Darwin and Mystery of the Fuegian Dog

What constitutes an “invasive species” and should animals associated with indigenous peoples be considered “native wildlife”? Last year, while retracing Charles Darwin’s voyage in Chile, I pondered such questions. During one of the more memorable episodes of my trip, I found myself in Punta Arenas, the most southerly city in the world. Walking around the Salesian Maggiorino Borgatello Museum, I took in ethnographic exhibits dealing with Yagán and Selk’nam indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego, as well as a model of HMS Beagle, the vessel which carried Darwin through South America from 1832-1835. The museum contained some other intriguing finds, such as claws and fur samples belonging to giant ground sloths, an ancient animal which fascinated the naturalist.

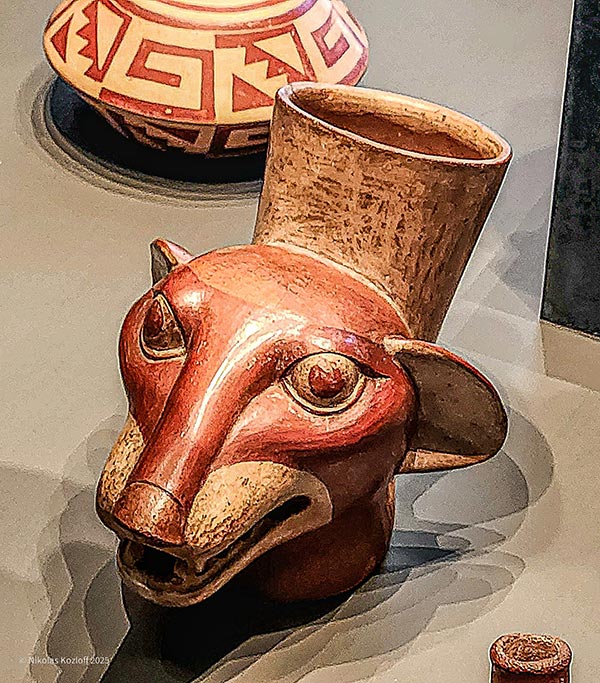

Then, I came across a curious sight: a display featuring indigenous peoples accompanied by the extinct Fuegian dog, which had been preserved for more than one hundred years. The specimen, which was scruffy and black with white tufts on its back, looked more like a lean fox or perhaps a small-built wolf. Beneath, a caption explained how the Fuegian dog accompanied indigenous peoples during hunting raids. For some time these ancient canids, which lived alongside Yagán and Selk’nam peoples, as well as the Aónikenk (or Tehuelche), have intrigued researchers. While the Fuegian dog —which is also confusingly referred to as the Yagán dog or Patagonian dog — is generally considered to be a domesticated form of the South American Culpeo fox (Lycalopex culpaeus), there is a degree of scientific debate regarding the animal’s precise origins.

Indeed, the story becomes more complicated in light of enigmatic museum specimens. Today, apart from the dog which I observed in Punta Arenas, there is only one other specimen housed at a museum in Argentina. When researchers examined both animals, however, they determined the Punta Arenas specimen was a dog, whereas the creature in Argentina was a fox, or at least displayed a high level of genetic similarity with Culpeo. The finding suggested hunter gatherers may have domesticated foxes in Patagonia, or at least succeeded in creating an “intermediate” dog halfway between a wild and domesticated creature.

But let us backtrack for a moment, and start at the beginning. Initial canids which made their way to South America descended from a North American ancestor which lived some four million years ago. Once they crossed the Panama corridor, the animals diversified and became genetically distinct. Though such canids weren’t true foxes, some of them came to resemble the latter physically through the process of convergent evolution. Despite their foxlike appearance, however, South American canids were more closely related to wolves and jackals. As they evolved, South American “foxes” developed their own unique adaptations to specific habitats, thus reinforcing Darwin’s musing about “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful.” In Chile, fossils belonging to Culpeo have been uncovered as far back as 2.5 million years ago.

Homo sapiens showed up on the continent much later, some 14,000 years ago. Indigenous peoples brought their own domesticated dogs with them, which had in turn evolved from wolves. Initially, the animals had difficulty adapting to the harsh tropical climate and disease, and it was only subsequently, once maize farming had been firmly established by 5,000 B.C., that dogs began to flourish in South America. Even so, it is thought that domestic dogs were primarily associated with sedentary societies in the Andes, and hunter gatherers in the Southern Cone did not adopt canids until later. While domestic dogs would have provided companionship, it also seems some indigenous peoples formed intimate bonds with other “foxes” which already lived on the continent. Indeed, foxes have been uncovered in Patagonian burial sites, where they were affectionately placed alongside human graves.

By 8,000 B.C., indigenous peoples spread to Tierra del Fuego or “Land of Fire,” an archipelago off the southernmost tip of South America and one of the last corners of the globe to be colonized by humans. Indigenous Yagán and Selk’nam peoples began to settle on Switzerland-sized Tierra del Fuego Island, with the former residing in coastal areas, and the latter spreading inland. It’s possible these colonizing canoers introduced some type of canid to the archipelago, but what sort?

Researchers argue there may have actually been two different species, that is to say the Patagonian dog used by the Selk’nam, which was a domesticated Culpeo, and the Fuegian dog used by the Yagán, which was descended from earlier North American dogs. Indigenous peoples may have brought both guanaco and canids to the archipelago to promote mutualism. Indeed, canids themselves were used to hunt guanacos, and provided warmth in shelters. Indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego, moreover, might have released hand-raised Culpeo foxes into the wild to provide future sources of pelts for clothing. The Yagán apparently valued canids, celebrating the animals within their own oral tradition.

Are we dealing, then, with essentially two separate canid species? The debate may still be out: in yet another wrinkle, researchers have determined that one ancient fox species similar to Culpeo, Dusicyon avus, may have been kept as a pet. The animal seems to have shared a similar diet to indigenous benefactors, suggesting the creature could have become domesticated (the word Dusicyon means “almost a dog”). The size of a German shepherd but less bulky, Dusicyon avus went extinct some five hundred years ago, though perhaps the creature lived on in isolated Tierra del Fuego amongst the Selk’nam into the twentieth century. It’s unclear what may have led to the creature’s demise, though perhaps it faced climatic pressures, competition from other dogs, or succumbed to disease.

It’s at this point that the story gets back to Darwin’s voyage and becomes truly remarkable. Prior to traveling to Punta Arenas, I sailed from Patagonia to the Falkland Islands, where I became intrigued by another extinct canid, the warrah (Dusicyon australis). During his stay in the remote South Atlantic archipelago, Darwin wondered how the animal, which resembled either a jackal or coyote, had wound up there. Based on genetic analysis, the warrah’s closest relative was Dusicyon avus, and diverged from the latter between 31,000 and 8,000 years ago (in 1876, the warrah was finally hunted to extinction by European settlers). Perhaps, in an echo of human colonization of Tierra del Fuego, indigenous Yagán brought the warrah to the Falklands in canoes.

Darwin’s encounter with the warrah would not be the last time he came across canids in South America. Sailing through Tierra del Fuego in 1833, the naturalist observed “savage” indigenous peoples and remarked the “quiet of the night is only interrupted by the heaving breathing of the men and…the occasional distant bark of a dog reminds one that the Fuegians may be prowling, close to the tents, ready for a fatal rush.” In Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin claimed disparagingly that indigenous people valued dogs more than old women, since the animals could catch otter as prey. Years later, the scientist suggested that Fuegian dogs could have developed such clever hunting skills through the process of natural selection. Writing in The Origin of Species, the scientist referred to his creature as a “semi-domestic dog.”

Some have suggested the Fuegian dog could have been a domesticated form of Dusicyon avus. Later nineteenth century accounts, in fact, refer to a fox in Patagonia resembling the warrah. Conrad Martens, an artist commissioned by Beagle captain Robert FitzRoy, drew a sketch of Tehuelche peoples in southern Patagonia accompanied by their “semi-tame foxes.” In yet another Martens sketch, we see the Beagle’s encampment on Navarino Island in Tierra del Fuego, with Yagán people flanked by smallish pet foxes. FitzRoy himself described dogs belonging to the “Canoe Indians” resembling “terriers, or rather a mixture of fox, shepherd’s dog, and terrier.”

Whatever the case, these dogs, or semi-tame foxes, would soon go extinct with the arrival of European settlers. After taking in exhibits at the Salesian Maggiorino Borgatello Museum in Punta Arenas, I sat down with director Salvatore Cirillo to gain more insight. In the nineteenth century, he told me, sheep farming was introduced in Tierra del Fuego. Once nomadic indigenous peoples sought to remove fencing linked to such farming, however, this resulted in violent reprisals from settlers. Cirillo added that indigenous people also suffered due to lack of immunity from newly introduced infectious diseases.

European settlers, backed up by the Argentine and Chilean governments, attempted to wipe out the Selk’nam and Yagán in a cruel genocidal campaign, resulting in a drastic decline of the indigenous population. Across town, I caught up with Lidia González, a Yagán indigenous woman who represented her people as a delegate to the Chilean constitutional convention held several years ago. Her mother, Cristina Calderón, was the last fluent Yagán speaker and passed away in 2022. González spoke to me about historic pain experienced by the Yagán, as well as enduring racism afflicting indigenous peoples to this day. Currently, she is learning the Yagán language herself, adding the community is doing its utmost to preserve other traditions such as basketry and canoe-making.

European settlers also wiped out indigenous people’s canid companions. Indeed, new arrivals viewed the creatures as a threat to cattle, and as part of the Selk’nam genocide, dogs were apparently hunted to extinction. Over time, indigenous canids were replaced by other domestic dogs introduced by European settlers in Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. The same could be said of the wider Americas, since the lineage of ancient dogs is almost non-existent today.

However, there’s a catch, since the Fuegian fox, or Lycalopex culpaeus lycoides, can still be found in the southern portion of Tierra del Fuego Island. Perhaps, some indigenous canids did not become fully extinct, but rather “regressed” from their tame form into being wild animals once more. Reportedly, there’s a close genetic similarity between Fuegian foxes and previous indigenous canids, which has led some researchers to suggest that “‘resurrection’ of the Patagonian or Fuegian ‘dog’ by means of retro-selection of ancestral characteristics seems a worthy enterprise.”

The genocide perpetrated against indigenous peoples resulted in dramatic environmental change on Tierra del Fuego Island, as Juan Francisco Pizarro, a government biologist in Punta Arenas, explained to me. Prior to European contact, Selk’nam were top apex hunters, since there were no other large animals which might compete for resources, such as pumas. Aided by their canid companions, indigenous peoples hunted guanaco, which constituted the main source of food.

However, once indigenous peoples and their pets were decimated, livestock farming took off, and conversely the guanaco population crashed due to such factors as habitat degradation and competition with sheep. It has only been over the past few decades, with the introduction of hunting restrictions, that guanaco numbers have recovered on the island. Should other “native” wildlife be re-introduced to Tierra del Fuego Island, I ask? It would be interesting, Pizarro remarked, to see if suitable DNA could be extracted from canid specimens, though attempting to resurrect such animals was a philosophically “complex” issue.

Amid all these unusual twists and turns, what can we learn about evolution from the experience of canids in South America? Curiously, Darwin himself failed to pick up on all the clues. A year after sojourning in Tierra del Fuego, the naturalist encountered Lycalopex fulvipes (or simply Darwin’s fox) while traveling within yet another Chilean archipelago to the north, Chiloé. However, Darwin did not scrutinize canids’ long history of “adaptive radiation” within South America.

Though the scientist failed to fully grasp this phenomenon, Darwin was fascinated by variations in dog breeds and behavior. Furthermore, the naturalist studied dogs’ adaptations to specific conditions. Darwin was particularly interested in hunting dogs, which informed his views on evolution. Take greyhounds, which serve as prime examples of adaptation and selection, since every bone and muscle were designed to run down hare.

Perhaps, if he had pursued the matter further, Darwin might have recognized similarities between South America’s “canid evolutionary laboratory” and modern-day dogs. Indeed, canids on the continent vary greatly in both physical appearance and diet, and these evolutionary changes occurred quite rapidly, since there were no large or medium-sized carnivores to compete with, and plenty of prey. That is to say, empty niches encouraged rapid radiation. This process is a “natural parallel to what we’ve done to dogs.”

Does our age-old “cross-species intimacy” with canids reflect something more profound about human nature? Darwin studied dogs’ emotional capacity, social behavior and affection towards people. In Descent of Man, the scientist used dogs as a means of illustrating the evolution of moral sense. Just as dogs were prone to pangs of conscience, so too did the same structure of feeling form the foundation of moral conduct in humans.

Darwin noticed that as animals became domesticated, they develop similar changes when contrasted with their wild ancestors. This phenomenon has come to be known as “domestic syndrome,” and is linked with tamer behavior as well as other physical changes such as shorter faces, smaller teeth and more fragile skeletons. Intriguingly, just like some animals, humans also display signs of domestication syndrome in comparison to our ancestors, suggesting a process of “self-domestication.”

Some experts believe such changes made us more social while developing complex language and culture. But how did we “self-domesticate”? One possible explanation is that social “beta males” started to cooperate to eliminate “alpha bullies,” or human ancestors developed a greater capacity for shared infant care. By pursuing group foraging, we would have become more social, cooperative and complex, while undergoing changes frequently observed in domesticated animals. It stands to reason, then, that if we study domestication syndrome in other creatures, this in turn might give us insights into our own human evolution.

For millennia, it might be argued, both humans and canids have domesticated each other. But should we necessarily regard this cycle as promoting progress? The story of indigenous peoples in Tierra del Fuego, as well as their canid companions, may provide a cautionary tale. While hunter gatherers tend to view animals as equals, settled people may regard such creatures as servants to be controlled. In this sense, “domestication doesn’t entail making wild animals tame,” but replacing “a relationship founded on trust with one ‘based on domination.’” This scenario starkly contrasts with Darwin’s more optimistic view of domestication, for when humans start treating animals as lower beings, it becomes much easier to treat fellow people in the same fashion.

Leave a comment