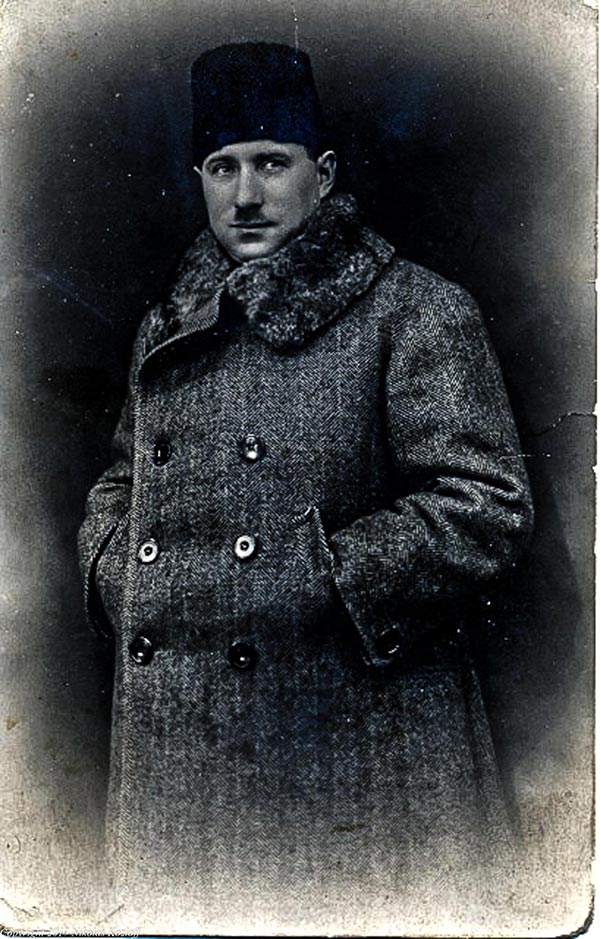

Furthermore, Ukraine should stop whitewashing the record and blaming Russia for all the country’s historic calamities. Though Pereyaslav was tolerant in certain respects, the town was far from an ideal home for local Jews, and many simply opted to emigrate. In 1910, for example, my grandfather Josef and his family traveled to Chicago, where they settled in a Jewish colony just south of the Loop. On an Ellis Island manifest, Josef Kozloff (or Kozlow) is listed as “farm laborer.” An ambitious and entrepreneurial man, Josef took to his new adopted country with gusto, rarely discussing or reminiscing nostalgically about life back in the Old World.

It’s not entirely clear why the Kozloffs chose to abandon Pereyaslav. For sure, the family would have sought greater economic opportunities abroad. Yet it’s hard to believe that politics did not play some kind of a role in the decision to leave for the United States. Would the Kozloffs and others have perceived Russia as the main threat to their existence, or rather rising Ukrainian nationalism? The question is somewhat complex, since Ukraine could be a tolerant place, though such peace was punctuated by sporadic violence. In another complex twist, Jews and Ukrainians formed part of the Russian Czarist empire at this time, and both were subject to repression.

Jews and Anti-Czarist Activities

Jewish perceptions of Russia may have been nuanced at the time. On the one hand, my grandfather Josef seems to have regarded Russian language, music and history as a sign of high culture. On the other hand, many Jews reviled Czarist autocracy and local repression within Ukraine. Alluding to the painful history of anti-Semitism, my father Max remarked, “I’m not sure if the family was victimized personally, but it would be hard to imagine Josef didn’t witness something.”

In 1905 Russia was engulfed in a wave of political turbulence. In the midst of war with Japan, revolution and anti-Semitic pogroms, Josef and his brother Nathan distributed anti-Czarist materials and were arrested for subversion. As Jews, meddling in such sensitive political matters took some courage. According to Kucherenko, more non-Jews were engaged in political activities in Pereyaslav than Jews, since the latter were afraid of pogroms.

In the end, Josef and Nathan were caught and supposedly lined up to face a firing squad. However, for some reason the execution was called off at the last minute, and the brothers were spared. There were other mortal dangers, though: Young men were subjected to the draft, and many resorted to extreme measures to avoid this fate. Nathan, for example, voluntarily tore his eardrum with hot metal so as to get out of military conscription.

Russians, Ukrainians and anti-Semitic Violence: 1881-1905

As the governing authorities at the time, Russian Czarist officials were most responsible for anti-Semitic violence. According to Kucherenko, state officials organized pogroms and did their utmost to blame the Jews for stirring up political trouble. Attackers would enter Jewish households, damage windows and property and try to force people out. Yet despite high levels of tolerance for, if not outright encouragement of, anti-Semitic violence emanating from the upper echelons of the Russian government, some Ukrainians too seem to have played a role in local riots.

In 1905 pogroms broke out all over Ukraine, including in the largest cities, such as Kyiv and Odessa. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, more than 800 people were killed in the violence. “The most prominent participants,” notes one historical article, “were railway workers, small shopkeepers and craftsmen, and industrial workers. The peasants mainly joined in to loot property.” It wasn’t the first time that anti-Semitic violence had swept through the region; in 1881, for example, the local governor-general in Kyiv turned a blind eye to severe anti-Semitic attacks. As violence spread, local officials and police did nothing to restrain rioters. Elsewhere, the local Ukrainian population took out their frustrations upon Jews, and “attackers came from among the rabble of the towns, the peasants, and the workers in industrial enterprises and the railroads.”

According to an entry in the International Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, Ukrainian pogroms continued until 1884. Anti-Semitic attacks of the era were perpetrated mainly by migratory and railroad workers. However, the local population “passively observed the plunder and violence and left the mobs unhindered, seeing these pogroms against an unloved minority as a suitable release for the pressures of unresolved social issues.”

Russians, Ukrainians and Jews: Revolution to Civil War

Just where does my own family stand in relation to such history? From talking to local experts, I got the impression that inter-ethnic relations weren’t terrible in Pereyaslav. However, I always wondered why my grandfather chose to flee specifically in 1910. Speaking to Gechtman, I got some answers that helped elucidate my historical mystery. In 1909, she told me, Pereyaslav was engulfed in gang violence. One outfit, the Zelonyi, or Green Gang, named after a local warlord whose last name happened to be Green, robbed and murdered Jews in a series of pogroms.

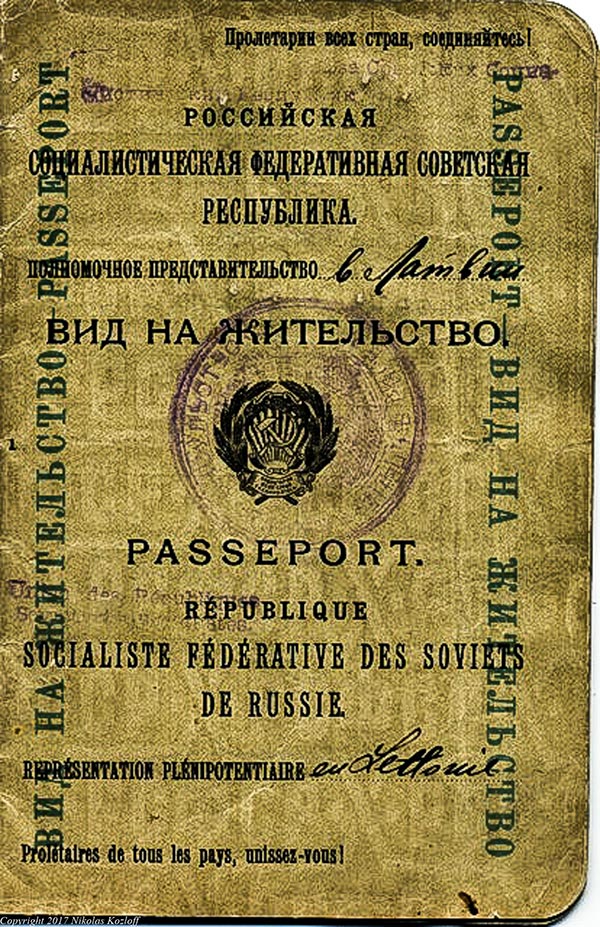

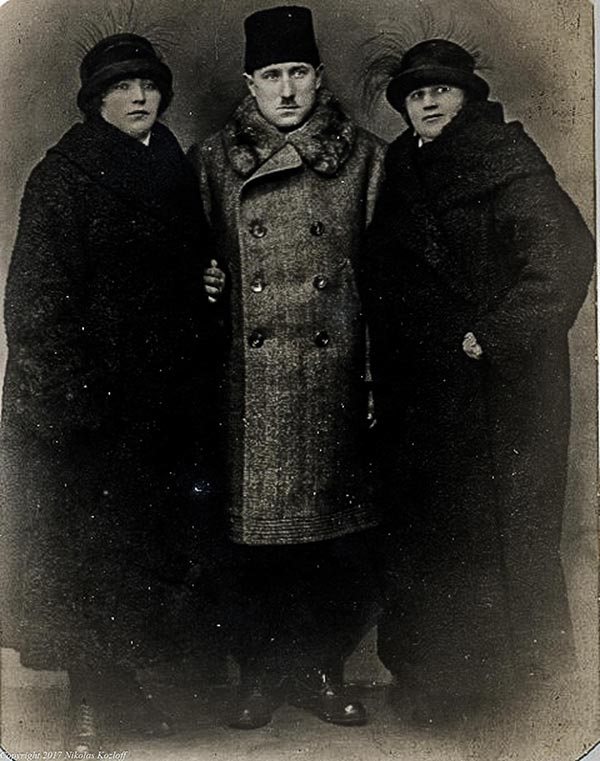

As it turns out, the Kozloffs were fortunate to get out of Ukraine when they did. After my family departed, the plight of Jews became exponentially worse. With the outbreak of World War I, Ukraine witnessed tremendous political turbulence. In 1917 the Czarist regime fell and was replaced first by a provisional government and later by the more radical Bolsheviks. Ukraine then declared independence, which sparked a brief war with the Soviets. If that were not enough, the Germans also occupied the country at the end of the war, and a costly civil war ensued, lasting from 1918 to 1920.

To this day, such turbulent history carries deep political meaning. Many Ukrainians look back on the civil war era nostalgically, seeing it as a period when they stood up to Moscow and the Soviets. The Ukrainian Diaspora, meanwhile, may extol nationalist struggle while demonizing the Soviets. (Take, for example, this recent historic exhibit at the Ukrainian Museum in New York dealing with contemporary Soviet propaganda and posters.) However, the question is whether Ukraine demonstrated multi-ethnic tolerance during this key but chaotic period of history.

Note to Ukraine: Be Careful With the Nostalgia

Initially, at least, local Jews seem to have looked upon burgeoning Ukrainian nationalism with a degree of approval. According to the Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, Jews and Ukrainians collaborated for “both pragmatic and idealistic reasons” and sought to bring about a kind of post-revolutionary democracy. To their credit, Ukrainians pledged to grant Jews local autonomy while extending the community’s individual and community rights and even promised to make Yiddish an official state language.

However, such “lofty ideals” were only shared by a “small circle of politically active Jews and Ukrainians in Kyiv and major cities.” As the Yivo Institute writes: “The dominant experience of Jews in Ukraine during the civil war period was one of violence, as hordes of pogromists swept across the countryside. Various military organizations and independent hooligans killed tens of thousands of Jews in the worst violence ever experienced in the region to that time.”

Ukrainian Nationalism and Lenin

To be sure, all different kinds of forces were hostile to Jews during the Ukrainian civil war, from the anti-Soviet White Army to the Red Army. However, in light of the historical record, it is perverse that some Ukrainians champion this brief chapter of history. Indeed, the Yivo Institute writes that Ukrainian troops perpetrated the largest proportion of pogroms. According to scholars, so-called “Cossacks” allied to the Ukrainian government were also involved in such pogroms. (For more on Cossacks and their present-day political relevance, see below.) Such developments are a little ironic, since the Ukrainian authorities had previously extended rights and privileges to the Jewish population. However, the government apparently was unable to control its own unruly troops and may have even turned a blind eye to abuses.

Today Ukraine is making a big push to eradicate its Soviet past, and recently the parliament in Kyiv even banned communist symbols and names. As part of the legislation, all monuments and place and street names associated with Lenin will be removed. But while no one is excusing the excesses of totalitarian rule, in certain respects Lenin has a better historical record than Ukraine during the civil war. In fact, though the Red Army was guilty of some anti-Semitic violence toward the end of World War I, many Jews eventually joined the Soviet army as a means of self-defense.

Perhaps Jews were favorably impressed with Lenin, a revolutionary who vehemently opposed anti-Semitism. According to the Yivo Institute: “Jews flocked to join the Red Army in such numbers that a special section had to be set up to train these Yiddish-speaking youngsters who were probably holding a weapon for the first time in their lives.” Suspecting that the Jews were becoming increasingly pro-Soviet, pogromists went on the rampage and attacked Jewish communities in a vicious cycle to the bottom.

Cossack Controversy

For Ukraine, a newly independent country, such debates carry deep political meaning, and while the country is more tolerant of ethnic minorities than many other nations are, Kyiv needs to make greater strides when it comes to understanding its history. To this day, many Ukrainians embrace a kind of kitschy nationalism as well as highly problematic historical symbols such as the mythical Cossack. While the mere mention of Cossacks is enough to instill fear in the hearts of Jews, many Ukrainians seem completely oblivious to such controversies and become defensive when confronted with such criticism.

Recently I became aware of this Ukrainian nationalist constituency while checking my inbox. Indeed, trolls routinely sent hostile and anonymous emails accusing me of being a paid stooge of the Kremlin and Vladimir Putin. Such a response is perplexing given the lengths I have taken to explain the subtle nuance and historical role of the Cossack. In a recent article, I pointed out that over time, Cossacks weren’t always anti-Semitic, let alone authoritarian. What is more, a lot of Cossack cruelty must be traced back to Russia and the age of the Czars.

Chmielnicki Massacre of 1648-1649

However, one must be careful not to twist history in accordance with present-day political agendas. While many Ukrainians would just as soon blame Russia for all their historical misfortunes, such claims don’t withstand serious scrutiny. Take, for example, the role of Cossacks in the Chmielnicki Massacre of 1648-1649. In the 17th century anti-Semitism flourished, and many lower-class Ukrainians, including Cossacks, accused the Jews of working on behalf of wealthy landowners. As they rose up against their Polish rulers, the Cossacks also turned against the Jews. During the Chmielnicki Massacre, Cossacks murdered Jews, and many communities were utterly destroyed. Cossack cruelty was so systematic that many Jews chose to flee and be sold into slavery by Crimean Tatars. Eyewitness accounts speak of Cossacks ordering Jews to dig their own graves and burying women and children alive.

Estimates differ as to the total number of Jewish casualties, but according to the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, as many as 125,000 were killed during massacres. After I published my original article, a predictable flood of Kyiv nationalists inundated my inbox with emails claiming that all Ukrainian Cossacks were freedom fighters. Somewhat more polite was Dr. Frank E. Sysyn, the director of the Peter Jacyk Centre for Ukrainian Historical Research at the University of Alberta. Rather than praise me for taking on Ukraine’s sacred cows, Sysyn charged that I overgeneralized and conflated the history of Ukrainian and Russian Cossacks.

While Sysyn admitted that the Chmielnicki Massacre was indeed bloody and left a lasting memory amongst Eastern European Jews, the scholar disputed high-end casualty estimates. Sysyn claimed that there may have been some 50,000 Jews living within the core areas of the revolt, and another 50,000 in western Ukraine, where losses were lower, so a figure of 125,000 would not have been possible. Some recent estimates in the scholarly literature contend that some 20,000 Jews may have perished. But whatever the case, the Chmielnicki Massacre is a harrowing and black chapter of history and cannot be so easily dismissed by Ukrainian nationalists.

Moving Toward a Pluralistic Society

Today Ukraine is a far cry from Serbia, with its own brand of aggressive nationalism. Moreover, Ukrainian history is replete with example of multi-ethnic tolerance and coexistence, and the experience of Pereyaslav, home to my forbears, bears this out. Yet far too often, segments of the Ukrainian population are simply tone-deaf when it comes to problematic episodes in the country’s history. If the new nation is ever to move forward, it must do a better job of coming to grips with its past. Perhaps the first step for Ukraine is simply to acknowledge the historical role of different minority groups.

During my recent research trip to Kyiv, I caught up with Denis Pilash, a left-wing political activist. Ukrainian history, he remarked, “is just based on the view of one ethnic group and nation building. It’s all about Ukrainians, hardly anything about Jews and Crimean Tartars, Poles and Armenians.” Later, in Kyiv’s old Jewish quarter of Podil, I spoke with Kyril Danilchenko of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress. Danilchenko, who isn’t Jewish himself, said that when he tells other Ukrainians he works for a Jewish organization, they express curiosity. “They don’t know much about Jewish culture,” he said.

It’s a similar story in Pereyaslav, where locals felt as if an important historical heritage had been neglected. At the Shalom Aleichem museum, I asked director Kucherenko whether she thought the larger-than-life Yiddish writer had received his just due. “We are trying to get some attention from the Ministry of Culture,” she said, “but Shalom must be raised higher, because the recognition is inadequate.” Historically, she added, the museum suffered from a policy of neglect, and the premises had even been closed for a time. Nevertheless, the Shalom Aleichem museum had recently become more popular, and Kucherenko hoped this would spur a Yiddish revival. “I myself am learning Yiddish at the moment,” she added enthusiastically.

Wonderful article which clarified my grandfather Julius Kozloff history. Iwould love to learn more and perhaps make contact with unknown relatives.

Jan Prystowsky

cleveronq@aol.com

You live in Detroit?