Ukraine: Reflections on the Maidan Revolution, a Voyage to Odessa, Donald Trump, Trans-Atlantic Disarray and Ironies of “Western Modernity”

Aghast at the rise of Donald Trump and the slow disintegration of the European Union, many Ukrainians may certainly wonder about the legacy of Maidan. Foremost in the minds of many revolutionaries who sought to topple the unpopular government of Viktor Yanukovych was the overarching need to bring Ukraine into line with supposedly western standards of modernity. Yet, if anything, recent developments have served to underscore that the West is hardly a paragon of modern, pluralistic and tolerant values. Indeed, as Ukrainians seek to make due on the promise of Maidan, they may ask themselves whether the West is worthy of political or social emulation at all.

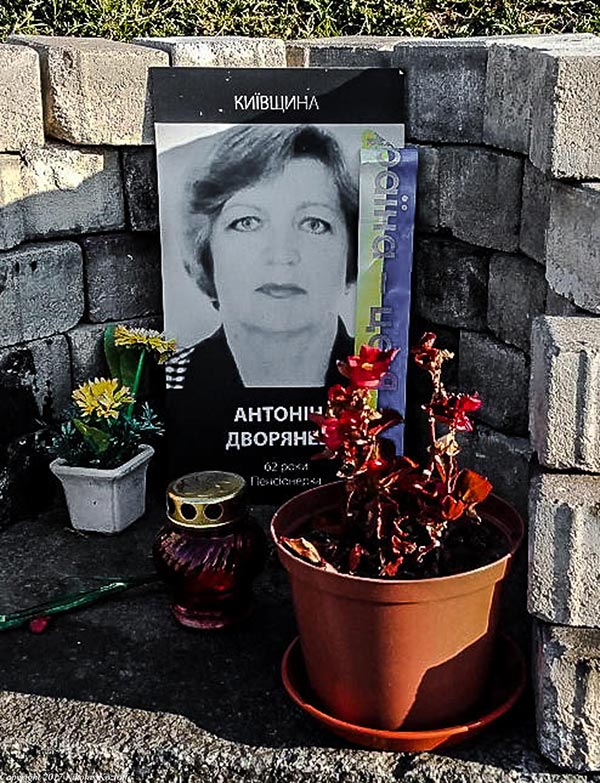

Such ironies were on vivid display recently, when I conducted my second research trip to Ukraine. The country is in the midst of Maidan’s third anniversary and during a ceremony in Kyiv, government officials, protest veterans and others placed flowers at a monument to the “Heavenly Hundred” martyrs who had been killed in clashes with the Yanukovych government. The celebration was marred by the ongoing escalating war in the east where Russian-backed separatists hold sway. Indeed, at one point demonstrators even ransacked a branch of a Russian bank. Hoping to soothe the nation and mollify fraying tempers, President Petro Poroshenko assured Ukrainians that Kyiv would never return to its Moscow-dominated past and was moving toward European modernity.

Bar Owner’s Optimism

For a more upbeat mood on Ukraine’s revolutionary legacy, I head to Bar Baraban, a café located just a few scant blocks from Maidan square. There, I speak with owner Gennady Kanishchenko, who harbored and protected students at his bar during the revolt against Yanukovych. Fleeing police brutality, students spent the night at his café at the very beginning of Maidan protest. Sipping tea at a table inside the bar, Kanishchenko remarks that he always wanted Ukraine to become “part of the civilized world” so as to guarantee a legitimate state of law and western freedoms. “Hopefully,” he adds, “outside pressure from the U.S. or E.U.” can help to eliminate corruption in Ukraine. Ultimately, Kanishchenko adds, Ukraine must become part of the European Union which in turn may help to protect his country from Russia.

There are indications that Kanishchenko’s optimism is somewhat warranted. Indeed, Maidan has spurred on the growth of civil society, including non-governmental organizations or N.G.O.’s. Meanwhile, the country has taken greater steps to ensure political and economic transparency. In line with reforms, officials must now reveal the true extent of their assets and property. Kyiv has also undertaken measures to ensure greater transparency in media, and not surprisingly reforms have revealed that media ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few fabulously wealthy oligarchs. Meanwhile, authorities are conducting police, judicial and tax reform.

Though the rise of Donald Trump has certainly scrambled expectations, one of the West’s key strengths is thought to be modern views on women’s rights. Just how has Maidan improved matters for gender equality? “Here in the bar,” notes Kanishchenko, “everything is respectful, but if you go out into the towns it’s more traditional and you get ‘rednecks.’ Despite rural conditions, Kanishchenko adds that women’s rights have steadily improved in Ukraine. Across town, former Maidan activist Nataliya Neshevets agrees. A coordinator at Kyiv’s Visual Culture Research Center or VCRC, young Neshevets remarks that feminism used to be pretty non-existent in Ukraine. To be sure, there were some small groups and perhaps a few dozen activists here or there but hardly what one might call a mainstream movement. On the Maidan, feminists were physically attacked “not so much by far right groups but by older people who were simply passing by, say men and women over the age of fifty.” On the third year anniversary of Maidan, however, “feminism is growing and maybe there’s more awareness about these issues now. The media is raising the issue of women. Four or five years ago feminism was stigmatized more but today public figures and writers are broaching the issue.” Neshevets adds, “I’m not sure if this was a result of Maidan, but maybe things started to snowball as a result of rebellion.”

Ukrainian Youth Speak

Despite these improvements, there are serious reasons to doubt that Ukraine is somehow on the cusp of becoming a “modern country.” So says Denis Pilash, another veteran of youth protest on the Maidan. I conduct my interview with Pilash in the lobby of Ukraina hotel, a retro, Soviet-era relic which hardly provides a modern backdrop. When I ask the activist to comment about the mood amongst his generation, the activist responds “I think that youth is more open, more liberal on social issues and more western than Russian youth.” On the other hand, he adds that surveys show that the vast majority of Ukrainians “are still very conservative as far as accepting people of different races or sexual orientation” (for a longer discussion of the mood amongst young students, see here).

Kyiv has staked its reputation on police reform, which is supposed to kick-start Ukraine’s supposed transformation toward modern, western values. Though Pilash is critical of many aspects of police reform, he concedes that authorities succeeded in providing adequate security during Kyiv’s most recent gay pride march. It was the first time that police had provided such security for the parade, which historically has been subject to street attacks and intimidation. Though there were fears the far right would stage attacks on parade participants, such concerns fortunately did not come to pass. Pilash suspects the police were acutely aware of public relations optics, since “the march was also attended by American diplomats and the police had to provide a good picture for the West.”

Despite this social progress, Pilash paints a rather bleak and decidedly anti-modern view of power relations in his country. Currently, the activist notes, Ukraine’s main investors hail mysteriously from tiny Cyprus or the Virgin Islands. “You know it’s got to be wealthy oligarchs like Dmytro Firtash or Rinat Akhmetov who are behind these investments in Ukraine and they get away with not paying any taxes here.” Kyiv should close all loopholes for offshore tax havens, Pilash remarks, while imposing progressive taxation. Unfortunately, the activist says, oligarchs are still in power even though Maidan displayed a strong anti-oligarchic bent. “We need to destroy the system of oligarchic capitalism once and for all,” Pilash declares.

Fiasco of Higher Education

Pilash isn’t the only youth activist who has become frustrated with the slow pace of reform. Yegor Stadny, another veteran of Maidan protest, is the Executive Director of CEDOS, a Kyiv think tank focusing on educational policy. To be sure, he says, there have been some improvements since the Yanukovych era, for example in the field of public procurements which are now conducted online in a more transparent fashion. In other respects too, such as the creation of a national anti-corruption bureau, Ukraine has made some strides. Unfortunately, Stadny says, “the speed of progress is glacial. I am fearful that at some point in future, the pace of change will decrease to such a degree that the clock will basically be turned back.”

Stadny is particularly riled about the pace of educational reform, which at first seems a bit ironic. On the surface at least, one of Maidan’s greatest accomplishments was the successful passage of a law on Higher Education Reform. In tandem with legislation, universities now enjoy academic autonomy to teach whatever they please, however Stadny declares that the same people who had previously stood against higher education reform now find themselves in charge within the government. As a result, “rectors have basically halted everything short of university autonomy because they aren’t interested in making systemic changes.”

To hear Stadny speak, one gets the impression that Ukrainian universities represent the very antithesis of what modern education ought to stand for. The majority of rectors, for example, are doing their utmost to head off a “proper competitive atmosphere and culture within the university.” Specifically, rectors seek to prevent open competition for job vacancies, be they teaching or administrative positions. Meanwhile, rectors appoint “compromised” staff to lead a national board on quality assurance, which is tasked with peer review. Stadny claims the rectors appoint people who are guilty of plagiarism “so they can be controlled.” Faced with such daunting odds at university, as well as an unenviable job market, Ukrainian youth is feeling discouraged. Stadny tells me that more and more students are pursuing their studies abroad, and this represents a key “brain drain” for Ukraine.

As the advance guard of Maidan’s reformist N.G.O. impulse, Stadny meets constantly with government ministers and staff. Officials tend to agree with his group’s proposals on secondary and higher education reform, he says, but then they quickly change tack by claiming that “now isn’t the proper time,” or “the path you’re advocating is too radical.” Speaking candidly, Stadny remarks that he’s frequently very close to simply blurting out “this is bullshit!” and standing up in the middle of meetings. “Look,” the Maidan activist adds, “we paid the highest possible price during the revolt against Yanukovych when peopled died for their beliefs, and you are saying ‘this reform is too radical’? This is completely insane!”

Odessa and the Duke de Richelieu

Having concluded my interviews in Kyiv, I head south to the Black Sea port of Odessa in the hope of getting a fuller picture of Ukraine’s western ambitions. Historically, Odessa has always prized itself on being modern, tolerant, multi-ethnic and cosmopolitan. Throughout its history, Jews have played an important role in the cultural fabric of the city. Upon arrival, I pay a visit to Odessa’s local archaeological museum where patrons are greeted with relics and statues from the city’s ancient history of Greek colonization and settlement.

While walking around Odessa itself I am struck by the city’s ornate neo-classical and over the top Moorish Venetian architecture dating back to Czarist times. And yet, the city’s Black Sea boardwalk is desolate and abandoned. Having languished since the Belle Epoque, Odessa has a rather dilapidated air about it. If I were to collect bricks or materials from most any house in Odessa, I wonder, would they simply crumble into dust while lying in my hands?

Hoping to pierce the veil on Odessa’s modern aspirations and mystique, I head across town to the city’s old Jewish quarter. There, I speak with Sergei Ischenko, a local journalist and former Maidan political activist on the independent leftist circuit. When the revolt against Yanukovych erupted, Ischenko says, some activists went to Kyiv while others congregated on Odessa’s Primorsky Boulevard, near the monument to Duke Emmanuel Armand de Richelieu, one of the city’s founders.

Maidan protesters’ psychological link to Richelieu is significant, since the nobleman is a prominent symbol of European Odessa. A kind of honorary foreigner, Richelieu was granted the rank of lieutenant colonel by Czarist authorities in 1795. Sometime later, he was made governor of Odessa, at which point the Duke promptly set about transforming the small village into a proper city. In tandem with his modern sensibilities, Richelieu cleaned up corruption, built port facilities, constructed a theater and encouraged trade.

Odessa and Maidan

In the wake of Maidan, will Odessa live up to its western heritage of modernity and the Duke de Richelieu? “There are two Odessas,” Ischenko tells me as we chat in his apartment. “On the one hand, you have anti-Semitic pogroms against the Jews during the Czarist period, and on the other hand you have a more progressive and tolerant sensibility. It’s a problem, however, because many people don’t understand why tolerance is good and xenophobia is bad. Even amongst the more intellectual and educated set, there are xenophobic elements.” Ischenko adds that anti-Semitism still exists, though it’s slightly “under the radar” and isn’t expressed publicly.

To hear the journalist speak, Odessa is a bundle of contradictions. The younger generation tends to be more multi-cultural and western, whereas older folk are more pro-Russian, right wing, xenophobic and religious. The latter may even admire the Czars as well as Stalin, while seeing little contradiction in such views since “this is entirely normal in Odessa.” Maidan however has served to moderate extremist ideas, and “ethnic-based nationalism isn’t popular, even within radical far right groups. Even some racist soccer hooligans now say that ‘Crimean Tatars aren’t all that bad, or the Jews aren’t all that bad.’”

Meanwhile, Maidan has made some ethnic minorities more patriotic and could help integrate marginalized groups into wider society. Bizarrely, some ethnic minorities belong to right wing political groups in Odessa. “I know of one guy who is a Russian Jew,” Ischenko says, “yet he is a member of Right Sektor. I also know an Asian person who was a member of a rightist group. That’s Odessa!”

Reliable Holland Wavers

Despite the many contradictions, Ukraine still yearns for Western-style modernity. In a recent poll, 49% of Ukrainians favored E.U. integration while only 16% supported joining a Russian-led customs union. Yet three years on, veterans of Maidan protest are wondering whether the European Union is still interested in signing their country up for membership. Indeed, Kyiv’s bid to sign an association agreement with the European Union, which was the initial spark which set off the Maidan revolution in the first place, has stalled.

The slow disintegration of the E.U. has not helped to assuage Ukrainian concerns. The departure of Britain from the E.U. via “Brexit” vote removed one of the West’s foremost critics of Russian aggression. Amidst this crisis of confidence, Holland then added to Ukraine’s woes by voting against Kyiv’s E.U. bid via non-binding referendum. The Dutch referendum could block visa liberalization for Ukrainians interested in traveling to other E.U. nations. As a result of the electoral upset in Holland, Prime Minister Mark Rutte is legally bound to “reconsider” the entire agreement. Rutte is no doubt concerned about the rise of Geert Wilders, who has been hailed as the “Dutch Donald Trump,” and the latter’s anti-immigrant and Euroskeptic Party for Freedom. Now under pressure from rising right wing populism, Rutte has floated the idea of amending the E.U.-Ukraine association agreement with European officials so as to incorporate voters’ input.

Ukraine may wonder whether Western Europe is vacillating. If Holland, the so-called bastion of modern values and tolerance, can no longer be considered a staunch ally then who can Kyiv actually trust? The Dutch vote is all the more ironic in light of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down over Ukrainian territory by Russian separatists in July, 2014. Since two thirds of the passengers were Dutch, one might think The Hague would be more interested in embracing and protecting Ukraine from Russia, rather than running away from an E.U. association agreement.

Fraying Diplomatic and Military Ties

Lack of crucial diplomatic support from western quarters is profoundly dispiriting to many in Ukraine. Oleksandra Matviychuk, a coordinator of the Euromaidan SOS, a human rights initiative, recently expressed her frustrations. Speaking with Euro Maidan Press, she remarked, “From the point of view of ordinary Ukrainians, this is a betrayal behavior of the European Union. Ukrainians are probably the only people who died under E.U. flags for E.U. values. As a country, we fulfilled all the requirements for a free visa regime with the E.U., but this question is still on the agenda.” Matviychuk adds, “Russia understands clearly that if Ukraine will be able to conduct democratic transformations, it will have an irreversible influence on the whole region. In particular, on post-Soviet countries, especially Russia, where freedom slowly narrows down to the level of the jail cell.”

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) writes that even though Ukrainian public opinion still favors the E.U., morale has suffered. “The image of an E.U. racked by crises and too preoccupied to care about Ukraine is chipping away at this plurality,” the group remarks, “as seen by the growing popularity of the ‘Eurorealism’ trope (as in, ‘Let’s be realistic, our prospects are not good’).” With the West fracturing, there are indications that elite opinion in Ukraine might also be splintering. In a recent Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal, wealthy oligarch Viktor Pinchuk remarked that Ukraine should give up on Crimea and withdraw its bid to join NATO and the E.U.

In exchange for such concessions, Pinchuk believes Kyiv could secure a successful peace deal in the east. Fellow oligarch Dmytro Firtash reportedly agrees with Pinchuk and seeks to revive trade with Russia. ECFR remarks, “Both men have a personal interest in their companies regaining access to Russian markets. But the campaign also anticipates and feeds a Trumpist agenda, when Ukrainians are profoundly split about how to approach his presidency after Trump’s string of pro-Russian comments.”

Meanwhile, as if these concerns weren’t serious enough, Kyiv fears the newly-inaugurated Trump administration will betray Ukraine by “pushing for some kind of Yalta 2.0 agreement with Russia.” Ukraine cannot defend itself alone, and given Trump’s hostility toward NATO it seems unlikely the latter will expand its security umbrella toward Kyiv any time soon. Given such stark realities, Ukraine may seek more unusual defense arrangements with other Eastern European nations. Take, for example, Kiev’s rapprochement with the so-called “Visegrad Group” comprising Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. With relations deteriorating with Russia as of late, the political and military bloc has been holding meetings about the situation in Ukraine. Though Kyiv has had its own stormy historic relations with Poland, the latter has been sounding increasingly eager to come to the defense of its eastern neighbor.

Sobering Choices

Back in Kyiv, I touch on the many ironies of Ukraine’s situation with pro-Western bar owner Kanishchenko. Despite internal pressures within the E.U., he insists that “Europe and NATO are the only escape for Ukraine. We need to be backed up by someone in our relations with Russia.” ECFR notes, however, that if Ukraine wants to get into the good graces of the E.U., the country “will need to get serious about tackling corruption and advertise some big reform success stories in the coming year.” ECFR adds, “This may not be the top item on Trump’s agenda, but European public opinion cares more about whether Ukraine is worth saving; and Kyiv needs to do much more to make a convincing case in this respect.”

Whether Ukraine can muster the effort to follow through on Maidan’s reformist impulse, however, remains to be seen. Irish Times notes that Maidan’s third anniversary has been marred by widespread disillusionment as Ukrainians grapple with government failure to eliminate corruption, eviscerate the oligarchs or improve the economy while simultaneously addressing wealth inequality. President Poroshenko, meanwhile, finds himself surrounded by the pro-Russian Opposition bloc party on the one hand and far right Ukrainian nationalists on the other.

Back in Bar Baraban, Kanishchenko remarks wistfully, “Everyone was thinking that we would become Europe immediately but it takes time and our country was never exposed to the West.” When I ask the bar owner whether Ukraine is living up to Maidan’s aspirations to create a more multi-ethnic and tolerant society, he muses “Yes. But I think this tolerance in the West, which used to be one of the features of society, is now changing.”

Leave a comment