Venezuela End Game: Dissecting Different Interest Groups and Agendas Within the MAGA Coalition

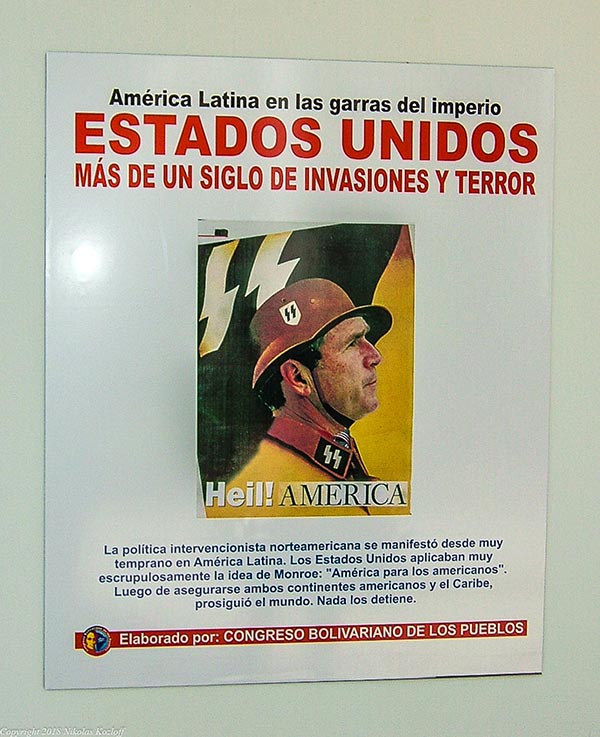

Now that the U.S. has captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, perhaps it is worth asking: what are the different interest groups within Trump’s White House and how are such factions likely to shape the trajectory of Venezuela’s political future? While U.S. foreign policy may be somewhat torn between conflicting agendas, Secretary of State Marco Rubio has prevailed with a muscular approach emphasizing regime change, or perhaps what could be considered “leadership change.” Some have argued that Rubio’s ties to right-wing elements in South Florida are most consequential when it comes to informing the diplomat’s priorities. The son of Cuban immigrants, Rubio grew up in Miami and is well known within the Venezuelan and Cuban exile communities, which called for Maduro’s ouster.

While serving as a Republican Senator from Florida, Rubio often criticized Maduro’s “Cuban-style dictatorship” while praising the Venezuelan opposition. During Trump’s first term, Rubio exerted influence over U.S. policy toward Latin America, and pressed the White House to recognize Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as president. Though the effort fizzled and Guaidó was obliged to leave Venezuela, Rubio was seen as a proponent of “maximum” pressure against the leadership in Caracas; that is to say, the strategy of imposing tough sanctions while charging Maduro and his circle with narcoterrorism.

If anything, Rubio’s star has only risen in Trump’s second term: in addition to his portfolio as Secretary of State, the Republican also serves as national security adviser. Earlier this year, it looked like Trump special envoy Richard Grenell might ease pressure on Venezuela in exchange for economic concessions from Maduro. Rubio apparently scuttled such efforts, as evidenced by U.S. missile strikes in the Caribbean targeting boats alleged to be carrying drugs. Reportedly, the deal championed by Grennell didn’t “meet the mark” for Rubio, who persuaded Trump to pursue a more radical approach, even as the Secretary of State pushed for CIA covert actions and extrajudicial killings.

Now that Trump has deposed Maduro, it’s unclear whether the president even believed his own ‘America First’ rhetoric predicated on supposed wariness of regime change. If reporting can be believed, however, the Secretary of State felt compelled to convince Trump to go along with his own plans by “re-framing” the Venezuela issue. Rubio won the day by switching from an emphasis on regime change to focusing on drug trafficking. Hoping to dissuade Trump from siding with his Secretary of State, Maduro addressed the U.S. president directly, remarking “you have to be careful because Marco Rubio wants your hands stained with blood, with South American blood, Caribbean blood, Venezuelan blood.”

Though Rubio’s backing of the Venezuelan opposition during Trump’s first term proved unsuccessful, neither Cuban American nor Venezuelan American voters punished the president or the former Republican Florida Senator in a political sense. This time, however, the stakes are much higher: now that Maduro has been ousted, Rubio could reap the political benefits, but if Venezuela descends into chaos, the Secretary of State could be tarnished, particularly if he decides to launch a presidential bid in 2028. It appears Rubio was willing to take that risk, however, since he believed that by toppling the Maduro regime, which has strong diplomatic ties to Cuba, the U.S. might in turn weaken Havana.

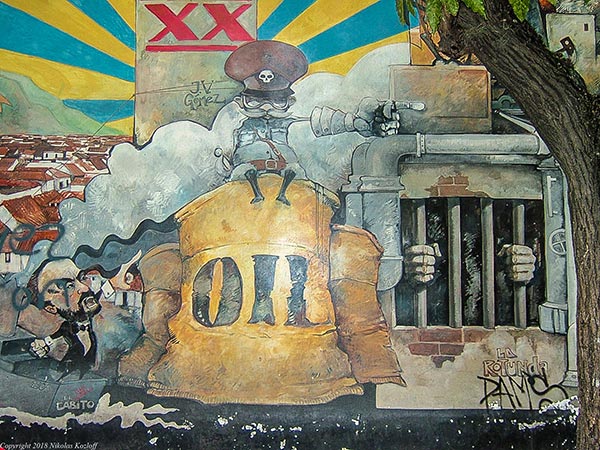

Where does oil figure in this high-stakes gambit? To be sure, Trump’s campaign slogan was “drill, baby, drill,” and the president has advocated expanding oil production. Moreover, Trump stated the U.S. should regain control over the Venezuelan oil industry. The president even argued the U.S. should retain Venezuelan oil from seized tankers, seemingly as part of a broader push towards “resource imperialism.” Though certainly motivated by geopolitics and Venezuela’s natural resources, Trump may seek to simply declare victory while satisfying his ‘America First’ base, thereby avoiding long-term nation-building. Some even doubt whether oil was truly at the center of Trump’s ambitions. Though “the concept of a war for oil is more emotionally satisfying and probably a side benefit” of any incursion, others argue that “the largest proven oil reserves in the world are more the spoils of war than its cause.”

Whatever the case, Trump’s team has certainly held long-time associations with the oil industry. As far back as 2010, when he first ran for Senate, Rubio was backed by Chevron and ExxonMobil while receiving more money from Koch Industries than any other candidate for Senate that year. Needless to say, the Koch brothers had invested heavily in oil and gas and led efforts to deny the reality of climate change. Parroting oil industry talking points, Rubio stated that climate change was not caused by humans.

In his second term as a Senator, the Floridian reversed himself and belatedly admitted this was not the case. However, even when he ran for president, Rubio avoided the challenges posed by climate change, favored rolling back environmental efforts of the Obama administration, and paid little attention to clean energy. Perhaps that is not too surprising, given that Rubio was backed by one of the biggest frackers in the U.S., who acted as the presidential hopeful’s adviser, thus “dispensing with the pretense of independence and turning his energy policy into a straight quid pro quo arrangement with fossil fuel interests.” In more recent years, Rubio has sought to shift the discussion away from curbing fossil fuels while emphasizing how we should adapt to climate change.

Just recently, in a move which may rise eyebrows, a federal judge approved the sale of oil refiner Citgo — a U.S.-based subsidiary of Venezuelan state-owned oil company PdVSA — to an investment company whose founder shared long-held financial ties to Rubio. Earlier, during Trump’s first term, the U.S. Treasury Department had sought to prevent Maduro from accessing Citgo revenue by authorizing a board selected by Juan Guaidó.

Despite his historic associations with the oil industry, Rubio pursued a slightly different approach toward Venezuela. During negotiations with Maduro, Trump envoy Grennell had persuaded the Venezuelan leader to open the oil sector in exchange for simply not being ousted. Maduro bent over backwards, offering the U.S. a dominant stake in his nation’s oil resources. In another last-ditch effort to head off intervention, Maduro sought to mend ties with ConocoPhillips, a company which had departed Venezuela in 2007 after the government seized its assets. Even as the Venezuelan agreed to concede preferential contracts to American companies, Maduro pledged to reverse oil exports from China to the U.S. He also stopped exporting oil to Cuba, which worsened electricity shortages on the island.

Even with such generous terms, however, Rubio doggedly engaged in a “power struggle” with Grenell. In the end, the Secretary of State succeeded in “sidelining” Trump’s envoy, who had pursued a more pragmatic approach. Rubio’s brazen tactics reportedly irritated oil interests intent on tapping Venezuelan reserves. It would seem then that oil companies, at least in this instance, were not on the same page as the Secretary of State, since regime change might lead to destabilization and a more uncertain business climate. Now that Maduro has been apprehended, it’s far from clear what will happen politically: the Venezuelan opposition isn’t very united, and though María Corina Machado has stated she is ready to govern the Andean nation, there are other exiles, as well as figures within the Maduro administration itself, who would also be interested in playing such a role.

In an effort to shore up support, the opposition has appealed to the oil industry by drafting a plan designed to privatize Venezuela’s oil reserves and open the latter to business. In New York, Machado buttered up corporate America, stating “our message to the oil companies is: we want you here…not producing crumbs of a couple hundred thousand barrels a day. We want you here producing millions of barrels a day.” Venezuela, however, is plagued by guerrillas and paramilitary groups which have enriched themselves though illicit activities ranging from gold smuggling to drug smuggling. It goes without saying that such groups may not willingly give up their arms.

Though the oil companies may not see eye to eye with the opposition when it comes to all the particulars, petroleum interests have long sought to get back into Venezuela. To understand why, we should go back to the late twentieth century. As I pointed out in my book, Hugo Chávez: Oil, Politics and the Challenge to the U.S., successive regimes in Venezuela managed to carry out important work in health and education during this period, and some oil wealth filtered down to the neediest. However, Venezuela still suffered from persistent poverty and unequal distribution of wealth.

Nationalization of the oil industry in 1975-76 was designed to change all that, and indeed the government wound up exacting a greater share of revenue from oil exports. This was reversed, however, under the subsequent policy of apertura (or opening of the oil sector) during the 1990s, when government revenue from the oil industry declined. Changing course once again, Chávez in 2005 mandated joint operation agreements with the oil companies, in which PdVSA would hold a majority share. Two years later, Chávez nationalized the last privately run oil fields in Venezuela.

Needless to say, U.S.-Venezuelan relations took a nosedive, and Caracas has been under U.S. energy sanctions since 2019. As a result, crude oil exports to the U.S. have dwindled. As a result, crude oil exports to the U.S. have dwindled. If you have deep pockets, however, you can persuade Washington to make exceptions. Take Chevron, which spent almost $7 million to lobby the U.S. government. Apparently, the effort paid off: under a special license, Trump’s Treasury Department allowed the company to export seventeen percent of Venezuela’s output back to the U.S., thus overturning a previous ban which had been imposed months earlier. But in granting the waiver, Trump exposed political fissures, since the Venezuelan opposition argues that any oil production with current leadership should be prohibited.

If the Maduro government collapses, Chevron would, in theory, be well placed to help repair Venezuela’s weakened oil industry. For years, the petroleum sector has been battered by sanctions, which has caused investment to dry up and led to difficulties in obtaining necessary equipment and spare parts. In addition, PdVSA has been mismanaged with an exodus of experienced oil personnel fleeing the country. Republicans believe Venezuela could turn into a windfall for oil companies, which might help to repair infrastructure including pipelines and rigs. In addition, U.S. refineries on the Gulf Coast are eager to receive extra heavy Venezuelan crude, which is usually less costly and as a result more lucrative to process.

Now that Maduro has been removed, Trump has brazenly claimed U.S. oil companies will head back into Venezuela which in turn could lead to a bonanza. But even if political conditions are suitable to resume operations, many technical questions remain. While improved management and investment could help boost oil production, such efforts would require a massive infusion of cash and recovery of the industry might take some time. Some observers believe it would take billions to restore the Venezuelan oil industry to its former status, thus raising the question of whether investment is truly worthwhile.

A further irony is that oil stands to lose its relative importance as an energy source in relation to renewables. Indeed, experts believe the oil sector isn’t growing like before and will start to decline in the late 2030s. Seen in this light, Trump’s Venezuela gambit is not only foolhardy on many levels but also risks consigning future generations to increased emissions at precisely the moment when the world should be moving toward decarbonization. In his risky pursuit of regime change, it would seem this was hardly a consideration for Rubio, who has been focused on his right-wing base and a potential presidential run in 2028, while only belatedly admitting to the underlying causes of climate breakdown.

Leave a comment