Darwin’s Fox and South America’s Unique “Canid Evolutionary Laboratory”

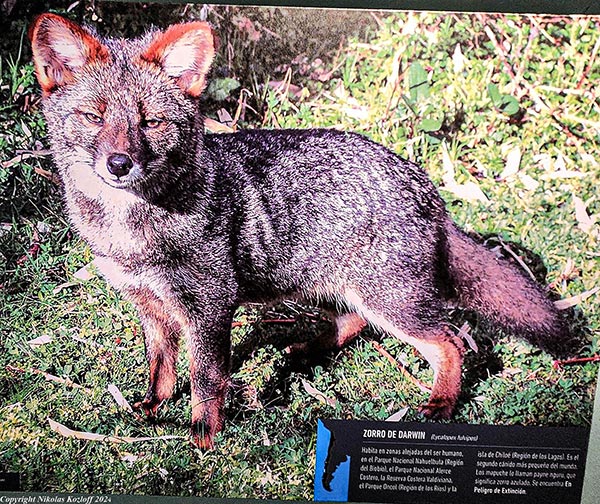

Though Charles Darwin is known for his study of finches inhabiting the Galápagos Islands, a discovery which later informed his theory of evolution, the scientist failed to scrutinize the backstory of other key wildlife during his voyage aboard HMS Beagle. While traveling in Chile in 1834, the young naturalist encountered an intriguing small and dark fox-like creature on San Pedro Island, located within the Chiloé archipelago off the coast. Darwin had heard there were foxes on Chiloé which seemed to be distinct from others on the mainland, but this was the first one he’d observed.

Unfortunately for the animal, Darwin was able to sneak up behind it. Naïve and unsuspecting, the creature gazed out with curiosity at the Beagle, anchored just offshore. “He was so intently absorbed in watching the work of the officers,” the naturalist wrote, “that I was able, by quietly walking up behind, to knock him on the head with my geological hammer.” Later, the scientist shipped the deceased creature back to England and the find made its way to the Zoological Society of London. Though Darwin mistakenly classified his creature as a subspecies of Chilla fox, we now refer to the animal as Lycalopex fulvipes, Zorro Chilote in Spanish, or simply Darwin’s fox.

If only Darwin had paid as much attention to his fox as he did to wildlife on the Galápagos, he would have uncovered a fascinating story of “adaptive radiation;” that is to say, the process by which creatures diversify from an ancestor into a variety of new animals. Like South America’s five other species of fox — which are technically not true foxes but rather “fox-like” canids more closely related to wolves and jackals — Darwin’s fox descends from a North American ancestor which lived from 3.9 to 3.5 million years ago. At the time, the Isthmus of Panama hadn’t fully formed, but ingeniously, canid ancestors made their way through a narrow strip of savannah called the Panama corridor.

Once they arrived in South America, canids spread into diverse ecological niches and became genetically distinct. The changes occurred quite rapidly, on the order of just one to two million years, which in evolutionary terms is the mere blink of an eye. Canids thrived, owing to their success within empty niches and absence of competition. Though such canids weren’t true foxes, some of them came to resemble the latter physically through the process of convergent evolution. As they evolved, South American foxes developed their own unique adaptations to specific habitats, thus reinforcing Darwin’s musing about “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.”

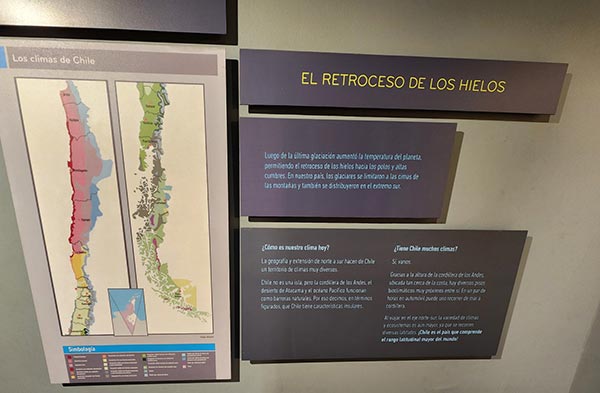

Retracing Darwin’s route in Chile last year, I wanted to learn about South America’s canid evolutionary legacy in light of current day environmental threats. South America served as an important evolutionary “laboratory” for canid natural selection. But how did Darwin’s fox in particular wind up on the island of Chiloé? In nearby Puerto Montt, I sat down with Carlos Leiva, president of environmental NGO Andean Alerce. During the Ice Age, he remarked, Chiloé was connected to the mainland by a land bridge. Some 15,000 years ago, however, the land bridge was severed amidst sea level rise, and this gave rise to two isolated populations of Darwin’s fox on Chiloé and the mainland, which today consume different diets. Scientists believe the current distribution of Darwin’s fox on the mainland may represent a “relic” spread out over a formerly wide geographic range, before Chiloé split from the mainland in the late Pleistocene.

Unfortunately, Darwin’s fox is now endangered, and is considered the canid species most at risk of extinction in the world, with a population of less than one thousand mature individuals split between Chiloé and the mainland. Though Darwin failed to grasp the story of South America’s unique canid evolutionary laboratory, protecting the likes of Darwin’s fox is of the utmost importance given the continent currently displays the world’s greatest canid diversity.

That’s a tall order, however, given modern-day challenges. A solitary creature, Darwin’s fox inhabits temperate forests on Chiloé and the mainland, and is threatened by climate change. The animal moreover faces habitat loss due to expansion of timber plantations, unsustainable logging and threat of displacement from forest fires. Perhaps, the fox dislikes such plantations, given that researchers haven’t found any evidence of the animal’s presence within these enclaves. Domestic dogs, meanwhile, have attacked and killed Darwin’s fox, while exposing the latter to canine distemper virus (CDV).

With their habitat declining due to both human activity and global warming, Darwin’s fox has become increasingly isolated, which in turn decreases the creature’s ability to find mates and ensure genetic diversity. Given these underlying trends, it’s not surprising that even local residents have scant experience with the animal. From the coastal city of Puerto Montt, I took a bus and ferry to Chiloé. During the trip, I asked my guide if she’d ever seen Darwin’s fox. “No,” she answered, “only in books, drawings and videos.” To have any chance of glimpsing the animal up close, she said, one would need to travel deep within Chiloé’s native forest.

A land bridge once enabled Darwin’s fox to make its way to Chiloé, but in an ironic twist of fate, modern construction may pose an environmental risk to the animal as well as other local wildlife. The Chacao Channel Bridge, also known as Chiloé Bicentennial Bridge, will link the island to the mainland. Work began in 2017, and the bridge is expected to open in 2028. When completed, the construction will be the longest suspension bridge in Latin America and reduce journey time in comparison to the ferry. On the other hand, Chiloé will have to invest in further road construction due to the anticipated increase in traffic. Opponents, including Huilliche indigenous peoples, claim the bridge is simply aimed at crass resource extraction: in the long term, they say, the project may be harmful and even dangerous, since it could lead to an increase in logging and pollution.

Back on the mainland, I’m hoping for another opportunity to glimpse Darwin’s fox. Traveling to nearby Vicente Pérez Rosales National Park and Petrohué Falls, I marveled at lush temperate rain forest. From the park, I also traveled to the base of Osorno volcano. In 1835, the volcano erupted and startled a young Darwin who observed the event from Chiloé. Though the scientist himself was unaware, the range of Darwin’s fox encompasses a wider area than just Chiloé. Indeed, the creature inhabits several forested areas on the mainland, including Nahuelbuta National Park, some three hundred miles north of Puerto Montt. However, the creature has also been spotted in the Valdivian Coastal Range, just north of Osorno.

At one point, while hiking along a path in the forest, I spotted a captivating fox which darted before me and disappeared before I could snap a photo. My guide, however, remarked that it was not Darwin’s fox, but rather another canid known as Zorro Chilla. Today, populations of mainland Darwin’s fox live in the same geographic area as canids like Chilla (also known as South American gray fox), and possibly Culpeo (or Andean fox). My guide added that climate change has impacted local wildlife, and foxes wander around looking for food until people throw them scraps. In light of these concerning conditions, captive breeding programs and habitat restoration will be utterly essential in any future conservation efforts. Scientists have grown concerned too that inbreeding may have contributed to a decline in genetic diversity, which particularly afflicts mainland populations of Darwin’s fox.

Modern science, however, may hold an answer to these challenges. Researchers are mapping the fox’s genetic blueprint, which can reveal disease vulnerabilities and levels of inbreeding. Gene sequencing, meanwhile, could enhance the fox’s long-term resilience, and even provide an “evolutionary template” for species recovery. In time, scientists hope to identify the most endangered fox populations and animals exhibiting low genetic variation, while subsequently designing thoughtful breeding programs. Such gene sequencing has literally made the case for greater conservation efforts, since research suggests Darwin’s fox is descended from canid populations which once enjoyed a wider geographic distribution. Needless to say, destruction of forest habitat has greatly impeded this historic range.

Some time later, I’m in Santiago and feeling regretful about not getting to see a real Darwin’s fox. I consoled myself by heading to the city’s National Museum of Natural History. Roaming around, I spot exhibits dealing with Chile during the Ice Age and after. The museum also featured a display about Nahuelbuta and contained a photo of Darwin’s fox. Pondering the intriguing twists and turns of canid evolution in South America, I sat down with Bárbara Saavedra, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society in Chile. When I asked if she had ever seen a Darwin’s fox, she said the animal had eluded her, though she did observe droppings which were probably signs of the creature.

“Chile isn’t distinguished so much by the number of species it has, but rather its own iconic animals such as Darwin’s fox,” she explained. “The creature is an ancient relic going all the way back to the Ice Age,” she adds, marveling at how the animal not only managed to withstand climate change but also adapted to drastic fluctuations and conditions over the millennia. Darwin’s fox must be considered a great survivor, Saavedra remarked, and it has now fallen upon us to honor South America’s unique canid evolutionary laboratory by creating conservation refuges aimed at repopulating the species in the face of turbo-charged global warming.

Leave a comment