Ukraine: What’s the Role of Religion in Post-Maidan Milieu?

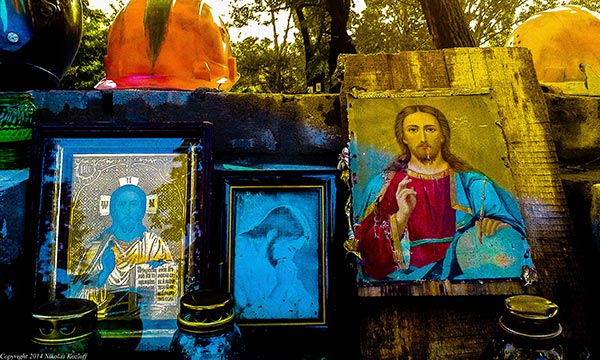

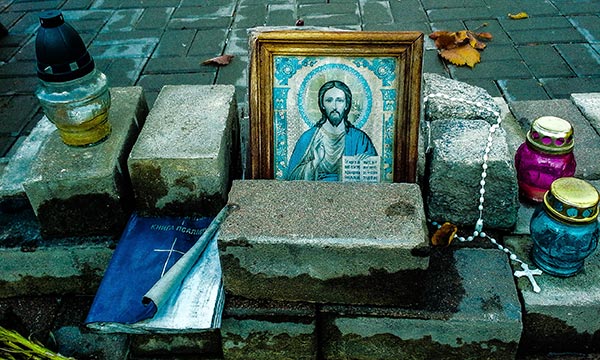

During a recent trip to Kiev, I was struck by mementos placed in and around Kiev’s Maidan square. The plaques featured individual photo portraits of fallen martyrs — the so-called “Heavenly Hundred” who had sacrificed their lives during violent protests against the unpopular government of Viktor Yanukovych. What particularly got my attention about these mementos was the overt display of religious iconography. Lying alongside the photos, Ukrainians had laid rosary beads, framed religious images of Christ and other memorabilia. Taken together, the photos and other donated items took on the look of a shrine.

While many have sought to interpret the overall political meaning of Maidan square, few have dwelled upon underlying religious connotations. To be sure, Ukraine isn’t as religious as Russia, but nevertheless the Church plays a significant role in society. No one church dominates in Ukraine, with various branches including the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (linked to the Patriarchate of Moscow), the Patriarchate of Kiev and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church all holding sway. Though the Orthodox Church is the largest faith, other groups include the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church and the Roman Catholic Church.

Backward Social Beliefs

Recently, I conducted a research trip to Ukraine and caught up with some local political activists who had their own unique take on religion. Denis Gorbach of the Autonomous Workers’ Union says that historically the larger Ukrainian Orthodox Church has displayed backward and retrograde ideas. “They have their own agenda,” he remarks, “which is socially conservative, racist against blacks and all non-Slavic peoples [though they wouldn’t have any big problems with Germans or British], anti-Semitic and homophobic.” Gorbach adds for good measure that the hardcore Orthodox Church views itself in opposition to “rotten western values and multiculturalism.”

For a more complete view, I headed over to Kiev’s old Jewish quarter of Podil. There, I spoke to Josef Zissels, General Council Chairman of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress. Zissels confirms that the Ukrainian Church of the Moscow Patriarchate is “the most anti-Semitic amongst the churches.” Zissels says he’s actually been aware of this reality for a full 20 years, and anti-Semitic literature was even sold at such churches [Zissels adds however that he sees little evidence of such virulent anti-Semitism at other Orthodox branches of the church].

Celebrating Orthodox Kievan Rus

Larissa Babij works as an arts curator in Kiev. An American of Ukrainian descent, she moved to Kiev in 2005. Babij never really saw herself as a political activist, but when she observed that Ukrainians had little sway over their own cultural institutions she helped to found a group called Art Workers’ Self Defense Initiative. Since the breakup of the old Soviet Union, Babij declares, there’s been a kind of ideological vacuum in Ukraine and a counter-reaction to earlier forced atheism under Communism. In the absence of a strong state infrastructure within newly independent Ukraine, people don’t even know whether they’ll receive hot water tomorrow. As a result, some have turned to religion as a source of solace.

During the Yanukovych era, Babij says there was a rather corrupt church-state relationship at the very public and visible level. In July, 2013 Kiev’s Mystetskyi Arsenal art museum put on a show titled “The Great and the Grand.” The exhibit was designed to celebrate the 1025th anniversary of the baptism of Kievan Rus, which is the original medieval state considered to be the Orthodox foundation of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. In a very symbolic sense, then, the show was designed to foster closer cultural ties between Ukraine and Russia, and indeed Putin himself was invited to the show. What is more, Yanukovych exercised great influence over Arsenal, a museum which lacked its own political autonomy, even though the institution is state-funded and receives taxpayer money.

Museum Controversy

As if the political dimensions weren’t questionable enough, further questions soon arose about the relationship between church and state. When it became clear that the show was to be partially funded by top-ranking clergy belonging to none other than the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Babij grew concerned. Could the president be seeking to perpetuate his own state ideology favoring closer ties to the Church? As suspicions grew, a controversy erupted at the museum which eroded Arsenal’s already fast deteriorating reputation. On the night prior to Yanukovych’s personal visit to the museum, Arsenal’s director literally took a can of black paint and doused one of the exhibit’s artworks which she deemed immoral.

The work in question, a mural depicting a flaming nuclear reactor with priests and judges partially immersed in a vat of red liquid, soon became a cause célèbre as Kiev’s arts community rushed to the defense of creative self-expression. Prior to the opening, eight activists were arrested outside the museum protesting the creeping consolidation of church and state. In defending her controversial decision, Arsenal’s director claimed that the exhibit “should inspire pride in the state.” She added, “If you participate in [an] exhibition dedicated to the 1025th anniversary of the baptism of Kievan Rus, you don’t have to do your best to offend the faithful, to lower the reputation of all clergy.” In the wake of the controversy, Arsenal’s deputy director resigned in protest, while some suggested the director had come under pressure to eliminate controversial work in advance of Yanukovych’s visit.

Befuddled Church

Though certainly ominous, the Arsenal controversy did not lead to a consolidation of church and state in Ukraine though perhaps, if he had not been toppled from power, Yanukovych would have sought greater ties along these lines. But as Ukraine veered into Maidan political turbulence, the fractured church with its many denominations was forced to take sides. Historically, the Orthodox faith has placed greater emphasis on backing up state power, rather than supporting the aspirations of civil society. But with pro-Moscow Yanukovych clinging to power, top clergy was placed in an uncomfortable position.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church, with its ties to the Moscow Patriarchate and upper echelons of Russian political and ecclesiastical leadership, was placed in a particularly difficult situation. Initially, Maidan was sparked by pro-European elements unhappy with Kiev’s tilt toward the Kremlin. As events unfolded, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church sought to remain neutral in the midst of political crisis. Maintaining such neutrality proved difficult, however, since many members of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church were themselves pro-Western. Though the church was eventually obliged to back Maidan protesters and the subsequent government of Petro Poroshenko, it did so somewhat reluctantly and belatedly.

Other denominations got out in front of Maidan protests much earlier, however. Take, for example, the Greek Catholic Church. According to Zissels of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress, Greek Catholics were the most influential religious grouping represented on the Maidan. Furthermore, Zissels reports, his own organization enjoyed a “very good and strong relationship” with the Greek Catholic Church. However, Maidan served to unite diverse religious constituencies, ranging from Orthodox to Catholics to even Jews and Muslims.

Religion at the Maidan

Gradually, religious leaders began to assume more importance on the Maidan. When riot police attacked protesters, scattering a whopping 10,000 people, many sought refuge in the nearby historic St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery. There, demonstrators were protected by local monks belonging to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s Patriarchate of Kiev. Several days later, when riot police attacked again, a graduate student at a nearby theology school began to ring sacred bells next to a local cathedral. The noise and commotion could be heard for miles. In response to the call, priests dressed in cassocks and holding crosses stood between riot police and protesters as a gesture of peace. Later, the police withdrew without resorting to further violence.

Meanwhile, priests led daily prayers at the barricades. In the middle of the square, a chapel belonging to the Greek Catholic Church provided daily Mass, confession and even counseling. At night, priests from all faiths led a prayer after crowds recited the national anthem. Such developments began to raise eyebrows among Ukrainian progressives, however. At a certain point, Babij tells me, prayers were literally getting recited on the hour at Maidan. “It was definitely uncomfortable for those of us who are not really religious in that way,” she says. All of a sudden, she adds, religion became very dominant and “Maidan took on a homogeneity which might have been representative of the majority, or maybe representative of what some people thought the majority should be. But it definitely was not all-inclusive. It definitely had those patriotic, religious and nationalistic overtones.”

Religion in Post-Maidan Era

Despite such pronounced religious nationalism at Maidan, some believe there is little danger that Ukraine will somehow merge church and state. Though there was a rather corrupt church-state dynamic at play under Yanukovych, Babij thinks this trend is no longer as pronounced or significant. For now then, Ukraine seemingly hasn’t embraced the backward Russian model, where conservative religion has taken center political stage as of late.

Cyril Danilchenko, who works as Zissels’ personal assistant at the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress, believes the Orthodox faith doesn’t inform Ukrainian nationalism to the same degree as Russian nationalism. “In Ukraine,” he tells me, “faith is more of a personal affair. You don’t hear slogans like ‘we are Ukraine, we are Orthodox!'” Danilchenko adds that many Ukrainians simply see themselves as European and prefer a strong separation between church and state. In Russia by contrast, “it doesn’t work that way. The country has a state religion which is almost akin to Saudi Arabia.”

Hopefully, Ukraine will maintain a critical separation between politics and religion in the wake of Maidan. “Ukraine is definitely more secular than Russia,” Babij notes. After observing political controversies at the Arsenal museum, however, the curator isn’t under any great illusions. In the long-term, she adds, Ukraine still “has all the potential to go in the direction of Russia from a religious standpoint.”

Photos of Kiev’s churches http://kiev-foto.info/ru/tserkvi