A History of Vandalism: Welcome to Ukraine’s Historic Holocaust Site

While many Ukrainian politicians and political activists alike have embraced pointed views on their country’s thorny and controversial World War II past, relatively few may claim direct personal experience of the Holocaust. Abraham Kristein, however, is the rare exception of someone who not only witnessed horrific wartime atrocities in Soviet Ukraine but also lived to tell the tale. Now 84 years old, he soberly recounts his harrowing story over lunch at a local synagogue located in Podil, Kyiv’s old Jewish historic quarter.

In the summer of 1941, when German forces invaded his home town of Tulchin, Kristein was just a small boy in first grade. The Nazis promptly organized a ghetto in the western Ukrainian town, and Jewish families were subjected to great restrictions on daily life. Several months later, in the midst of freezing winter, the Germans went even further by closing the ghetto outright. Kristein’s Jewish family, along with many others, was crammed into a local school where they were forced to stand for days on end.

Without any food or water, it wasn’t long before exhausted victims started to perish. But Kristein’s misfortunes had only just begun, as the Germans forced survivors to march through Tulchin in the cold. At one point, the crowd was obliged to cross a freezing river, and Kristein’s father took him in his arms as the two plunged headstrong into the water. Later the grim march continued, with Kristein’s mother desperately trying to secure food from a neighboring village. In response, the Germans beat her.

At long last, the crowd reached the Pechera concentration camp where inmates were similarly deprived of food. Kristein vividly remembers how little children literally licked icy windows, which was the only source of water. Kristein’s father tried to gather the entire family and find the best place to stay on the premises, but everyone was stacked up closely and it wasn’t long before more Jews began to die. During the first two brutal weeks at Pechera, Kristein witnessed the death of his sister, as well as a cousin and an aunt. Now at wits end, Kristein’s father and brother escaped the camp at night and managed to trade in their clothing for food. But when the camp’s Ukrainian guards found out what the family patriarch had done, they beat him so badly that the man later died of his injuries.

Babi Yar and Collaboration

Though Kristein’s poignant story unfolded more than seventy years ago, the events themselves carry key political significance in present day Ukraine, a country which is seeking to come to terms with some of the more sordid details of its wartime past. Recently, Kyiv authorities held the 75th commemoration of the Babi Yar (or in Ukrainian, Babyn Yar), massacre. It was the Germans, not Ukrainians, who orchestrated the Holocaust here. To their credit, many Ukrainians helped shelter and protect local Jews. What is more, like the Jews millions of Ukrainians suffered immeasurably under German occupation and valiantly fought the Nazis while serving in the Soviet Red Army.

Nevertheless, it is also true that locals like the guards at Pechera assisted the Nazis in committing atrocities. Perhaps the most controversial and notorious case of such collaboration occurred at Babi Yar, a ravine located on the outskirts of Kyiv. There, German police and the SS killed 33,771 Jewish men, women and children in just two days at around the same time that Kyrnstein and his family were struggling to survive at Pechera.

What makes this episode so politically explosive is that local collaborators assisted the Germans. Prior to the massacre, Ukrainian Auxiliary Police distributed an announcement to the Jews of Kyiv, ordering the latter to assemble at a specific intersection within the city. Later, Ukrainian policemen patrolled the gates at a local Jewish cemetery, which in reality served as a point of no return leading on to Babi Yar. According to historians, the Jews were herded into enclosed areas marked by barbed wire at the ravine, where they were guarded by Ukrainian collaborators. Later, Jews were stripped naked, beaten, forced to lie on the ground and machine-gunned while face down. The dead and wounded alike were covered with dirt and rock.

Babi Yar turned out to be the single largest mass murder of Soviet Jews during World War II, and served as a future Nazi template for industrial-scale mass murder. Over the next two years, the Nazis shot thousands more Jews at Babi Yar in a similar fashion, as well as others including Roma, communists, Ukrainian nationalists and Soviet prisoners of war. In total, more than 100,000 people were murdered at the site during the Nazi occupation of Kyiv.

Holocaust Survivor Reflects

Remarkably, considering all that he has been through, Kristein doesn’t seem particularly bitter. Speaking to me at the Podil synagogue, he reflects on his own story as well as Babi Yar’s lasting legacy. When Jewish inmates at Pechera became desperate over living conditions at the camp, they literally lit the place on fire. At that point, Kristein’s mother urged him to escape. Fortunately, the young boy managed to do just that: wandering around the forest, he met up with partisan fighters. Eventually, a local woman wound up taking care of Kristein. In 1943, the Soviet army beat back the Nazis and Kristein and his mother, who had languished at Pechera in extremely poor health, were both liberated. They were the only two members of the family to survive the conflict.

Impressively, Kristein managed to get his life back on track after the war. Returning to his native town of Tulchin, he acquired a decent education and in 1954 moved to Kyiv where he became a successful rocket engineer working in the Soviet arms industry. In order to secure employment, however, Kristein was obliged to fill out some forms. At one point, he was asked what he had been doing during the war. When he answered that he was interned at Pechera, the authorities perversely asked him to prove it by submitting documentation. Befuddled, Kristein declared that he lacked any such documents. The entire episode, Kristein tells me, was reflective of typical Soviet thinking predicated on erasing the historical memory of Jewish suffering. In fact, Kristein continues, the authorities were so determined to erase Pechera that in truly Orwellian fashion they literally claimed the camp had never existed.

Kristein’s experience is unsurprising in light of overall Soviet attitudes toward the Jews. Kyiv Jews, for example, were prohibited from practicing their faith. In the post-war period, Moscow ignored the genocidal nature of Germany’s extermination of the Jews, while officially labeling Nazi victims as either “Soviet citizens” or “civilians.” Not stopping there, the Soviets deliberately covered up Nazi crimes on Ukrainian soil. It didn’t help matters, Kristein adds, that some Nazi collaborators and their children were still around and reluctant to address sensitive topics from the past. In line with official policy, the authorities downplayed the fact that the majority of people who had died at Babi Yar were Jewish, preferring instead to refer to victims as “peaceful Soviet citizens.”

Somewhat audaciously, Kristein and his Jewish friends challenged the authorities in the 1950s by seeking to commemorate Babi Yar every year on September 28th and 29th. When they showed up at the ravine, however, the police would chase the contingent away. Those who resisted were beaten and taken into police custody. It wasn’t until 1976 that the Soviets finally erected a memorial at Babi Yar, and even then the monument simply honored the “citizens of Kyiv” who had been killed at the ravine.

The Commemoration

How much progress has Ukraine made on Babi Yar since the country gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991? As part of the press corps flown in to Kiev to attend the commemoration, I was impressed with the array of activities organized around the event itself, from film screenings to theater productions to presentations provided by Holocaust historians to musical performances to lectures to ceremonial speeches to an official state ceremony.

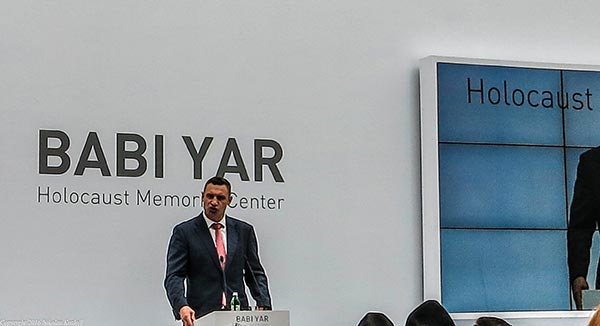

At Taras Shevchenko National Museum, I attended a so-called “ceremonial signing” of the Declaration of Intent to create a memorial center at Babi Yar by 2021, which is designed to honor victims at the ravine. President Poroshenko attended the event, along with other officials including Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko as well as German Khan and Victor Pinchuk, two wealthy philanthropists who are helping to fund the memorial.

Then, the government held a separate ceremony at the Babi Yar site, which was attended by foreign dignitaries as well as Poroshenko himself. To his credit, the president sought to come to terms with mass murder, remarking that “the lesson of Babi Yar is a reminder of the frightening price of political and moral nearsightedness.” In a further effort to turn the page, Poroshenko declared “there have been those [in Ukraine] for which one felt shame. And this, too, cannot be erased from our collective memory…No Ukrainian has the right to forget this tragedy.”

Poroshenko should be praised for his comments, yet it would be difficult to miss the not so subtle political backdrop to the Babi Yar commemoration. Indeed, during the ceremony held at Babi Yar, Poroshenko touched on the lessons of the Holocaust while simultaneously mentioning his country’s conflict with Russia over the latter’s annexation of Crimea, not to mention Kremlin backing of the secessionist war in the Ukraine’s east. In light of ongoing military conflicts, not to mention Kyiv’s dire economic straits, Ukraine has a vested interest in securing vital political and diplomatic support from western European nations and demonstrating that it is a modern and tolerant society.

However, Ukraine’s constant military troubles with Russia have encouraged the rise of right wing nationalism, and in particular certain groups which support the government while displaying a record of collaboration with the Nazis and support for fascism. Needless to say, Putin has sought to take full advantage of such backward developments and accuses Ukraine of harboring “fascists,” and anti-Semites. In addition, when Putin annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, the Russian president declared such moves were necessary so as to protect minorities from anti-Semitic fascists behind the Maidan revolution which had earlier toppled his political ally, Viktor Yanukovych.

A History of Vandalism

In the midst of the escalating war of words and high stakes public relations, Babi Yar has assumed key symbolic importance. When the site was repeatedly vandalized, former Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk claimed the attacks represented a deliberate political provocation against his government. There are “compelling evidences [sic]” Yatsenyuk remarked, that “we are facing well-planned and thoroughly prepared provocations” whose purpose is to “throw discredit upon Ukrainian authorities and to destabilize the internal political situation in Ukraine.”

Repeated attacks against Babi Yar have severely embarrassed the Poroshenko government: in 2015 the site was vandalized a whopping six times. Swastikas, for example, have been spray painted over the Babi Yar menorah. In one incident, a group of individuals burned an Israeli flag at the menorah on National Holocaust Remembrance Day which is observed on January 27th. And in another disturbing development coinciding with Rosh Hashana, assailants placed tires around the menorah, poured inflammatory liquid on to the statue and then set it alight. Ukrainian Jews believe the fire could have melted the menorah if the fire had not been extinguished.

Just who is responsible for the acts of vandalism remains something of a mystery. Josef Zissels, General Council Chairman of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress in Kyiv, believes the vandalism could have been carried out by insidious pro-Russian elements in an attempt to discredit Ukraine. Other Jewish leaders are less sure of who might be behind the incidents at Babi Yar, or what the attackers’ motivations might be. What is clear is that authorities haven’t done a very good job of catching the perpetrators, despite claims by Mayor Klitschko that he would improve local security. Indeed, Jewish leaders have criticized officials for failing to provide adequate police presence, and some complained that “[The] almost no reaction of civil society and mass media, no feedback from authorities and law enforcement agencies in respect to the events in Babi Yar clearly indicates ignorance of the society in respect to the large scale tragedy that happened to the Jews of Ukraine during the Holocaust.”

“Babi Yar spans a large area,” Zissels told me in Kyiv during an interview. “It’s difficult to observe what’s happening there and not so easy to protect.” Nevertheless, Zissels reports that he and his organization paid a private security firm to monitor Babi Yar and even provided the authorities with several cameras. At one point, the cameras caught young hoods in the midst of vandalizing the site, but unfortunately the cops took forty minutes to show up and ultimately failed to make any arrests. On another occasion, the police confessed they were unable to provide adequate protection because they simply lacked the logistical means to do so.

“Obviously,” Zissels remarks, “Babi Yar will be safe around the time of the commemoration due to the large presence of foreign politicians, dignitaries and delegations. The trick is what will happen next month once everyone leaves and we get the same problem all over again.” Back in Podil, when I ask Kristein if he shares Jewish leaders’ concerns, the Holocaust survivor declares, “Well, the cops are on the side of the vandals.”

Ukraine’s Mass Graves

Sitting across from Kristein at Podil’s synagogue is Leonid Iosipovich Podlesny, an independent researcher who seeks to mark and identify Ukraine’s many mass graves of the Nazi era. It’s no small task, given the magnitude of historic crimes. Indeed, historians estimate that almost a million Jews were killed in Ukraine during World War II. Indignantly speaking to a small crowd at the congregation, Podlesny recounts how local Ukrainian police failed to assist him in his work. Podlesny is not alone: Jewish leaders have accused the government of not only failing to protect Babi Yar, but also other Holocaust sites around the country.

Kirill Danilchenko, Josef Zissel’s assistant at the Euro-Asian Congress, is hardly surprised by such developments. The police are lazy, he says, or perhaps even wary of outsiders coming to their towns and “poking around.” “What if investigators start making accusations, creating disorder and so on?” Danilchenko asks rhetorically. “Maybe people are still around who know about these events, or their parents had something to do with atrocities. Perhaps there was some collaboration, so it’s easier for them to just put on a poker face and ignore investigators.” The only way the situation will change, Danilchenko adds, is if the police get a “kick in the pants” from high up authorities, because otherwise they will “try to do as little as possible.”

Across town near Maidan square, I catch up with Eduard Dolinsky, Director General of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee. There are more than two thousand Jewish mass grave sites throughout Ukraine, he tells me. Recently, a historic Holocaust site was vandalized near the town of Lubny in Poltava province. Four thousand Jews were killed there during World War II, and recently American school children raised money to commemorate the site. Later, the funds were used to plant eight million sequoia trees near a local monument. But according to Dolinsky, the monument was painted over and covered with swastikas. While certainly appalling, the Jewish expert declares that such incidents occur virtually every day. Indeed, while anti-Semitic violence in Ukraine is lower than Western European countries, vandalism has alarmed the local Jewish community.

Historical Amnesia

Yet another problem, Dolinsky adds, is that some Jewish massacre sites are well known but unmarked. “I’ll give you a specific example,” he remarks. “I come from the town of Lutsk in western Ukraine. At the time of the German advance, the town was 70% Jewish. There is a massive Holocaust grave of 25,000 Jews who were killed there. However, the monument is small and only occupies a small portion of the original mass grave area. The monument is located inside a sugar factory, and this is considered to be a memorial. Within other areas of the site, people grow vegetables on private gardens.” As it turns out, the case of Lutsk is hardly unique. In Kovel, a city located in northwestern Ukraine, local authorities authorized a traveling zoo to set up shop on top of a mass grave of thousands of Jewish Holocaust victims. Dolinsky says he doesn’t know if Kovel was a case of “[idiocy], criminality, cynicism, apathy — or maybe all of the above.”

Back at Babi Yar, there’s a similar sense of unreality. If one did not actively search for markers at the ravine site, one might be oblivious to what had actually happened here. Walking around the area, I spot people walking their dogs around various memorials. The menorah site, meanwhile, is built around a construction waste dump. Spread out over a large area, the various Babi Yar memorials honoring Jews, Roma and others are difficult to spot. Indeed, many locals don’t even know why various monuments have been erected at Babi Yar, including a Soviet-era behemoth showing people buried on top of one another, and a group of dolls with broken heads which is supposed to represent child victims. Such glaring deficiencies may contribute to overall historical amnesia, since Jews number only about 100,000 in Kyiv today out of a total population of 2.8 million, and Yiddish is almost never heard on city streets. Quite rightly, local Jews call the current status quo at Babi Yar a national disgrace.

To their credit, local and national politicians have sought to rectify the deplorable state of affairs. For instance, Poroshenko has announced plans to build a multi-million dollar Holocaust museum honoring victims of Babi Yar. In a separate initiative sponsored by a Canadian organization called Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, an architectural competition has been launched to transform the park into “a space of reflection and acknowledgement of the extreme inhumanity and tragic events” and where they took place. The museum will include a research institute, a “memory square,” an educational center and a wall of sculptures depicting Jewish victims.

Back in Podil, Kristein reflects on the commemoration at Babi Yar. To be sure, he remarks, Ukraine has made great strides since gaining independence in 1991 and the country is definitely less anti-Semitic than before. In particular, Kristein was impressed when he heard Poroshenko discussing the controversy surrounding Ukrainian collaboration at Babi Yar. Nevertheless, he believes that anti-Semitism is still deeply rooted in Ukrainian society. Up until fairly recently, he says, it was not uncommon to overhear ugly anti-Semitic comments in daily life. Traveling near Babi Yar on a bus some twenty years ago, the Holocaust survivor overheard a young man remark flippantly, “Oh, is this the famous place where Hitler failed to polish off the Jews? Too bad.” A woman on the bus started to cry and declared, “Half my family died at this place.”

Will the younger generation become aware that Jews and others were once neighbors? Will authorities display the necessary political will to foster a more tolerant society? During recent commemorative events, it certainly seemed as if independent Ukraine had turned a critical page. Time will tell, however, whether Kyiv is willing to come to terms with its historical demons.

Update: during a 2018 visit to Kyiv, I had the interesting and valuable opportunity to attend the premiere screening of a documentary film entitled The Road to Babi Yar.

I was at Babi Bar 4 years ago, and saw the first ravine which is back at the end of a small trail, the entrance of which had small memorials from various groups to groups that were mass murdered there and thrown into this wooded ravine, very steep. Then I went to the large area where ravines were dug to receive the murdered bodies. Here in a park like setting it is very large and grassy and peaceful but shows the vast extent of the numbers that were killed. In the middle is a massive group statue of jews intwined showing the horror on their faces, the assembly reaching skyward. Where is there a picture of that monument which is the most memorable and visually literal to describe the horror of the massacre??????? You should include pictures of that huge monument in your Photography of Babi Yar. P.S. I am an American Presbyterian and more enlightened about the Holocaust in Ukraine after my visit.

I have photos of that statue, but it is utterly hideous in my view so I didn’t include those images. — NK