The Plight — And Blight — of Darwin’s Humble Potato

If we are to successfully feed the planet, we must protect the humble potato. Indeed, the tuber is the third most important world-wide food crop after rice and wheat, and, what is more, potato is considered one of the most critical staples in terms of food security, particularly in developing countries. Despite this, climate change and high temperatures are expected to threaten yields, which makes it utterly imperative to maintain potato biodiversity. There is perhaps no more important place to preserve such biodiversity than Chiloé, an archipelago off the coast of Chile. Indeed, more than a whopping ninety percent of world-wide potato varieties can be traced to Chiloé.

Such remarkable variety was noted by none other than Charles Darwin, who traveled to Chilóe in 1835 during his voyage aboard HMS Beagle. The young naturalist noted that wild potatoes were abundant here, though “watery and insipid.” The scientist later shipped several types of potato back to England in order to grasp the biological concept of species and delve into how pathogens result in blights. So fascinated with the potato did Darwin become that he invested four decades studying the tuber. In an echo of ongoing problems which still reverberate today, Darwin became interested in food security during the Irish famine. In fact, the scientist was involved in the first research to come up with resistance to blight and even financed a breeding program himself in Ireland.

Last year during summer I traveled to Chiloé to explore Darwin’s legacy in light of climate change. Indigenous peoples cultivated up to one thousand varieties of potato here prior to the arrival of agricultural mechanization. Though native potatoes are rich in antioxidants and vitamins, farmers were subsequently told to cultivate international varieties which could attract higher demand. Now, however, there’s an effort to revive native potatoes and market them to cities and high-end restaurants, while potato cooperatives have targeted niche markets. Nelly Carrasco, my tour guide in Chiloé, said that marketing native potatoes could be sustainable, but not everyone was accustomed to purchasing traditional varieties.

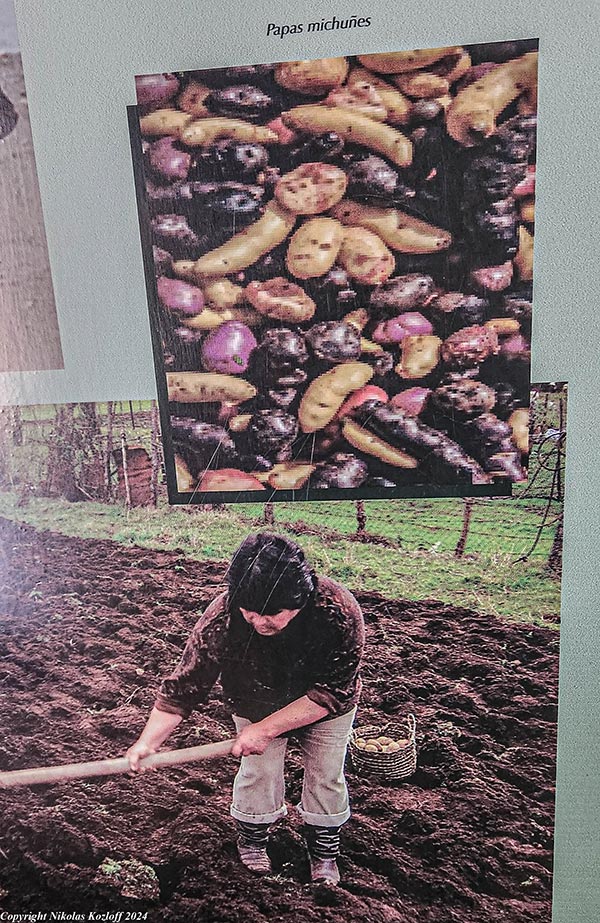

Pamela Urtubia, an anthropologist and Director of the Historical Museum of Puerto Montt, located near Chiloé, told me potatoes are a key staple of the local diet. Indeed, potatoes are the main crop cultivated in Chiloé, and islanders take pride in ancestral potatoes, which come in a variety of colors ranging from purple, blue, violet and yellow and display uniquely elongated and curved shapes. Importantly, some varieties of Chiloé potato can withstand high temperatures and require less water without reducing yields, which could prove vital when it comes to coping with global warming and maintaining a healthy food supply. Some varieties, moreover, are resistant to blight and can adapt to poor-quality soil.

Even for resilient Chiloé potatoes, however, there may be limits. There is concern amongst researchers that climate change could negatively affect temperate areas of southern Chile such as Chiloé. Though weather conditions are optimal for potato cultivation here, including high rainfall, future temperature increases could adversely impact potato farming, particularly during summer heatwaves. Indeed, during my own tour of Chiloé, which included a typical Chiloé lunch accompanied by purple potatoes, temperatures were scorching.

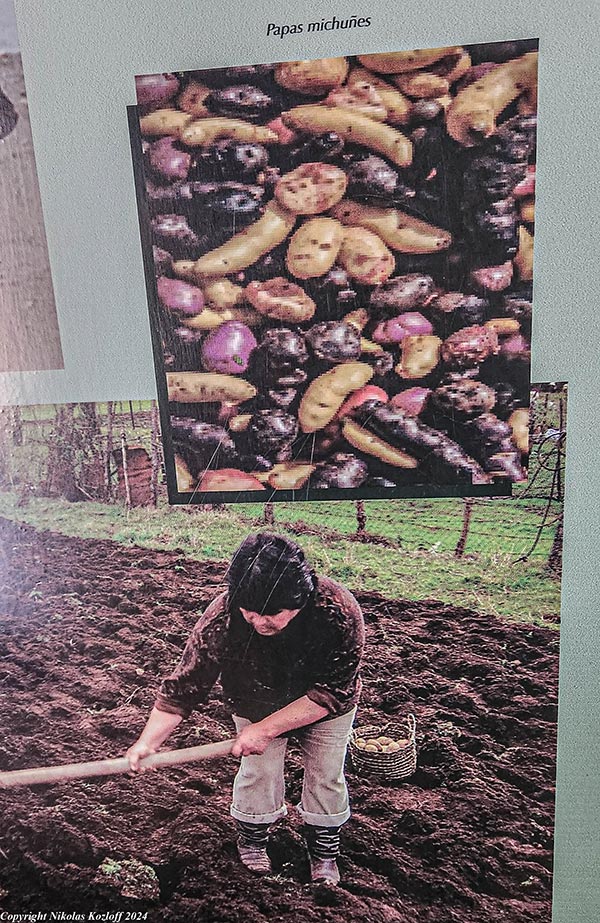

In 2022, Carrasco remarked, there was a water shortage which was detrimental to agriculture. To safeguard ancestral knowledge, Huilliche indigenous peoples and researchers have set up seed banks, and rural women are key in preserving genetic diversity and conservation. Valentina Vergara, a sociologist working with local Puerto Montt NGO Andean Alerce, said women “are the ones in charge of saving seeds for coming years, and they are often proud of owning the same seeds their great-grandmothers cultivated.” Scientists, meanwhile, hope to take advantage of such ancient knowledge by identifying Chiloé native potatoes and later crossbreeding specific varieties in order to build up traits adaptable to climate change.

Though Darwin recognized that Chiloé potatoes were “indigenous” to the region, and were cultivated by “wild and Chilotan Indians,” he failed to grasp the full extent, let alone importance, of native peoples’ contributions. Despite debate over where potato domestication first took place, whether Peru or Chile, researchers have uncovered traces of wild potato at the Monte Verde archaeological site located near Chiloé, dating back to almost 13,000 B.C.

To give a sense of how ancient the potato truly is, consider that scientists have uncovered human remains at Monte Verde, but also animal bones belonging to mastodons. Indeed, the Monte Verde discovery caused a stir within the scientific community, since dating of early human presence in the Americas had to be pushed back. Not surprisingly, then, Chilote cuisine, which has its origins in pre-Hispanic traditions originating from native Chonos and Huilliche people, relies extensively on potato. One dish, curanto, incorporates seafood, meat and potatoes wrapped in leaves and cooked in an underground hole lined with hot stones.

While Darwin disparaged Chiloé potatoes as “insipid and watery” during his voyage of discovery, these ancient tubers may hold the key to protecting food security in a rapidly warming world.

Leave a comment