Darwin and Cultural Genocide in Argentina

From 1832-1835, Charles Darwin traveled across South America both on land and at sea aboard HMS Beagle, during which time he uncovered fossils which would later inform the theory of evolution. Though many are familiar with Darwin’s exploits, perhaps fewer are aware of shocking ethnic cleansing which formed the backdrop of his voyage. Indeed, even as Darwin reflected on the physical extinction of ancient megafauna, the scientist was also confronted with the extinction of indigenous peoples.

In contrast to Uruguay, where Darwin was either unaware or uncurious about the fate of native Charrúa people, Argentina was another matter. During his travels, Darwin witnessed a cruel and barbarous extermination campaign waged on the pampas, the likes of which shocked the young scientist. What is the cultural legacy of Darwin’s voyage in Argentina? I’ve come to Buenos Aires and Patagonia to discuss fraught history with historians and indigenous people.

Disembarking from the Beagle in August 1833, Darwin made his way to the encampment of Juan Manuel de Rosas, future dictator of the country. Rosas was engaged in the somewhat misnamed “War of the Desert,” which was prosecuted in a fertile region of the pampas. The area is naturally dry owing to low rainfall, but nevertheless capable of irrigation given that three rivers flow through the region, namely the Negro, Colorado and Salado. During Rosas’ brief yet savage campaign, Argentine forces advanced beyond the aforementioned Colorado, and as far as the Negro.

There had never been unified indigenous resistance to the Argentine state, but rather a complex set of changing alliances. Like Plains Indians of North America, indigenous peoples around the Negro and Salado had lived off hunting and were expert horse riders. The pampas were dominated by several groups including the Ranqueles, which had attacked Buenos Aires ten years prior to Darwin’s arrival, stealing thousands of heads of cattle. Pampas indigenous peoples near the capital, meanwhile, were regarded as fearsome, since they stole women, plundered ranches, and frustrated settlers intent on land expansion.

Rosas, who came from an established colonial landholding family, had long-time experience with indigenous peoples. The politician in fact employed indigenous peoples as peons on his landed estates, or estancias. Tehuelche indigenous peoples had killed Rosas’ military grandfather on the latter’s southern estate. What is more, the same tribe had held Rosas’ father, an infantry captain, as a prisoner for five months until authorities in Buenos Aires agreed to pay ransom.

Striking back in 1833, Rosas’ forces attacked Ranqueles, Mapuche, Tehuelche and Pampas peoples. Noemí Goldman, a historian at the University of Buenos Aires, told me “one can’t speak of indigenous peoples as a homogeneous group, but rather as different tribes” (a map dealing with Rosas’ military campaign illustrates the position of these tribes in geographical relation to Buenos Aires).

A consummate opportunist, Rosas divided indigenous groups into separate categories: friends, allies and enemies. Friends were permitted to settle within Buenos Aires province, and even on Rosas’ estancias, while allies could retain their territory and independence. Both groups were given cattle and other goods to secure their allegiance. Politically astute, Rosas even learned Puelche (also known as Gününa Küne or Pampa) and later compiled a Grammar and Dictionary of the Pampa Language.

The enemies list, by contrast, was comprised of Ranqueles and Mapuche which had plundered villages and pursued raids, known as malones. Goldman remarked that Rosas was a skilled negotiator: in exchange for rations and yerba maté, friendly tribes agreed to protect the border and were allowed to enter Buenos Aires. Rosas’ allies, therefore, could act as a buffer of sorts against hostile tribes engaged in everything from smuggling to raiding.

No doubt, Rosas wished to put an end to malones and rescue captives who had been held by indigenous tribes. On the other hand, the politician had other self-interested motives when it came to prosecuting the desert campaign. In late 1832, Rosas resigned as governor of Buenos Aires province and sought to retain a cadre of skilled soldiers from the capital, which allowed him to maintain his power base. By conquering indigenous lands, Rosas could distribute such territory to his cronies for cattle ranching, thereby enhancing his prestige.

Julio Djenderedjian, Goldman’s colleague and a fellow historian, said that up to 1810, the province of Buenos Aires was restricted in size, but over succeeding decades the authorities were gradually able to extend their territory. Crucially, Djenderedjian remarks, Rosas was able to exert control over the commercial hub of Tandil, frequented by indigenous peoples engaged in the poncho trade. To the south, meanwhile, Buenos Aires had established a fort at Bahia Blanca, a site where Darwin would make important fossil discoveries.

The scientist was appalled by senseless violence, remarking how the military killed indigenous peoples, with “the Indians doing the same by the Christians.” “It is melancholy to trace,” the scientist added, “how the Indians have given way before the Spanish invaders … Not only have whole tribes been exterminated, but the remaining Indians have become more barbarous: instead of living in large villages, and being employed in the arts of fishing, as well as of the chase, they now wander about the open plains, without home or fixed occupation.”

Even amid suffering, Darwin made astute observations concerning indigenous culture, describing everything from cooking to women’s adornments. At one point, the naturalist noted how a local Walleechu tree serving as a religious altar was surrounded by tokens, including cigars and cloth. Darwin also observed toldos — rudimentary tents supported by wood planks and covered in animal hides — which in turn comprised larger tent villages known as tolderías.

It’s unclear if Darwin was knowledgeable about individual tribes, though he does reference the Tehuelches, known as “people of the south” or Aónikenk, which had endured encroachment upon their lands. Tehuelche language had been eclipsed by Mapuche invasion, though the latter in turn adopted many Tehuelche customs, such as living in toldos. Though the Tehuelche had originally been seasonal hunter gatherers, land colonization and sheep farming disrupted the traditional indigenous economy.

Despite this brutal history, in April, 1833 Rosas managed to secure the support of Cachul, a Tehuelche chief, as well as Pampas chief Juan Catriel, both of whom assembled at Tandil. Traveling along the Negro River, Darwin noted Rosas’ forces had made the country “very tolerably safe from Indians.” The scientist added that Rosas deployed around six hundred Indian allies.

It does not seem the naturalist witnessed atrocities firsthand, though Darwin relates chilling anecdotes. In one attack he notes, “the Indians were about 112, women & children & men, in number. They were nearly all taken or killed, very few escaped. Only one Christian was wounded. The Indians are now so terrified that they offer no resistance in body; but each escapes as well as he can, neglecting even his wife & children.” Darwin conveys the scorched earth policy in gruesome detail, noting “the soldiers pursue & sabre every man…This is a dark picture; but how much more shocking is the unquestionable fact, that all the women who appear above 20 twenty years old, are massacred in cold blood.” Indigenous children, meanwhile, were either “saved, to be sold or given away as a kind of slave.”

Speaking with an “informer,” Darwin questioned the sheer brutality: “I ventured to hint, that this appeared rather inhuman. He answered me, ‘Why what can be done, they breed so.’” Rosas moved to corner retreating enemies south of the Negro River by paying Tehuelches to slaughter fellow indigenous peoples, “but if they fail in doing this, they themselves shall be exterminated.”

By early 1834, having quashed resistance while expanding the cattle ranching frontier, Rosas began to withdraw. The politician’s forces managed to liberate three thousand captives, most of whom were women. “A good many horses were recovered,” Darwin writes, “which had been stolen from B. Blanca. Amongst the captive girls, were two very pretty Spanish ones, who had been taken by the Indians very young & now could only speak the Indian language.” Though Rosas managed to stamp out malones, the conflict came at a terrible price, with anywhere between 3,000-10,000 indigenous casualties, not to mention tolderías destroyed by Buenos Aires forces.

Though Darwin decried cruelty inflicted on the native population, he himself participated in cultural desecration. Traveling far to the south in Port Desire, the scientist made his way up a hill and discovered an indigenous gravesite. “The Indians,” he remarked, “always bury their dead on the highest hill, or on some headland projecting into the sea. I imagine it is for this reason they come here; that they do pay occasional visits is evident, from the remains of several small fires & horses bones near them.”

The grave, which Darwin surmised must have been quite ancient, “consisted of a heap of large stones placed with some care… & at the foot of a ledge of rock about 6 feet high. In front of this & about 3 yards from it they had placed two immense fragments.” In one cringe-worthy passage, Darwin describes how he and a party of officers “accompanied me to ransack the Indian grave in hopes of finding some antiquarian remains.” The party “undermined the grave,” but there were no bones. Darwin observed other heaps of stones on neighboring hills, which had similarly “all been displaced; perhaps by sealers or other Voyagers.”

To be sure, the scientist was appalled at what he had witnessed on the Patagonian frontier, but the gravesite incident reflects callousness towards indigenous heritage, and perhaps even fatalism about cultural extinction. “In another half century,” Darwin remarks, “I do not think there will not be a wild Indian in the Pampas North of the Rio Negro.” A man of his era, Darwin viewed the advance of civilization as “a triumphant progress, morally justified and probably inevitable.” The naturalist believed in a hierarchy of races, not just in terms of social complexity and technological prowess, but also as far as mental capabilities were concerned.

In the following decades, indigenous peoples were pushed to the south, until they were ultimately defeated by Julio Roca’s Conquest of the Desert in the 1870s and 1880s. During the campaign, explorers and collectors took part in military operations, while naturalists placed indigenous skulls and skeletal remains in museum displays. Tehuelche, in fact, were kidnapped and exhibited against their will in France and Britain. After they were devastated by outside epidemics, deportations and matanzas (slaughters), remaining Tehuelche became culturally assimilated by European settlers. Today, their numbers have dwindled, which has led some to try and revive the Tehuelche language.

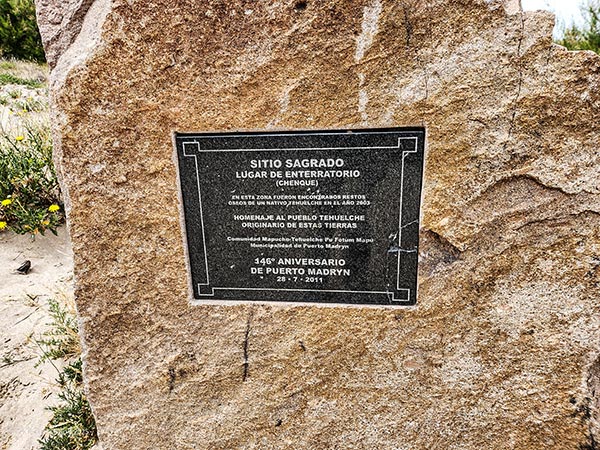

To get a better sense of indigenous legacy and heritage, I flew one hour south of Buenos Aires to Puerto Madryn, capital of Chubut province. The word Chubut comes from the Tehuelche word chupat, meaning transparent: an indigenous reference to the Chubut River. Originally established in 1865, Puerto Madryn saw peaceful co-existence between Welsh settlers and Tehuelche peoples. Climbing a hill, I came upon the Monument to the Tehuelche Indian and nearby Welsh Museum. Strolling across the highway, I observed a curious historic Welsh-indigenous burial ground.

I later traveled outside town along a dusty road. Arriving at a modest house, I spoke with Cándido Sayhueque, Municipal Director of Indigenous Affairs. Sayhueque, who shares both Mapuche and Tehuelche indigenous roots, said that significant archaeological finds had been made within the general vicinity of the Welsh-indigenous burial grounds. Five years ago, while out on a walk in the dunes near the beach, a couple came across a partially exposed skull. Unlike Darwin, the onlookers were careful not to disturb the grave. Snapping some cell phone photos, they immediately called in archaeologists and indigenous representatives like Sayhueque, who conducted a sacred ceremony including music and singing.

Researchers uncovered the bones of a squatting male who had been wrapped in guanaco hides. Scientists found seashells scattered amongst the bones, which led indigenous peoples to baptize the individual Puel Lafken Wentru, meaning “Man of the Eastern Sea” in the Mapuche language. Sayhueque told me remains were 2,800 years old, though curiously guanaco hides were more recent and dated to 1,500 years old, suggesting the man may have been unearthed, reburied and honored by fellow native peoples. In a nod to tradition, Sayhueque and others reburied the skeleton once more in the original spot after scientists had concluded their investigation. There is no gravesite or official sign, which could help to deter looters and tourists. “I prefer to leave it this way,” Sayhueque says, “though surely others will disagree” by arguing the site should be labeled more prominently.

The conversation verges on past and present, as Sayhueque reflects on the plight of his people. There had been rivalry between the Mapuche and Tehuelche over natural resources, he says, and Rosas exploited indigenous divisions. Despite this history, there has been intermixing over time, and today many trace their lineage back to indigenous roots. Indeed, Sayhueque estimates that out of Chubut’s overall population of 600,000, a full 150,000 carry indigenous surnames.

On the other hand, the right-wing Milei government recently conducted raids on Mapuche communities in Chubut, claiming indigenous peoples were responsible for causing wildfires. The Mapuche inhabit lands which are of great interest to investors seeking to extract raw resources once again. “Repugnant sectors of society have labeled indigenous peoples as terrorists,” Sayhueque remarks, including business and landowners. Though Darwin predicted the demise of Argentina’s indigenous peoples, the struggle for cultural survival continues.

Leave a comment